Aging family doctors in Ontario’s smaller towns present a significant challenge to health-care access.

A recent analysis conducted by CareCanada reveals alarming disparities in the age distribution of family doctors, underscoring the challenges faced by residents in these communities.

The research is based on a comprehensive analysis using available data for 16,416 family doctors, with a primary focus on the age distribution of family doctors in Ontario towns/cities. Data was obtained from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO), which provided valuable insights into the demographic makeup of family doctors across different regions.

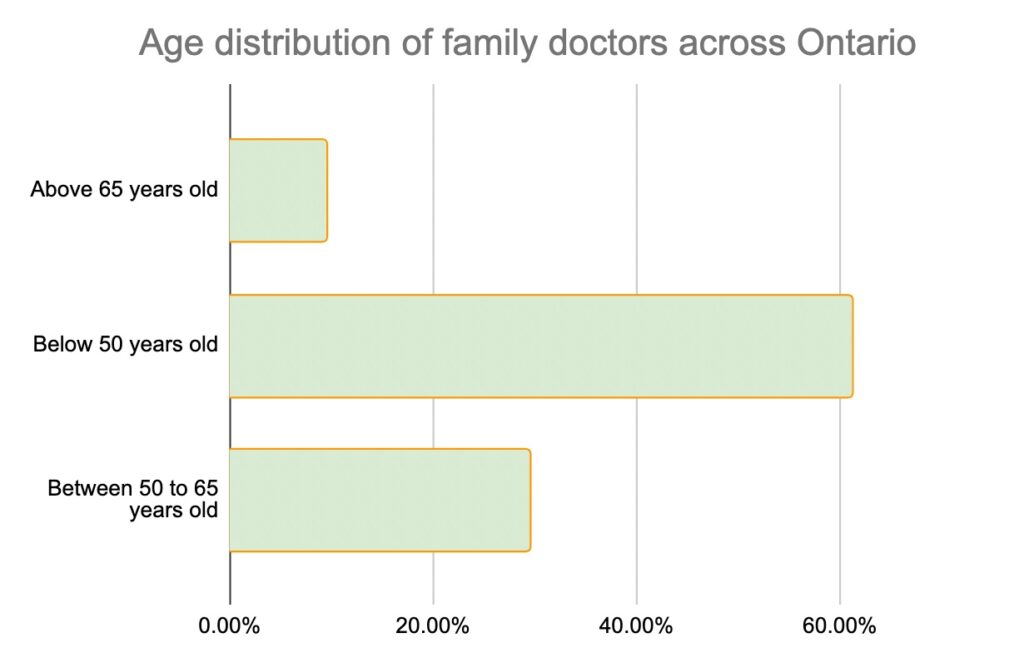

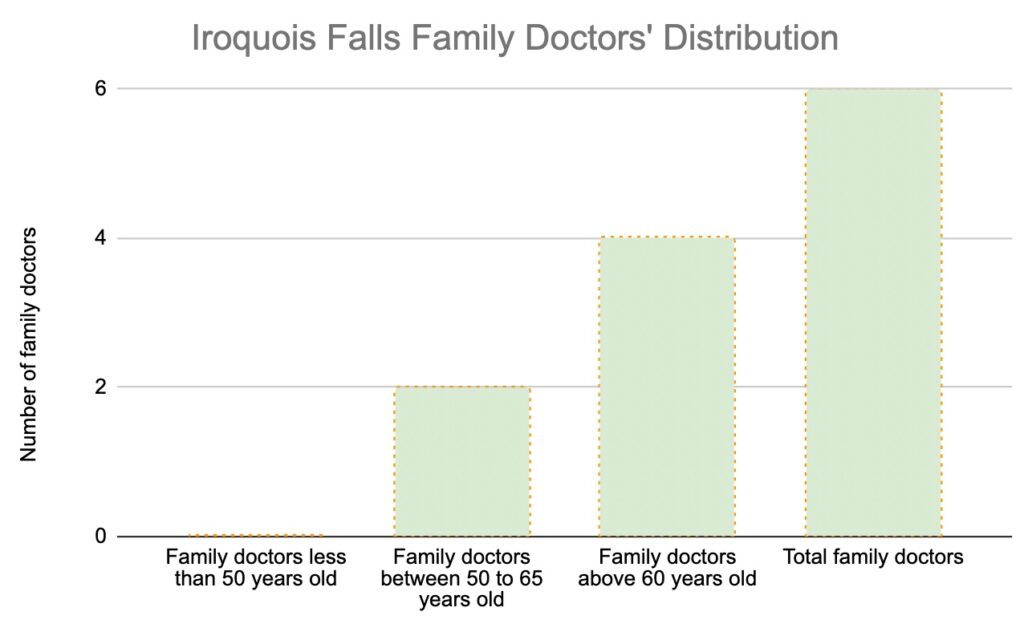

Though the study reveals a reasonably balanced distribution of family doctors across Ontario based on age, closer examination uncovers concerning statistics. Iroquois Falls, a town in Northern Ontario, stands out with an overwhelming majority of family doctors falling into the above-65 age category, comprising 66.67 per cent of the total. This disproportionate distribution raises concerns about future shortages as these practitioners approach retirement age. With limited replacements in the younger age brackets and 58 kilometres to the closest city, Iroquois Falls might face significant challenges in maintaining accessible health-care services for its growing population.

Furthermore, the data highlights several towns exclusively relying on a single family doctor who is older than 65, indicating a potential scarcity of younger practitioners and a looming health-care gap. These towns include Brechin, Clifford, Cumberland, Dutton, Dwight, Elizabethtown, Islington, Katrine, Killarney, Moose Creek, Pickle Lake, Port Loring, Portland, Puslinch, Tiny, Tiverton, Whitney, Woodview and Ripley.

The disproportionate distribution of family doctors in certain towns, where all practitioners are above the age of 65, poses significant consequences for health-care provision. As these doctors near retirement, there is a risk of insufficient replacements in the younger age brackets. Residents in these towns may face challenges in accessing necessary health-care services, especially considering the long distances often separating them from larger cities.

The potential consequences of this imbalance are dire: longer wait times for appointments, reduced access to specialized care and overall compromised quality of health care. The lack of younger doctors also impacts the continuity of care for patients, as they may face the challenge of transitioning to new health-care providers or travelling long distances to seek medical attention.

Addressing the disparities in the age distribution of family doctors and promoting equitable health care requires a multi-faceted approach. CareCanada proposes the following strategies:

Targeted incentives: Implementing incentives, such as student loan forgiveness programs, grants or bonuses, can attract and retain doctors in regions facing shortages. These initiatives would encourage newly graduated doctors to practice in underserved towns and rural areas. By alleviating the financial burden associated with medical education, young doctors are more likely to choose locations where their services are most needed.

Flexibility in practice locations: Facilitating the ability of family doctors to practice in multiple locations enhances flexibility and encourages service provision in both urban centres and underserved areas. Streamlining administrative processes can remove barriers and incentivize doctors to offer their expertise in regions with limited health-care resources. Telemedicine and virtual-care options can also bridge the geographical divide, ensuring that patients in rural areas have access to medical consultations and follow-up care without the need for extensive travel.

Collaboration and community engagement: Enhanced collaboration between health-care organizations, policymakers and local communities is crucial. A comprehensive strategy, tailored to the unique challenges faced by each town, should consider specific demographics, geography and health-care infrastructure. Engaging local communities ensures their voices are heard and their health-care needs are addressed effectively. Town hall meetings, community forums and involvement of patient advocacy groups can facilitate open discussions, enabling stakeholders to work together toward sustainable solutions.

Investing in medical education and training: Increasing the number of medical schools and training programs in underserved regions can attract a diverse pool of young doctors. By establishing educational opportunities within these areas, aspiring physicians are more likely to develop connections and a sense of community, leading to higher chances of practicing in underserved towns. Additionally, offering specialized training programs in rural medicine can equip doctors with the necessary skills and knowledge to address the unique health-care challenges faced by these communities.

Telehealth and technology integration: Embracing advancements in telehealth and technology can play a pivotal role in bridging the health-care gap. Telehealth services, including remote consultations, remote monitoring and digital health records, can enhance access to care, particularly for individuals in remote areas. Investing in broadband infrastructure and ensuring internet access in underserved regions will enable the seamless delivery of telehealth services, making health-care more accessible and efficient.

Recruitment and retention strategies: Developing robust recruitment and retention strategies specific to rural areas is essential. Offering competitive compensation packages, professional development opportunities and support networks can make these regions more appealing for doctors seeking a fulfilling career. Collaborations with medical associations, residency programs and government agencies can facilitate targeted recruitment efforts to address the specific needs of underserved towns.

This research serves as a wake-up call, highlighting the urgent need to bridge the health-care gap in Ontario’s rural towns. Collaboration among stakeholders, along with investments in medical education, community engagement and technological advancements, will pave the way for a balanced and accessible health-care system.

By prioritizing health-care equity, we can build healthier communities and create a sustainable future for Ontario’s health-care landscape. It is imperative that policymakers, health-care organizations and local communities come together to implement these strategies and drive positive change. Only through concerted efforts can we ensure that every individual, regardless of geographic location, has equal access to the health care they

The comments section is closed.

0i6xva

Thanks for the article, it is indeed something that needed to be fix a long time ago. We all knew it was coming but we kept repeating over the years the same old system instead of being innovative. The rural and remote regions in Ontario had told everyone that it was coming and they did try hard to get heard. Who in Toronto did listen? I agree with the strategies to promote equitable healthcare but as a leader of a not for profit team base primary care organization I’m disappointed to see that providing team base primary care (the foundation of the health system) as a tool to attract primary care providers in remote and rural region is not part of the strategies. New grads family doctors want to work in team and they can’t because of a continuous lack of vision (and adequate funding) from some key stakeholders. The rural and remote communities in Ontario deserved a strategy that included team base primary care for everyone and now not at the next election and the other one after and the one after and the one after. Enough promises, it is time to act before it is too late.