There is no doubt primary care plays a vital role in reducing health inequities. Health systems with strong primary care have been shown in multiple studies to lower both the absolute numbers and the gap between people with low and high incomes when it comes to neonatal mortality, babies with low birth weight and deaths from cancer, stroke, heart and lung disease, while increasing life expectancy at the population level.

Even though health care in Canada is publicly funded, individuals with low incomes too often face barriers when it comes to accessing health-care services, which can adversely impact their overall health. For instance, the life expectancy in Montreal’s poorest neighbourhoods is 10 years shorter than in the richest ones, due to an interplay of unfavourable health determinants, including access barriers to primary-care services that are influenced by cultural, economic and educational factors. For example, recent data from Ontario found that people living in the poorest neighborhoods were the least likely to have a regular family doctor. The COVID-19 pandemic illustrated how low income – and other social determinants of health – coalesced with poor access to services; together these were associated with communities having higher numbers of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths.

At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly accelerated the adoption of virtual care in Canada, leading to major investments by the federal government and the emergence of multiple privately operated virtual-only services, some of which are not part of the publicly funded system.

But income plays a significant role in virtual care adoption and interest.

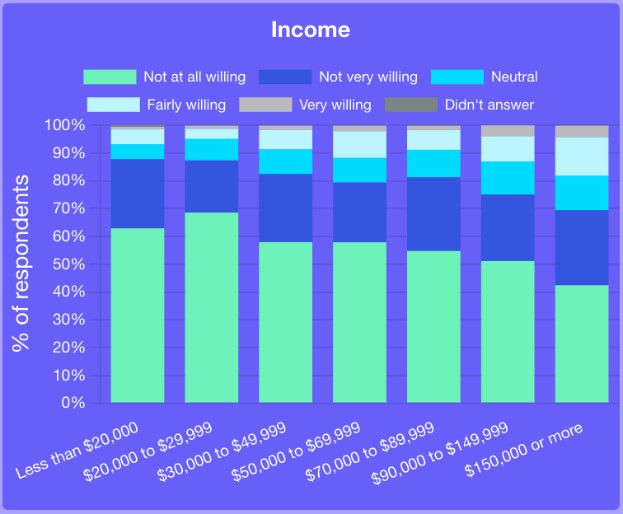

According to the OurCare survey, 69 per cent of individuals with an income of $150,000 or more say that they are not at all or not very willing to use virtual services that charge fees for services they could obtain for free through regular doctor or nurse practitioner visits. In comparison, 88 per cent of those with an income less than $20,000 say the same. If improperly regulated, the development of new private-pay virtual care services could potentially exacerbate existing disparities in access to care.

OurCare survey Question 37: How willing would you be to use new virtual services if the service charged you for things you could get for free if you saw your regular doctor or nurse practitioner? (Select the question from the dropdown menu)

But the barriers are not just financial. Almost half of adult Canadians have literacy skills below the high school level, significantly impacting their ability to access and understand health information, leading to further barriers in health-care access and utilization. The increasing reliance on digital technologies in health care could also have a significant impact on health-care access for vulnerable populations who experience lower digital literacy or who simply have less access to smartphones and computers.

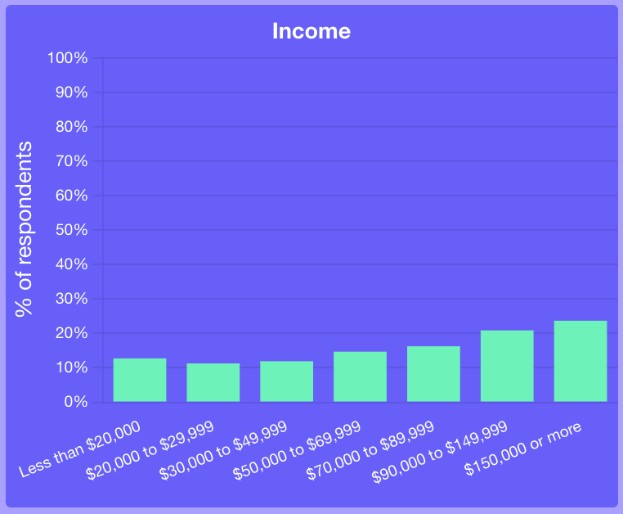

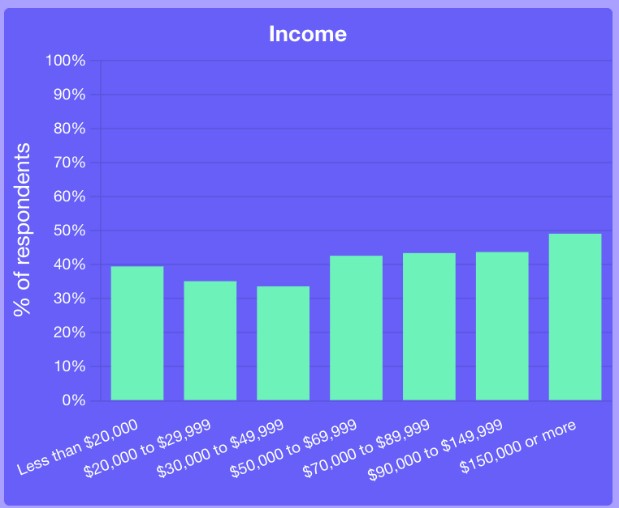

Low-income individuals are less inclined to use technology for medical communication and information access. In the past 12 months, only 13 per cent of those making less than $20,000 reported communicating with their family doctor via email and 39 per cent considered it important. In contrast, among those earning $150,000 or more, 24 per cent reported email communication with their family doctor and 49 per cent considered it important. These findings are consistent with results from a patient experience survey of more than 7,000 people in the Greater Toronto Area in the first few months of the pandemic that found people who reported difficulty making ends meet were less likely to feel comfortable with virtual options and less likely to want virtual options to continue post-pandemic.

OurCare survey Question 39: During the last 12 months, in what ways have you communicated with your family doctor or nurse practitioner?

OurCare survey Question 39: During the last 12 months, in what ways have you communicated with your family doctor or nurse practitioner?

OurCare survey Question 40 : Think about how you would like to get care from a family doctor or nurse practitioner. Which of the following are most important to you? (Select the question from the dropdown menu)

OurCare survey Question 40 : Think about how you would like to get care from a family doctor or nurse practitioner. Which of the following are most important to you? (Select the question from the dropdown menu)

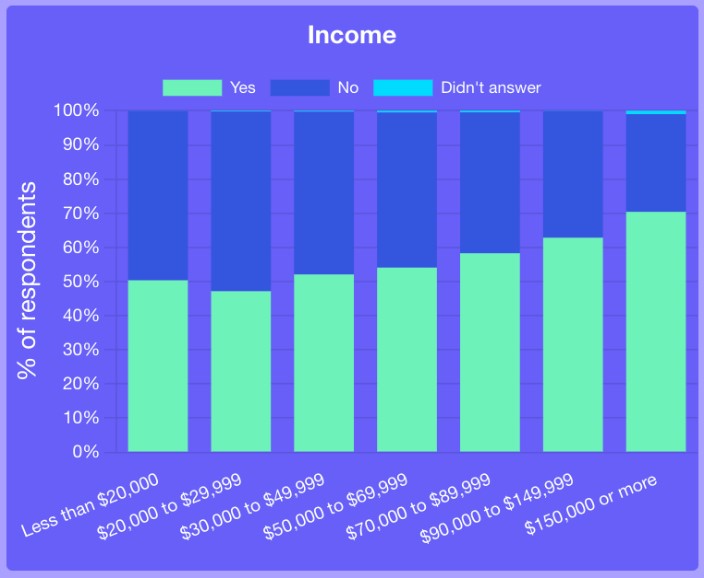

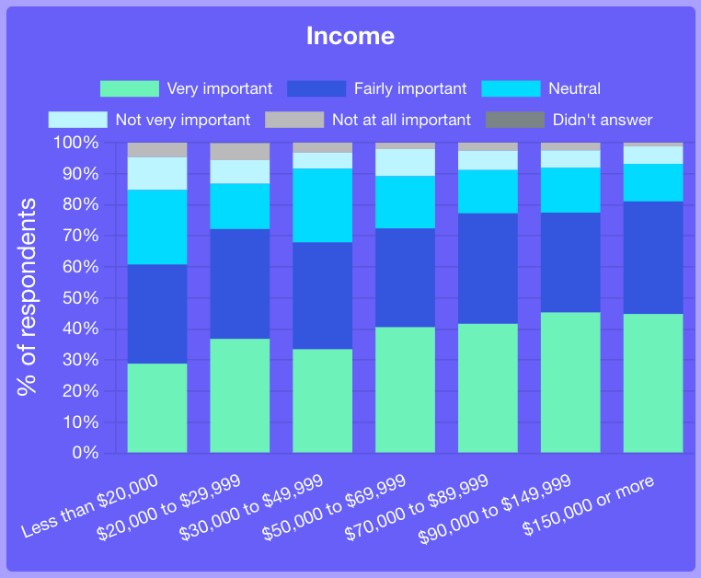

Moreover, accessing medical information via apps or websites is less common among low-income earners. While 50 per cent of respondents earning less than $20,000 per year reported using them, 70 per cent of those earning $150,000 or more did. Additionally, high earners place more importance on accessing personal health information online, with 81 per cent saying it’s very or fairly important, compared to 61 per cent of low earners.

OurCare survey Question 47: Have you ever used an app or website to see your medical information?

OurCare survey Question 47: Have you ever used an app or website to see your medical information?

OurCare survey Question 49: How important is it to you that you are able to look at your personal health information online? (Select the question from the dropdown menu)

OurCare survey Question 49: How important is it to you that you are able to look at your personal health information online? (Select the question from the dropdown menu)

There are multiple potential reasons for these findings, including people with a low income feeling less comfortable with using technology, lacking a good internet connection or data plan, or not having access to a personal phone or computer. More research is needed to understand what supports might level the playing field.

While technology can provide opportunities to improve access to care for underserved individuals who live in remote or rural areas, findings from the OurCare survey suggest the development of virtual models or information technologies can also widen existing disparities in health-care access.

OurCare is hosting Priorities Panels in five provinces, each one with 35 members of the public who roughly match the demographics of the region. The Ontario panel’s report, first to be published, emphasized equity as a core value of health systems and included a number of recommendations specific to virtual care, such as:

- expanding comprehensive virtual care to those with mobility challenges and in remote areas;

- creating publicly owned, 24/7 virtual care;

- offering access to a nurse or community paramedic who can virtually connect patients to a physician on a primary-care team free of charge;

- investing in affordable and reliable internet service and public spaces for virtual appointments to bridge the virtual divide.

In the coming months, OurCare will host panels in Quebec, Nova Scotia, British Columbia and Manitoba as well as 10 Community Roundtables across the country. Partnering with community organizations, these roundtables will focus on understanding and amplifying the priorities of marginalized and underserved communities.

Virtual care is a tool that can both widen and reduce care disparities. As we adopt new technologies, we must collectively ensure that we do not unintentionally worsen health inequalities. Through engagement with the public and marginalized communities, we can ensure virtual services are integrated into primary care in a way that improves health equity and closes gaps in access.

The comments section is closed.