As Canada grapples with the dual crises of COVID-19 and police brutality and their disproportionate impact on Black, Indigenous and people of colour, we have seen academic institutions and healthcare organizations commit to advancing racial justice and adopting anti-racist practices. As researchers, advocates and public health professionals, we know that anti-Black racism is a pervasive and insidious health issue. But how can we translate solidarity statements into tangible action?

One necessary step is making space for more diverse voices in the health sector.

It’s no surprise then that this sector has struggled to meet the needs of Black, Indigenous and other communities of colour. For decades, non-white Canadian health professionals have called for a more diverse workforce and for more substantive anti-racist health policies and practices.

This is a long-standing problem that cannot be addressed overnight. However, there are real solutions that health institutions can adopt right now to help transform the sector from the inside out.

Let’s start at the top: healthcare leadership. To truly advance racial justice at an organizational level, it is critical to have leadership that reflects the populations served by the organization. Unfortunately, we cannot see the full picture of diversity in healthcare leadership because, for the most part, organizations don’t collect and report this information. The limited data we do have paints a disappointing picture.

Despite Canada’s ethnically, linguistically and racially diverse population, the Canadian health sector is still largely white in management and governance. For example, a 2013 survey found that in the Greater Toronto Area, only 16 per cent of senior management and 14 per cent of board members in the healthcare sector identify as racialized even though many municipalities in the GTA have close to 50 per cent or more of their population identifying as such.

Ultimately, organizations can’t fix what they don’t measure. The sector needs more transparency around diversity in leadership. Senator Ratna Omidvar recently penned an open letter calling on the charitable sector to lead the way and voluntarily review and disclose demographic data of its board members. Organizations with a health mandate such as hospitals, community health centres and public health units can and should follow this approach. Such metrics would give ample data for analysis and promote transparency and, most importantly, drive more equitable representation in leadership.

But it’s not just leadership: it’s also important to diversify the workforce that cares for patients. Failing to do so jeopardizes patient care. One of the biggest barriers to creating an anti-racist health system is the lack of diversity in health professions

This has been an issue for decades but we are finally seeing some slow progress from some Canadian medical schools. The University of Toronto has implemented the Black Student Application Program that aims to increase Black representation in medicine. This year, the Faculty of Medicine will be welcoming 24 Black students into its incoming class, a sharp contrast to just a few years ago when there was only one incoming Black student. Likewise, in its commitment to reduce systemic barriers, Queen’s University has allocated all 10 of its Queen’s University Accelerated Route to Medical School seats to Black and Indigenous high school students.

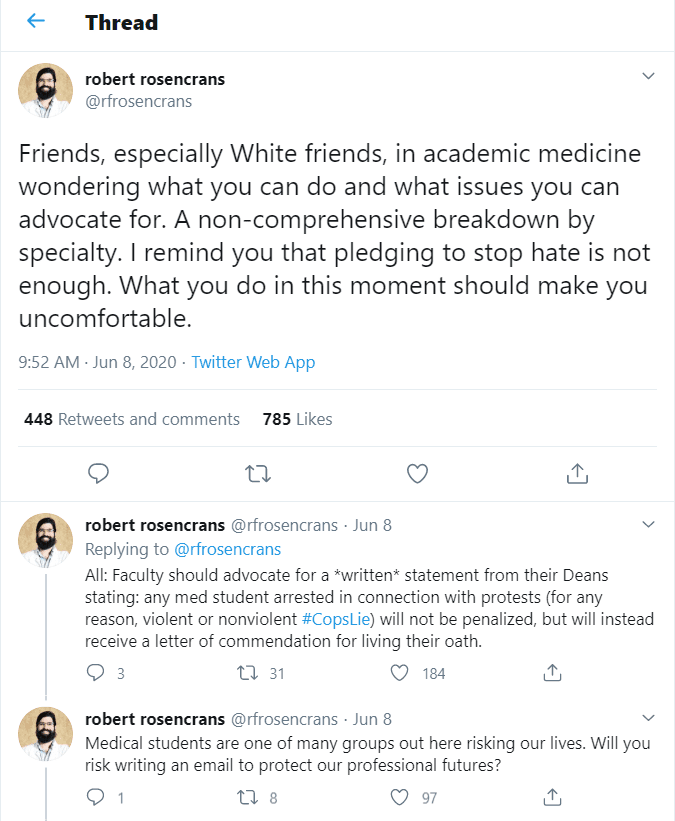

Creating a more diverse health workforce is more than a social justice goal: it meaningfully improves patient care. As highlighted in a recent twitter thread, all too often students learn to make decisions about patient care based on outdated, poorly understood or just plain inaccurate information about health and disease in people of different races. When the medical baseline is centred on the “70kg white male,” we fail to address racial differences in disease onset, presentation and treatment. Bringing diverse voices to medicine means that we can finally challenge these inaccuracies. Recently, Malone Mukwende, a second year University of London medical student, developed a teaching handbook for students and physicians called Mind the Gap: A Handbook of Clinical Signs in Black and Brown Skin.

Finally, it is also critical that these efforts aren’t limited to a single initiative or single department. All too often, institutions create Diversity, Equity and Inclusion initiatives that are seen as separate from the work of teaching trainees and treating patients. Professionals of colour are often asked to lead a committee or step into a newly formed leadership role whose focus is strictly administrative. Add in that their work often goes unseen and unrewarded – a phenomenon known as the minority tax. It’s important to keep in mind that professionals of colour bring a unique skill set and lens that enriches our health system across the board. Diversity should be apparent across all departments and all levels: from hospital CEOs and academic faculty to care providers and students.

When addressing anti-Black racism, we need to be specific in our diagnosis of symptoms and in what we prescribe as policy solutions. We have highlighted three concrete steps organizations can take but we can’t stop there. Part of the anti-racist approach also requires policy advocacy to promote a more equitable distribution of the social determinants of health such as adequate housing, decent work opportunities and income security for all. Then, and only then, can we ensure our commitments to advance racial justice and address anti-Black racism can translate into effective action benefiting everyone.

All authors are graduates of the Masters of Public Health program at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto and were fellows at the Wellesley Institute.

The comments section is closed.