Myles Leslie, an associate professor at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy, had never received a piece of hate mail before July. But, since launching a clinical tool to help physicians navigate vaccine hesitancy with their patients, this kind of message has become a regular occurrence.

The guide was a response to patients “calling into question (physicians’) medical training and (their) ability to know things and whether (they were) a good person,” he says. “It was really, really hard.”

Leslie and his research team knew that physicians wanted information on what was working for other doctors when it came to difficult questions, so they conducted interviews and collated advice and suggestions. He says at least 17,000 individual online viewers have opened the guide in the four months it has been available.

“You don’t have to walk into that room never having thought about this before and go, ‘Whoa, what am I supposed to do with that?’ Here are some other people who have gone through this and this is how they are thinking about it.”

Not everyone who is hesitant about the COVID-19 vaccine reacts as strenuously as some of the people who comment on Leslie’s work. But the confrontational messages are not unique.

Myles Leslie, an associate professor at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy.

In an October statement, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta said it was “saddened to learn of an increase in violent threats against physicians and support staff, as well as personal attacks, threats – including death threats – and abusive language directed at physicians on social media.”

While a spokesperson would not elaborate, citing the college’s confidential complaints process, she did specify that “aggressive behaviour has stemmed from conversations around vaccinations.”

The threats are occurring across the country. On Nov. 8, Ottawa family physician Nili Kaplan-Myrth wrote in the Globe and Mail that as a doctor promoting vaccination, “I am afraid. I can no longer walk to work alone. I startle awake at night.”

She had learned of a threat on her life made by someone in a complaint to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario because she had been advocating for COVID-19 vaccinations. The college is under fire from physicians for its 12-day delay in informing Kaplan-Myrth about the risk.

And in a statement Nov. 25, the Canadian Medical Association asked Ottawa to “establish a new offence in the Criminal Code of Canada to include threats, violence, harassment and intimidation of health-care workers both in person and online.”

This social unrest during the pandemic has captured the attention of Gul Deniz Salali, an anthropologist at University College London. She can usually be found working with hunter-gatherer communities in Congo. As for many others, however, the pandemic cancelled Salali’s field plans. She decided to go home to Turkey for a while and there, she noticed something intriguing.

“There was so much speculation about the origin of the novel coronavirus,” Salali says. “I asked myself why, in some countries, do people seem more skeptical about the information they receive? And how can we tackle vaccine hesitancy using predictions from what we know about human behaviour?”

Salali teamed up with social psychologist Mete Sefa Uysal to launch an online survey in May 2020 asking people in Turkey and the United Kingdom about their willingness to receive a vaccine should one become available.

About 1,000 people in the U.K. and 4,000 in Turkey responded. Three per cent in both countries said they would refuse a COVID-19 vaccine. In the U.K., 14 per cent said they were hesitant while that rate was much higher in Turkey, where 31 per cent said they were undecided.

It turns out those numbers could be traced in part to beliefs about the origin of the virus – 63 per cent of British respondents said they believed in the natural origin of the virus, whereas only 54 per cent of Turks said the same. The findings were published in Psychological Medicine.

“There was a very strong link between being hesitant about the COVID-19 vaccine and believing in a man-made origin of the novel coronavirus,” Salali says. “It made us want to study how beliefs are linked to hesitancy in getting vaccines.”

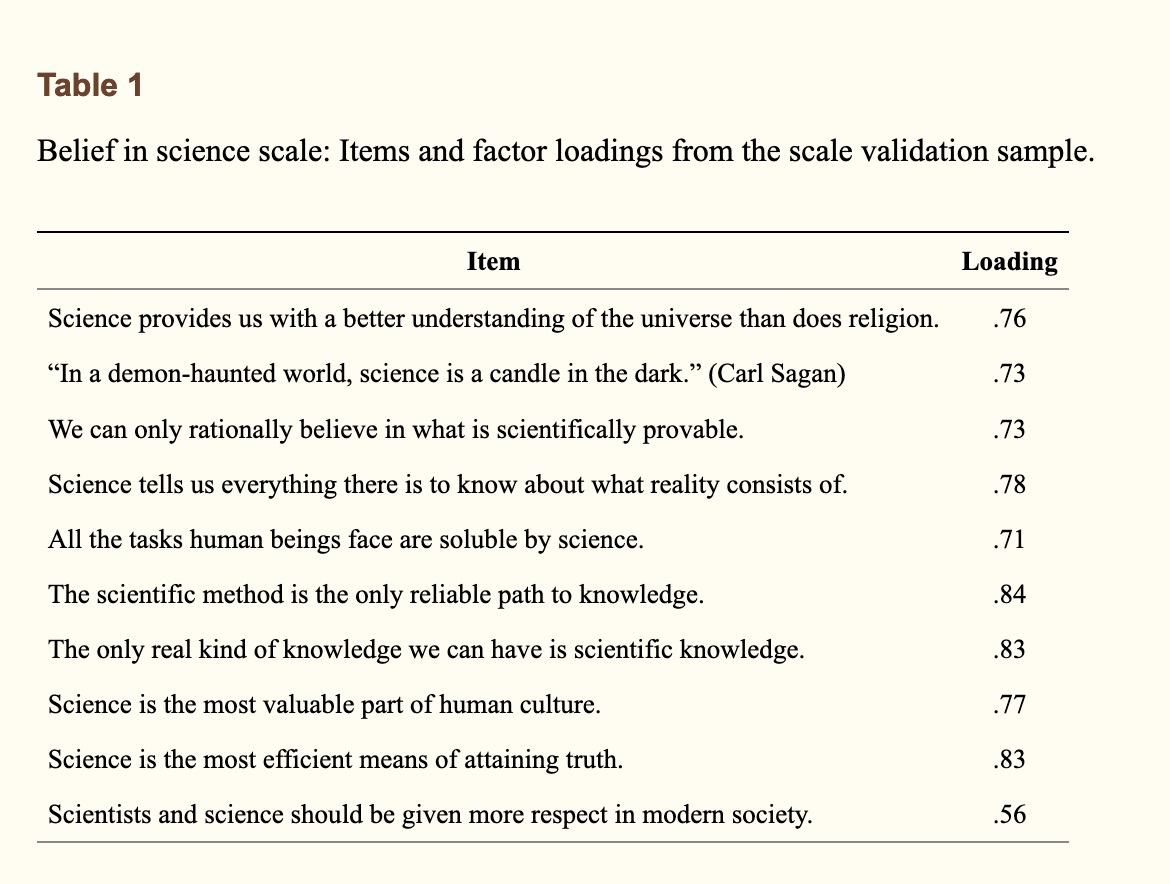

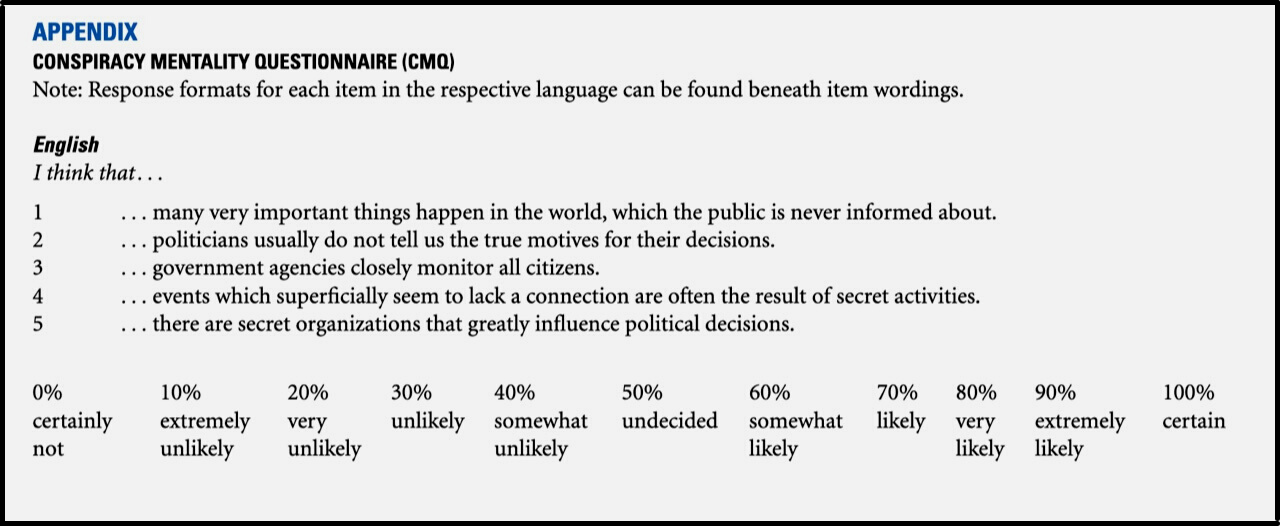

Knowing that previous research had linked acceptance of vaccines to conspiracy beliefs and to belief in science, Salali and Uysal created a new survey. This time, they included the Belief in Science Scale (Box 1), which asks to what degree people feel science is the best way to understand the universe and make decisions. They also added the Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire (Box 2), which asks people to what degree they feel monitored by the government and believe that many important decisions are made in secret.

They again invited people from the U.K. and Turkey to participate, and added people from the United States. By the time the new survey rolled out, COVID-19 vaccines were being widely administered. About 1,500 from each country responded, and their results were released in a July 2021 preprint.

As Salali and Uysal predicted, people who had high scores on the science belief scale were more likely to accept a vaccine. But cross-culturally, the results were not so tidy. Turkish respondents, on average, espoused significantly higher trust in science than did people in the U.S.; on the other hand, they also had the lowest level of trust in vaccines of the three countries.

Salali says this is where conspiracy mentality comes in. “Many more participants in Turkey agreed with (conspiracy) statements and believing in conspiracies is highly linked to vaccine hesitancy.”

Other cross-cultural comparisons were a bit messy, too. Increasing age made people more hesitant about the vaccine in Turkey, but less hesitant in the U.K. and the U.S. In the U.K., men and women were equally hesitant; in the U.S., women were slightly more likely to be vaccine-hesitant, whereas in Turkey it was men. In Turkey, political orientation toward the left was associated with vaccine hesitancy; in the U.S., hesitancy was associated with right-leaning beliefs. In none of the countries was level of education significantly correlated with vaccine hesitancy, but financial satisfaction was: being more secure financially increased likelihood of vaccine acceptance.

Overall, though, Salali and Uysal’s findings point to belief in conspiracies as the strongest cross-cultural predictor of vaccine hesitancy. “The interesting question now,” Salali says, “is why people believe in these conspiracies.”

While their work on this question is underway, Salali says it seems to have something to do with a person’s relationship with freedom. Some people have a strong negative response to believing their freedom of choice is in danger, or to believing they’re being made to conform to what the majority wants. In psychology, this is called reactivity. And you guessed it: there’s a scale for that, too. Salali says people who have high reactivity scores are more likely to believe in conspiracies because they offer “alternative explanations to the mainstream.”

Gul Deniz Salali, an anthropologist at University College London.

All of this resonates with Leslie in Calgary. “For (some) of the people who are hesitant or resistant,” he says, COVID-19 “is kind of a microbiological version of Donald Trump. It’s the thing that touches them in the middle about what is wrong with the universe at the moment. (It’s like they’re saying) ‘I feel like I can’t control anything anymore. I make good choices, I’ve taken on all of these responsibilities that have been given to me, and I’m no further ahead. Well, damn it, I’m planting my flag this time. I’m not doing this anymore.’

“I think a lot of this is a scream. It’s fear.”

Leslie says the last thing a physician should do when faced with this kind of fear, which is outside the normal realm of medicine, is to settle into “that science-deficit communication model (and say), ‘Well, you know what the data say.’” Instead, he suggests this: “Give (the patient) the space to make the point, and (don’t) gainsay it. Take it in, and then push back out with, ‘Wow, OK. But it’s my job to be on your side, taking care of your health, and I’m hoping that we can talk about this again.’”

But if vaccine hesitancy, at least for some, is linked to existential doom, to psychological reactivity, and to a desire for alternative explanations, are these characteristics modifiable? Are conspiracy-mindedness and psychological reactivity fixed traits? Or can people begin to react less strongly to attempts at persuasion?

Salali says pointing out the benefits of vaccination to a vaccine-hesitant person can backfire. “But I don’t like calling anything fixed. We know that people change their behaviour based on environmental influence, on costs and benefits. With vaccine passports, the cost of not getting the vaccine is high. So, people may say, ‘OK, I’m going to change my decision on this.’”

And while the desire for alternative explanations and skepticism can be powerful vaccine deterrents for some, Salali says they can be modulated by a person’s orientation toward the common good. “Regardless of their psychological reactivity score, a participant (who is) high on collectivism (is likely) to accept the COVID-19 vaccine.”

But while people might be persuaded to take the vaccine themselves for the common good, Leslie is preparing to enter the next stage of pandemic response: difficult conversations involving vaccinating children. His team is at work now working on a version of the hesitancy tool for kids and parents. He hopes to release the updated guide by the end of the year.

“We are significantly more risk-averse on behalf of our children than we are for ourselves. Period. The world has been set up, the Anglo-American world particularly, to make everybody feel super responsible for themselves. ‘If you’re doing a shitty job taking care of your kids, then that’s on you.’ That’s the dark black bit in the middle. OK. Scream it. Now tell me: What would make you feel like a better mother? I can work with that.”

The comments section is closed.

What if “conspiracy theories” are often facts we are simply unable to accept? Why does vaccine hesitancy = being a conspiracy theorist? Pharmaceutical corporations are rich. They fund political campaigns. They conduct their own biased research which governments seem to have no trouble embracing. They influence what is learned in medical schools throughout the world. They discredit viable natural alternatives. With Covid 19, they have had a massive influence on government policies. Governments feel obligated to make it look like they are “doing something” to help people, so they push for vaccines despite this still being a huge clinical trial, and vilify the unvaccinated. If this was done from a place of concern and altruism, these companies would donate these vaccines they believe so strongly in, to countries like Africa with a 5% vaccination rate. And what about the data? It’s all over the place! Last week we are told that those contracting the virus are largely the unvaccinated (which doesn’t make sense given the 85% vaccination rates, and others who are recovered and immune). This week they tell us that 72% of new cases are in the double vaccinated! What are we supposed to believe? I am a hard believer in good science, but all of this stinks of organizations seeking financial gain. Conspiracy? I think NOT.

Great response Adelaide – couldn’t have said it better. Too bad journalists haven’t been properly trained in unbiased reporting. Your response is clearly unbiased and raises questions instead of creating the black and white thinking which causes most conflicts in debate. Thanks for responding with a little bit of ‘grey’.