“D’oh!”

That is what I said when I got the call. I was the palliative physician on call for the weekend and my nurse had just called me about a patient in the community. The weekend physician on call for palliative care in our area covers our two 10-bed residential hospices, the 20-bed palliative care unit and 250+ community-based patients. Yet this patient was not in the “system” – “Hank” Henry Fedak had somehow slipped through the cracks.

His son, Brian, called the Hospice of Windsor in a panic. Hank, 91, had just been discharged from hospital on a Friday afternoon (never a good idea). He had a longstanding history of congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation and had been hospitalized twice in the past 30 days.

He was discharged in “stable condition” and the plan was to await long-term care placement in the community. He had personal support worker help but no visiting nurse or other home and community care supports. He was not sent home with medications to support a comfort-care approach, known commonly as a symptom response kit or SRK.

Yet, here he was, two days later, dying. Since discharge, Hank’s condition had deteriorated. He was confused, delirious and bedbound. During a period of lucidity, Hank had expressed to Brian that he did not want to return to hospital. Brian had now reached out to the hospice in desperation, asking for help navigating the health-care system.

Clearly, this gentleman was in the terminal phase of his illness and would benefit from a palliative approach. But Hank’s situation also highlights the difficulty that clinicians have identifying patients who would benefit from this approach.

There are two ways to identify these patients. This first reminds me a lot of Homer Simpson, the lovable, well-intentioned cartoon husband and father of three on the long running Fox series The Simpsons. “Facts are meaningless. You could use facts to prove anything that’s even remotely true,” Homer maintains.

This is how we usually identify patients who would benefit from a palliative approach. We eyeball patients and feel that we can identify them using strictly clinical judgement.

By no means am I saying that Hank didn’t get proper or appropriate care while in hospital. Rather, the purpose is to underline the inadequacy of our current methods. Unfortunately, we know that physicians are not very good at prognosticating serious illness and often we err on the side of optimism. This is particularly difficult in non-cancer diagnoses such as kidney failure, lung disease, dementia or congestive heart failure like Hank had.

But even beyond the eyeball test, our methods of promoting early identification have also shown limited effectiveness. The Surprise Question (SQ) – “Would you be surprised if this patient died in the next year?” – has been incorporated into many such efforts. But the SQ has a record of poor sensitivity and a low positive predictive value, meaning that you miss roughly a third of the dying and that two-thirds of the people identified by it are not actually close to the end of life. And in the non-cancer population, these numbers are even worse.

But perhaps the biggest issue with the SQ is that, like the eyeball test, it requires front-line providers who remember (and are willing) to use it. Outside of a study, where research staff are prompting clinicians to remember to use the SQ, uptake can be poor.

But there are newer approaches that may offer a way forward. The other Homer, or HOMR, is the Hospital-patient One Year Mortality Risk assessment.

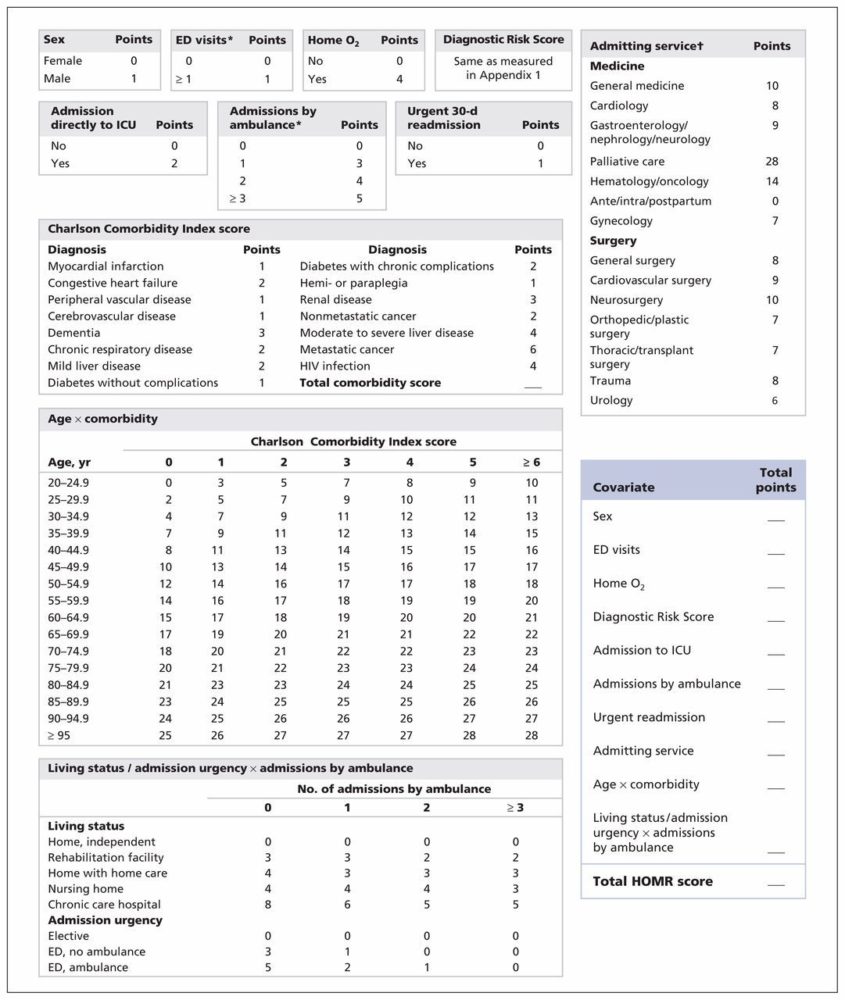

The model consists of covariates whose values are determined at admission using routinely collected health administrative data. These covariates include patient demographics (age, sex and living status); health burden (measured using the Charlson Comorbidity Index score, home oxygen status and the number of visits to emergency departments and admissions to hospital by ambulance in the previous year); and acuity of illness (admission urgency and hospital service, direct admission to an intensive care unit and whether the admission was an urgent readmission to hospital). It is the most accurate mortality prediction tool ever published.

HOMR can be calculated in “real time” by a program that automatically pulls data from the patient’s electronic medical record at the time of admission. This program can flag patients who have an elevated risk of mortality in the coming year and recommend (among other things) an individualized assessment of needs, a clarification of goals of care and a discharge plan. This approach is both more accurate and more reliable than any provider-dependent approach could hope to be.

If HOMR had been in use when Hank was admitted, he would have been flagged. A simple calculation shows that Hank would have scored 46 (see chart below) on the scale. Based on this score, HOMR forecasted that Hank had a 63.3 per cent chance of dying in the next year. This certainly would have raised a flag with the admitting team and would have alerted his admitting physician to consider a palliative approach to care or to consult the in-patient palliative care service for assistance.

While being flagged would not have changed the ultimate outcome, what HOMR would have done is ensure that Hank was discharged with the proper supports already in place, that a holistic plan for care would have already been discussed with Hank and his son, and that when Hank declined, Brian would have known who to contact and how to manage his father’s care at home.

In Hank’s case, thanks to a superb hospice nurse educator (Jessica Audet) and visiting nurse (Jenny), we were able to rapidly increase home-care supports for Hank. Services were initiated within hours. Medications were prescribed to manage Hank’s delirium and shortness of breath. A do-not resuscitate order and home pronouncement plan were put in place.

Hank died at home that night, comfortable and in the presence of his family.

Can I get a “woo-hoo?”

To use an aviation term, Hank’s case was a “near miss.” Under most circumstances, Hank likely would have ended up back in hospital where he would have died alone and isolated. But while we are proud of the program’s ability to prevent this tragedy, we recognize that most communities do not have the same palliative care resources we have in Windsor and that the best way to address these near misses is to make sure they never happen in the first place.

The Ontario Palliative Care Network has published a resource document that identifies tools such as HOMR that can assist health-care workers with identifying patients who would benefit from a palliative approach to care. The RESPECT tool, which also uses administrative data to predict mortality risk, can function in long-term care and the home care setting to achieve the same goals.

By using early identification tools, we can find these patients before they fall through the cracks and improve outcomes for patients.

This article reflects the views and conclusions of the author and does not necessarily reflect those of Ontario Health. No endorsement by Ontario Health is intended or should be inferred.

The comments section is closed.

Thanks Caitlin. My hope is that every hospital ends up using HOMR. Looking forward to hearing about all your successes.

As always, thanks for writing about this. This is something we will be working on shortly at NYGH, and this story helps to reinforce the importance of HOMR in providing a patient- and family-centred end-of-life experience.

Thanks Caitlin. My hope is that every hospital ends up using HOMR. Looking forward to hearing about all your successes.

Looking forward to your questions and comments.

Dr. Downar always appreciates dirty limericks.