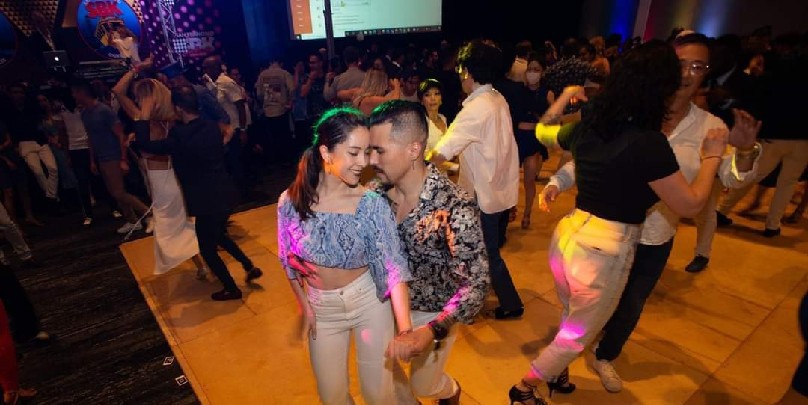

Six hundred mostly unmasked people from across the globe, dancing cheek to cheek in pairs in a dimly lit hotel ballroom, switching partners every 10 minutes for 38 hours – in the midst of a pandemic wave.

That would be enough to make most people more than a little nervous, yet that’s what took place over an icy December long weekend at Denver’s Elevation Zouk Festival, a three-day convention that brought together dancers of zouk, a Brazilian partner dance based on the lambada. Similar events have been increasing in the United States since mid-2021 despite some COVID-19 outbreaks at the events.

Knowing they are putting their bodies on the line to have human connections, many dancers at the events are trying to manage their COVID risk through symptom surveys, mandatory vaccination and testing – a trial by fire that could give us a glimpse of what mass gatherings might look like in a post-pandemic world.

The year “2020 was completely hopeless, like one big, dark hole,” says Fae Hermann, full-time dancer and co-organizer of Elevation. “Being alone for a year takes a pretty heavy toll for a human being. A lot of people got ‘touch starvation.’ Dance is therapy for a lot of them.”

For Denver festival attendee Lily Jerissa Herreria, that therapy is essential. The physical distancing of the early pandemic led her to depression and significant weight gain, she says. “I didn’t feel connected to people … There’s something about being with your friends that you can’t get from Zoom meetings or dancing on your own.”

And for Sarah Nicole Littlefield of Baton Rouge, La.: “Dance has always been an escape for me – that happy place.” Newly pregnant in early 2021 and unvaccinated because of a medical condition, she decided to resume partner dancing anyway, judging that the rewards would outweigh the risks.

Those risks are significant. Last June in Linden, Ariz., a three-hour country dance with only 70 participants led to 24 cases of COVID and two deaths, according to The Arizona Republic.

Although the specific literature on COVID-19 transmission in partner dance is limited, Canada’s National Collaborating Centre for Environment Health listed six international clusters and outbreaks linked to dance in 2020. One such outbreak in South Korea led to 112 infections from a single dance instructor. Another in Detroit’s ballroom community led to an estimated three dozen deaths.

Beyond the health risks, event organizers also have a lot to lose.

In early March 2020, Ottawa organizer Helen Hsu was ready to host her own event, which was to attract international dancers. A physician, Hsu had heard of the approaching COVID-19 threat in medical circles.

“I pulled the plug on it just five days before – everybody thought I was insane,” she recalls.

But her intuition proved to be correct, as the World Health Organization announced a worldwide pandemic just days later. What followed was a cascade of COVID-19 waves and, with them, event cancellations that carried major consequences for organizers of mass events.

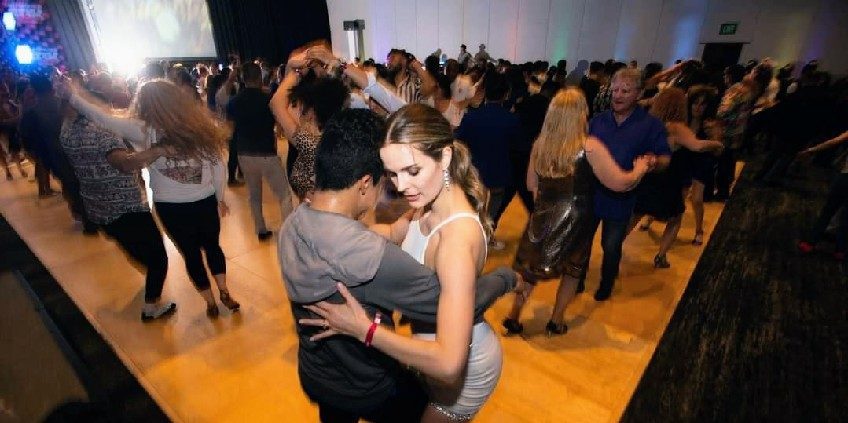

“If you’re an attendee, you might lose a thousand bucks. But man, if you’re an organizer, you could lose your house,” says Mao Mambo, co-organizer of the San Francisco SBK Congress, an annual convention that draws up to 3,000 dancers of salsa, bachata and kizomba, an African partner dance.

Although Mambo did not lose his house, Hermann and Denver co-organizer Bruno Miranda say they lost tens of thousands of dollars when they canceled Elevation in 2020.

“We can’t live like this forever,” says Hermann of the roller coaster of on-and-off restrictions decimating the industry. “We’ve got to return to some kind of normalcy at some point.”

However, it seems few can agree on what “normal” should be.

Miranda says some states seem to have their own culture around COVID-19 precautions. In Colorado, most people strongly believe in vaccination; in Florida, “you feel like the pandemic never happened. There are no masks, no requirements.”

Canada has its own variations on restrictions. Before Dec. 19, Ontario allowed dancing in bars and clubs with proof of vaccination, but currently prohibits it. Quebec, which until Dec. 20 allowed masked dancing, has since suspended all group activities indoors. Although Newfoundland does not mention dancing specifically, it mandates physical distancing for all formal gatherings. Alberta and the Northwest Territories explicitly state that indoor dancing is not permitted, while on Jan. 20, B.C. reopened dance classes, but not dance in other settings.

Toronto event organizer Darius Zi of COVID-19 says the mass gathering industry must adjust long-term to COVID, just as the airline industry adjusted to 9/11. “This is not going to go away. It’s here to stay,” he says.

But what does that change look like?

Zi’s solution is Danceplace Digital, an online platform he founded that assists with dance event management. Originally focusing on mobile app development, Zi switched Danceplace’s focus last year to COVID-19 mitigation strategies.

With help from Hsu and co-organizer Laura Riva, Zi adapted a symptom screening tool from Toronto’s Sinai Health to help dancers decide whether it’s safe to attend an event. It has since been translated into four languages. Zi also is piloting a dance-specific vaccination pass. It allows dancers to check-in with their vaccine details, similar to how one completes online check-in for a flight.

In addition to risk mitigation, Hsu says the way forward is about honesty: “We need to accept things as they are, not as we wish they could be … I don’t think it’s fair for the public to expect that we’ll go back to how things were in 2019.”

Resistance to inevitable change worsens suffering, says Hsu, who works in mental health and addictions. “Every time we underestimate COVID and the pandemic, we end up doing so at the peril of our own mental health. Suffering is pain plus resistance – but you have control over resistance.

“In the end, it’s better to just plan for the worst and hope for the best. That’s all you can do.”

Event photography by Os Hernandez. Cover image stock photography from Canva.

The comments section is closed.

Thank you so much for the article, Anthony! I’ve forwarded this to members of my Lindy hop community in Ottawa.