Question: I’ve heard that professional athletes get “Platelet Rich Plasma” injections to speed up healing after sports injuries. I have a bad knee from arthritis. Could these injections ease my pain and help me avoid knee-replacement surgery?

Answer: Platelet Rich Plasma – or PRP – can provide pain relief to some patients. But it’s not a permanent fix. Nor is it covered by public or private health insurance. So, if you’re interested in trying PRP, you’ll be reaching deep into your own pocket. The cost of an injection varies from $300 to $600.

Despite these shortcomings, the therapy – which is promoted for conditions ranging from joint pain to hair loss – is growing in popularity. The global market for PRP is estimated at $400-million a year, says Dr. Moin Khan, an orthopaedic surgeon and assistant professor at McMaster University in Hamilton.

It’s often touted as a “natural” therapy that harnesses the patient’s own healing powers.

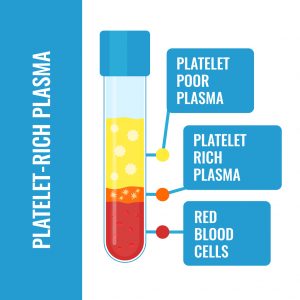

For the procedure, some blood is drawn from the patient and put into a centrifuge. The machine spins the blood, separating it into different parts.

Platelets, growth factors and other blood components involved in tissue repair are collected together to produce the PRP. This concentrated mixture is then injected directly into the part of the body needing treatment, such as a sore joint.

Numerous studies have examined the use of PRP in patients with knee osteoarthritis, in which the cartilage providing cushioning between bones shows signs of wear.

Some studies suggest PRP is superior to other injectable treatments such as hyaluronic acid (HA) and cortisone.

In particular, PRP may result in up to a year of relief, compared to six months for HA and several weeks for cortisone.

However, other studies fail to demonstrate that PRP delivers such a lengthy benefit and indicate its duration is similar to HA.

One key weakness with this research is that not all PRP products are the same, says Dr. Khan. “There are more than 40 different commercial PRP systems available and each one differs in its concentration of platelets and growth factors,” he explains.

To further complicate matters, the treatment protocol has not been standardized. A doctor may give a patient either one, two or three injections over a period of weeks.

“We don’t have good research to show the best type of PRP or the best number of injections,” adds Dr. Khan.

It’s also important for patients to realize that PRP doesn’t actually repair damaged joints.

“It won’t make the cartilage grow back,” says Dr. Tim Dwyer, an orthopaedic surgeon and assistant professor at the University of Toronto.

Instead, it appears to simply reduce inflammation which, in turn, helps to temporarily ease pain and increase joint flexibility.

When the anti-inflammatory effects wear off, some patients opt for more PRP injections, says Dr. Dwyer.

“It doesn’t work for everyone,” he cautions. PRP seems to be most effective in patients with mild to moderate osteoarthritis. “The worse your arthritis, the more likely it is not to be of benefit,” says Dr. Dwyer.

In the early stages of osteoarthritis, exercise and other conservative measures should be tried before invasive treatments, says Dr. Sebastian Tomescu, an orthopaedic surgeon at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto.

Exercises that target specific leg muscles can help stabilize joints. “The stronger your legs, the better your knees will feel,” explains Dr. Tomescu.

Some doctors are concerned that patients are jumping to PRP injections without first attempting basic exercises.

And they’re equally concerned that PRP is being promoted for conditions where there’s little or no evidence that it provides meaningful results.

Indeed, reports of celebrities such as the Kardashians getting “vampire” cosmetic facials and treating hair loss with PRP may be fuelling unrealistic public expectations.

“People are spending a lot of money on it and there are really no good studies to show it works on all these conditions,” says Dr. Khan.

More research is clearly needed. But, in the meantime, it’s not easy for patients to make informed decisions about PRP. So, probably the best thing to do is start with what we know has some benefit – exercise.

One evidence-based knee and hip exercise program worth considering is called GLA:D (Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark) which was developed by Danish researchers. You can find more information online at gladcanada.ca

Sunnybrook’s Patient Navigation Advisor provides advice and answers questions from patients and their families. This article was originally published on Sunnybrook’s Your Health Matters, and it is reprinted on Healthy Debate with permission. Follow Paul on Twitter @epaultaylor.

If you have a question about your doctor, hospital or how to navigate the health care system, email AskPaul@Sunnybrook.ca

The comments section is closed.

Thank You for your information. I have arthritic knee with “moderate loss” and had first ACP in 2016 which lasted pretty much without pain for 3.5 yrs. Now 9 of 2020 I started with severe pain and Dr’s xrays showed nearly TOTAL loss in Medial. I was shocked as I thought that the ACP had been doing more than just easing pain. I had NOT been explained to me that the bone and cartilage would continue to deteriorate. Dr at fault for that! Patients should be better informed!

Now facing Partial or possibly total replacement, but first I had another ACP ($600.! again)

Here’s hoping I get a little more time to find another OR Surgeon!