As the current COVID-19 pandemic wave abates and we prepare to relax public health measures in many provinces, it is easy to forget how close we came to overwhelming our health-care systems barely a month ago.

As in previous waves, preparations were underway for the possibility of ICU triage – having to decide which patients requiring critical care would receive it and which would not – with some suggesting that this measure of last resort would have been necessary in Ontario had it exceeded 900 patients with COVID-19 in ICUs. In fact, the number of Ontario ICU patients with COVID-19 became uncomfortably close to this precipice, peaking at 891 on May 1. While Ontarians may thank our public health measures for helping us avoid this grim eventuality – and we absolutely should – we should also recognize that a recommendation by the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) in early March 2021 to delay second vaccine doses played a very important role as well.

By early March, COVID-19 infections had partially subsided but many of Canada’s hospitals were still surging beyond capacity. Modelling was also showing that the COVID-19 variants of concern were likely to create a wave of new infections that would dwarf previous surges. To make matters worse, expected vaccine deliveries were delayed and smaller than anticipated. Many individuals at high risk of death or serious illness had already received one dose but there was not enough vaccine to provide second doses within the 3-4-week period supported by clinical trial data while also continuing to vaccinate other high-risk individuals before another wave hit.

NACI’s recommendation was based on a plausible hypothesis: in the context of vaccine scarcity, delaying second doses and getting first doses into more arms earlier would result in greater population-level protection. Quebec had already taken this decision in early January in response to anticipated delays in vaccine delivery.

How big of a difference did that make in Ontario? It is hard to say with certainty but if we focus on the period between March 1, when the recommendation was made, and the beginning of May, when ICU occupancy peaked, then the difference appears substantial.

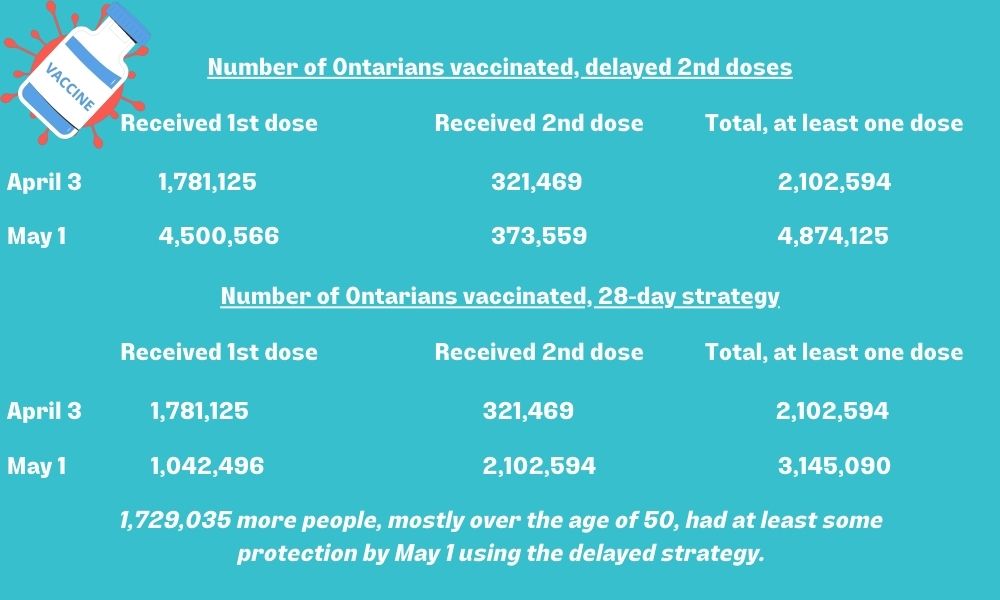

- By May 1, Ontario had administered 5,247,684 vaccine doses: 4,500,566 people had received their first dose while 373,559 had received two doses. This means that a total of 4,874,125 Ontarians had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. If we had continued to provide second doses 28 days following the first, we can assume everyone who had received a vaccine prior to April 3 (28 days prior to May 1) would have received two doses by May 1. Everyone who had received a first dose after April 3 would, by May 1, still be on their first dose.

- By April 3, Ontario had administered 2,424,063 vaccine doses, with 321,469 people having received two doses. This means that a total of 1,781,125 people had at this point only received their first dose, and by May 1, following the 28-day interval, would be receiving their second dose.

If we had continued to administer second doses at the 28-day interval, by May 1, 2,102,594 people would have received two doses (a total of 4,205,188 doses administered), and 1,042,496 just one dose, for a total of only 3,145,090 people having received at least one vaccine dose. That’s 1,729,035 fewer people with at least some protection by May 1, the day when ICU cases peaked in Ontario.

Those vaccinated between April 3 and May 1 were mostly people over the age of 50 or those with significant comorbidities and therefore the greatest risk of serious illness or death. So, having 1.7 million fewer people having at least some protection at a time when Ontario had 20-30 infections per 100,000 people every day, would have been potentially catastrophic. An additional 400 infections a day, in a group in which the serious illness rate could be 10 per cent or more, would almost certainly have pushed our ICU numbers and hospitalizations beyond a sustainable level.

Of course, a single dose of a two-dose vaccination does not confer maximum protection, though the data suggests that protection from serious illness and death is quite robust even following a single dose. And while those 2.1 million who would have received a second dose earlier in the alternate scenario would have had even better protection from COVID-19 than we observed, this is of arguably lower consequence compared to the impending catastrophe in ICUs due to the limited number of infections seen in partially immunized people in Ontario.

While we’ve made assumptions with these figures and considered the impact of direct protection conferred by vaccination and not the impacts of reduced transmission, it’s clear that with our ICUs on the brink of being overwhelmed, the strategy to delay second doses almost certainly helped to avert catastrophe.

This is not meant to criticize those who expressed reasonable concern about prolonging the interval between vaccine doses. And with Canada’s vaccine supply increasing and becoming more reliable, provinces are beginning to administer second doses sooner than the up-to-16-week interval initially recommended by NACI. But in a pandemic marked by difficult decisions, uncertainty, regret and public backlash, it is important to acknowledge a decision that probably saved many lives.

The comments section is closed.

Thanks for providing some context. Our post mortems of this pandemic will focus on both what worked and what did not work. In the mean time, we can only hope that the press will give as much airtime to what did work as to what did not work.