Listen to patients.

That is the common mantra for those wanting to improve health care in Canada. Yet, all too often the people who use health-care services are missing from the conversation about how care can be organized differently.

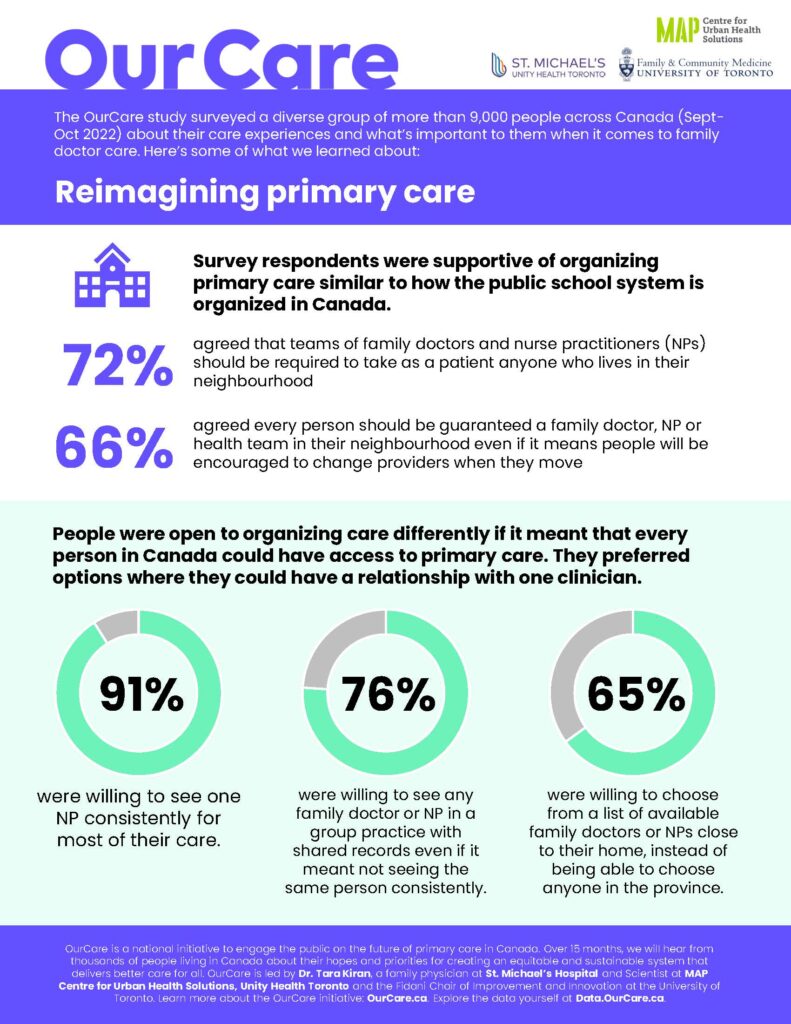

The results from the OurCare survey of more than 9,000 people across Canada last 2022 make clear that the public is open to change and new ways of organizing care.

Policy decisions are about choices and often those choices require trade-offs. The survey findings suggest that people understand this and are willing to accept trade-offs in the way they obtain their own care to ensure that everybody in Canada has access to a family doctor, nurse practitioner (NP) or primary-care team they can see regularly. And what’s more, the public’s priorities and preferences align with what we know from international evidence on primary-care reforms.

Across the board, there was strong agreement for proposals that maintained continuity of care with a single clinician – and if that’s not possible, then continuity of information between different clinicians in the same practice. These public priorities are in keeping with evidence from numerous studies that have found patients with high continuity relationships – those who see the same provider again and again – are more likely to receive recommended care, have better health, use the health system less and live longer.

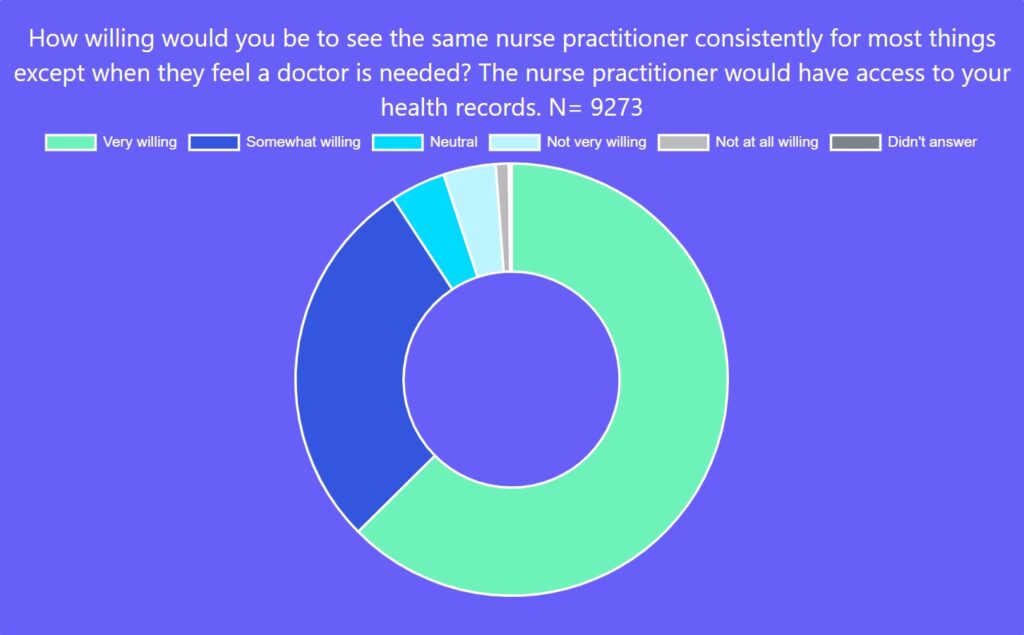

An overwhelming percentage of survey respondents (91 per cent) said they would be somewhat or very willing to see the same NP for most of their care except for when they felt a doctor was needed. This finding aligns with maintaining relationship continuity and is also an important endorsement for NPs who are not yet widely used in many parts of Canada to provide primary care.

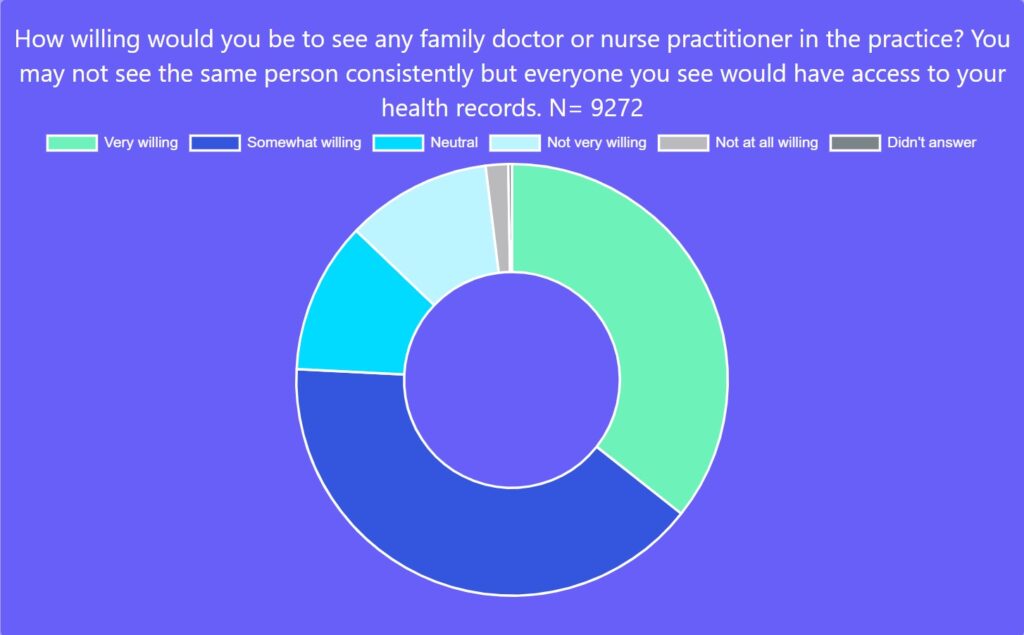

Seventy-six per cent were somewhat or very willing to see any family doctor or NP in a group practice with shared records even if it meant not seeing the same person consistently. Support for seeing another family doctor or NP in any practice in their region was supported but in a more muted fashion, with 64 per cent saying they would be willing to do so if the family doctor or NP could look up their records with permission. These findings imply most people would like a relationship with a clinician or a team, but many would settle for seeing any clinician who had access to their records.

Another major survey finding was that the majority of respondents were supportive of reorganizing primary care to make its accessibility similar to the public school system. When you move to a new neighbourhood, your children are guaranteed enrolment into the local public school. Generally, funding flows to schools to help them meet the needs of their community. It’s not perfect and sometimes, for example, infrastructure is slow in keeping pace with population growth. But ultimately communities ensure access to education for all children.

In some countries, primary care is organized similar to our public school system. For example, in Finland, patients are automatically registered to a local health centre; in the United Kingdom, people can choose from a handful of local practices near their home and those practices have to accept them. Not surprisingly, most people in these countries have access to a family doctor or place of care.

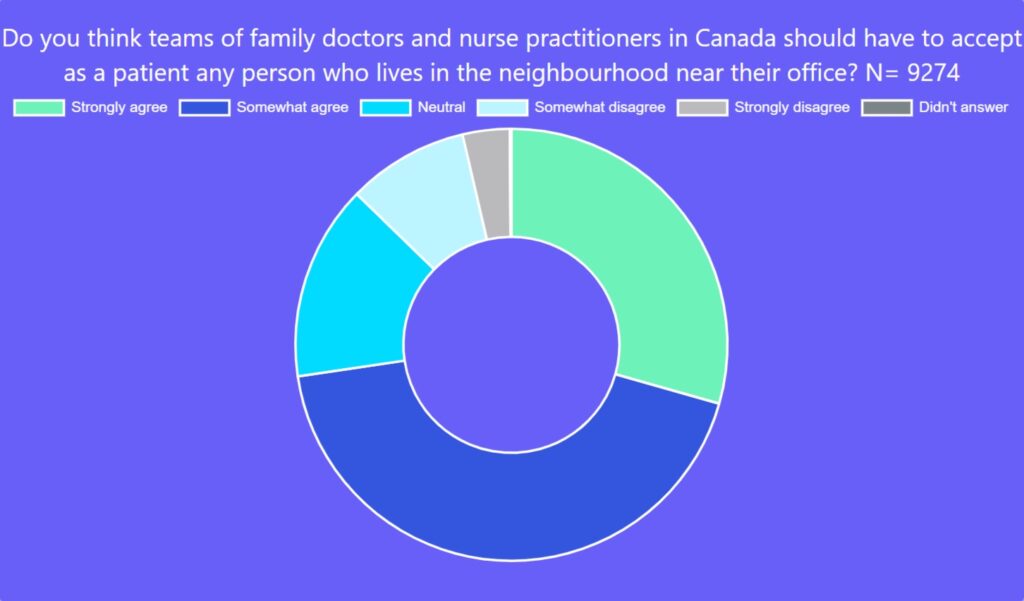

Seventy-two per cent of respondents to the OurCare survey strongly or somewhat agreed that family doctors and NPs in Canada should have to accept as a patient any person who lives in the neighbourhood near their office. Not surprisingly, more respondents who didn’t have a family doctor or NP (82 per cent) agreed with this proposal than respondents who did have a family doctor or NP (70 per cent).

Organizing care geographically is convenient and has the potential to guarantee access. But there is likely a trade-off in choice and being able to keep the same clinician when you move. Most, however, were willing to accept this trade-off. Sixty-six per cent somewhat or strongly agreed every person living in Canada should be guaranteed a family doctor, NP or health team in their neighbourhood, even if it meant patients would be encouraged to change providers when they moved to a different neighbourhood. And 65 per cent said they were very or somewhat willing to choose from a list of family doctors or NPs close to their home instead of being able to choose anyone in the province.

These survey findings align with recommendations from the OurCare Ontario Priorities Panel – a process that brought 35 ordinary Ontarians roughly representing the province’s demographics to learn and deliberate about primary care for almost 40 hours. A key recommendation from the panel was to move toward automatic rostering in which every person is automatically assigned to a primary-care practice. They recommended health teams be mandated to accept any patient from their catchment area. But they also articulated ways in which some patient choice should be maintained, for example, by allowing residents to choose between a few different health teams in their area.

Over the coming months, the OurCare team will be convening Priorities Panels in four other provinces in Canada, engaging members of the public in a dialogue about the future of primary care and understanding how priorities are similar or different across the country. We look forward to expanding and deepening the pool of ideas for reform together with these panels.

Results from the OurCare survey and the Ontario Priorities Panel have already demonstrated that the public is ready for bold change. The majority agree the system needs to be restructured and want to see reforms that support continuous relationships between a patient and a clinician or a team. Let’s not be afraid to act on their recommendations.

Explore the data yourself at data.ourcare.ca. For more information about OurCare, visit OurCare.ca.

The comments section is closed.

Thank you for the great research, clinic work and for publishing Healthy Debate – on top of everything else you do. ❤️

This series on the future of primary care as envisioned by members of the public is an important contribution to the public discourse. While many of the changes proposed are likely to be challenging to implement this one seems particularly challenging. I remind readers that public schools do not provide one on one relationships with students. Students are placed in classes and teachers assigned to a group of students. I think analogy with the provider-patient relationship is problematic.

There are many reasons that the proposed model is challenging but one of the most pressing is the immediate upheaval this policy bring to the current primary care system and established relationships. In research we did in Manitoba in 2017, there was significant variation in how close to home people accessed primary. In some areas less than 40% of residents received their care in their own neighborhood or MyHealth Team geographical area. The area with the highest congruence was only about 60%. The model in this article would require that half of the population would need to change where they access primary care!