There aren’t enough family doctors to go around.

Cuts to medical school enrolment in the 1990s have meant that a sizable proportion of family doctors today are over age 65 and nearing retirement. The pandemic seems to have spurred many family doctors to stop working; one in five Toronto-area doctors are thinking of closing their practice in the next five years. At the same time, fewer medical students are choosing family medicine and among those who do, fewer are choosing to practice longitudinal office-based care. Our population is growing, people are living longer, and family doctors seem to be caring for smaller panels of patients.

So, how can we ensure that everyone in Canada has access to high-quality primary care when there is a growing shortage of family doctors?

Part of the answer lies in team-based primary care – family doctors and nurse practitioners (NP) working together with nurses, social workers, pharmacists, dietitians, physiotherapists and/or other health professionals to care for patients collaboratively, sharing one health record and ideally working under one roof.

Done right, team-based care can expand the capacity of family doctors to care for more patients.

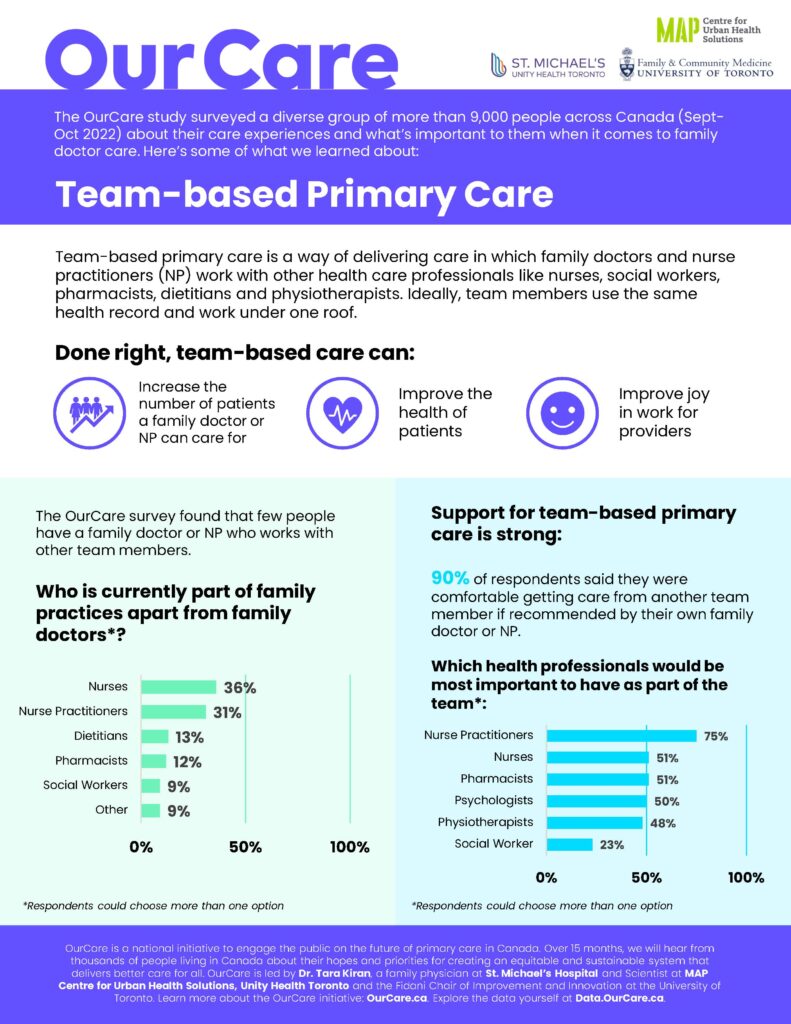

Results from the OurCare national research survey of more than 9,000 people in Canada demonstrate strong support for team-based primary care – but the results also highlight how few people have access to it right now.

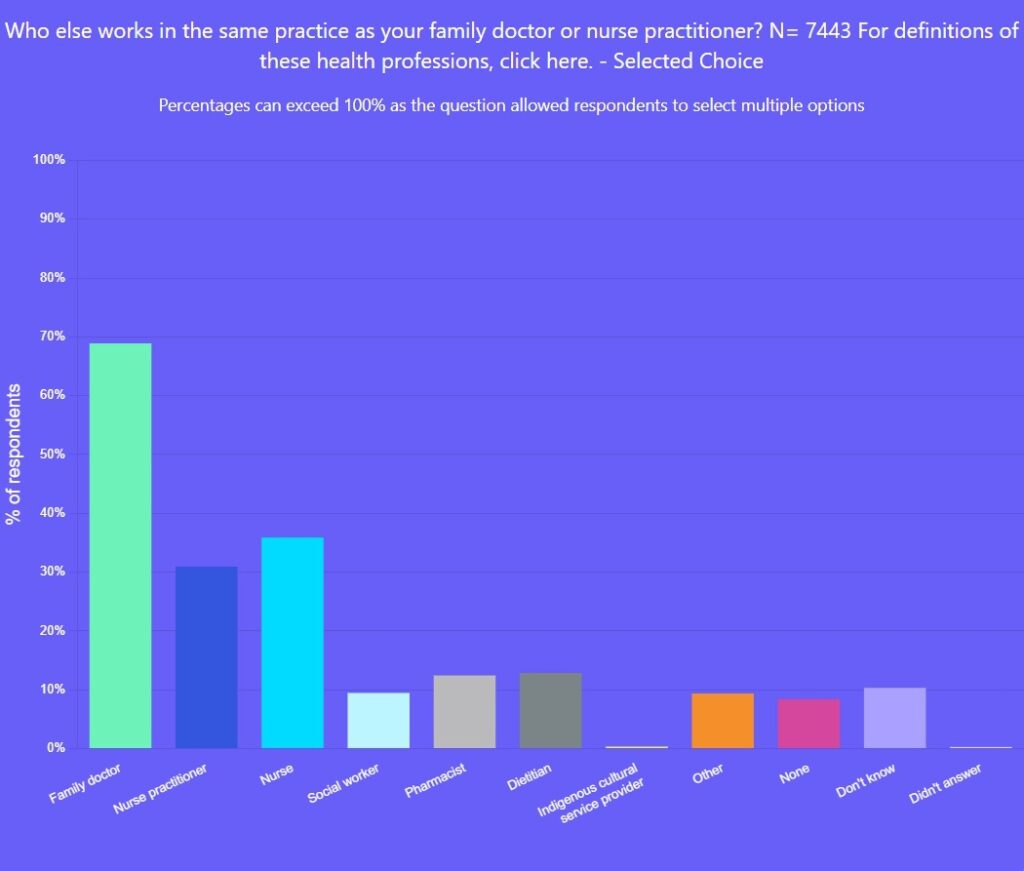

Only 5 per cent of people in Canada reported having an NP as their primary-care clinician and only 31 per cent said their primary-care practice included an NP. Yet, NPs are highly skilled and can be the most responsible primary-care clinician for many individuals. They can work independently or alongside family doctors, often in collaborative models of team-based care.

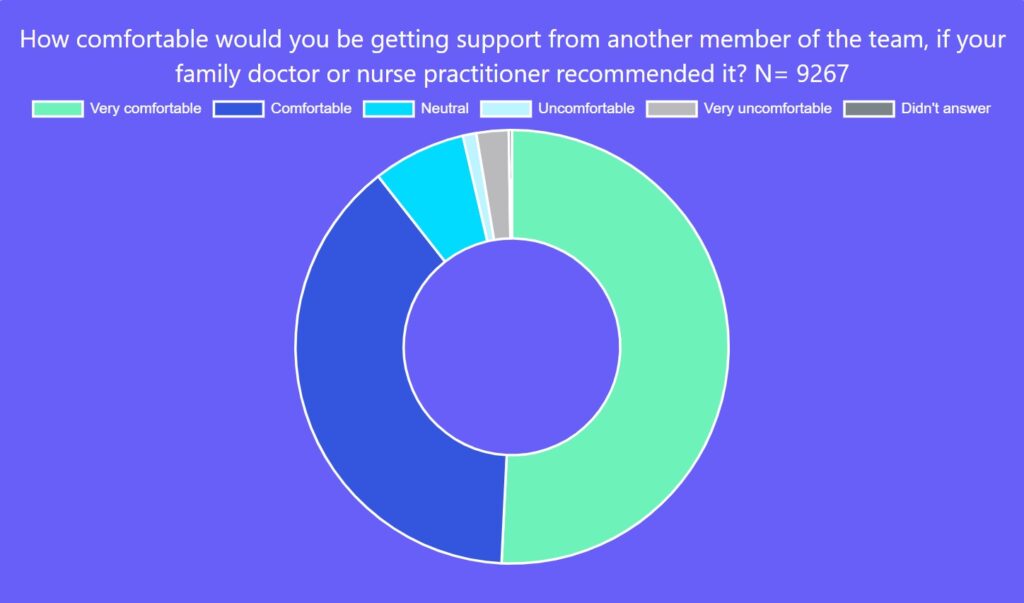

Respondents were overwhelmingly supportive of team-based care. Ninety per cent said they would be comfortable (39 per cent) or very comfortable (51 per cent) getting support from another member of a primary-care team if it was recommended by their family doctor or NP.

How can other team members help? Nurses can provide routine child care, counsel for preventive care and help manage stable chronic conditions. Social workers can provide counselling for mental health and addictions, support system navigation and connect people to community resources that address social needs. Pharmacists can optimize medications, dietitians can provide nutritional advice, and physiotherapists can assess and manage musculoskeletal problems. These are just a few examples of how we can leverage expertise to ensure high-quality care while growing the capacity of family physicians and NPs.

In addition to providing patients with access to health professionals with complementary expertise, teams can enhance care coordination and patient experience. They provide family doctors and NPs with valuable peer support and the ability to share responsibilities for patient care. Not surprisingly, research has demonstrated that team-based primary care can improve health outcomes as well as clinicians’ joy in work. Equitable access to these services is key to ensuring society’s most vulnerable groups reap the benefits of improved health outcomes.

However, the OurCare survey indicated that few people in Canada have access to a robust primary-care team. A minority said they had other health professionals as part of their practice. Thirty-six per cent of respondents who had a family doctor or NP said a nurse was part of the practice, but fewer than 15 per cent said that pharmacists, dieticians or social workers were.

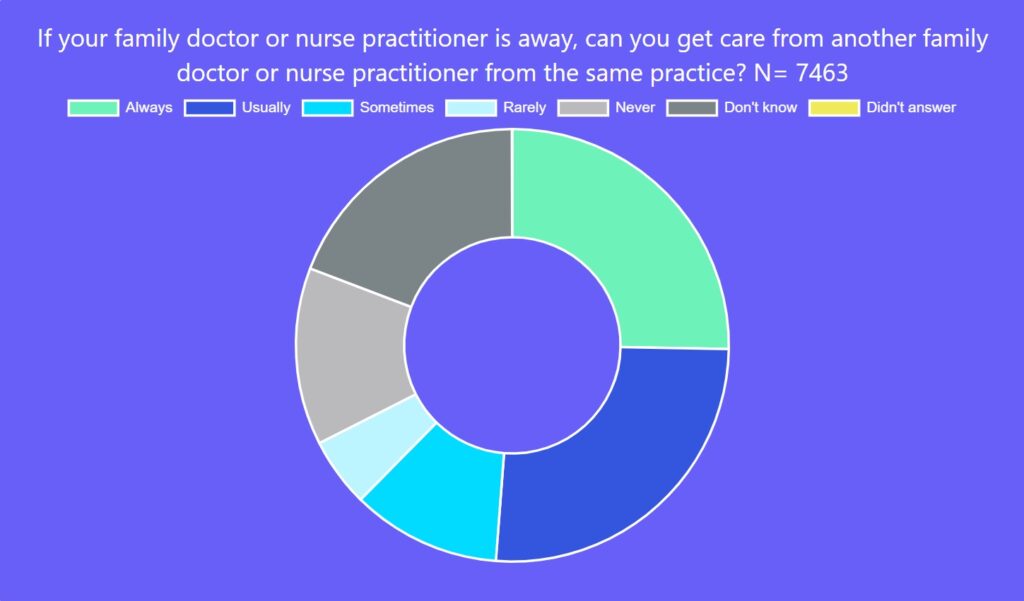

In addition, too few respondents seemed to have a family doctor or NP that belonged to a group that provided cross-coverage when their care providers were away. Only half of those surveyed said they could access another family doctor or NP always (25 per cent) or usually (26 per cent) if their own provider was unavailable – a critical set-up for ensuring timely access for patients while preventing burnout for clinicians.

Group practice seems to also have other benefits for patients. Data from a recent survey of Canadian family physicians found that more physicians in group practice offer weekend appointments, use other personnel to manage chronic conditions, use electronic medical records and offer on-line booking.

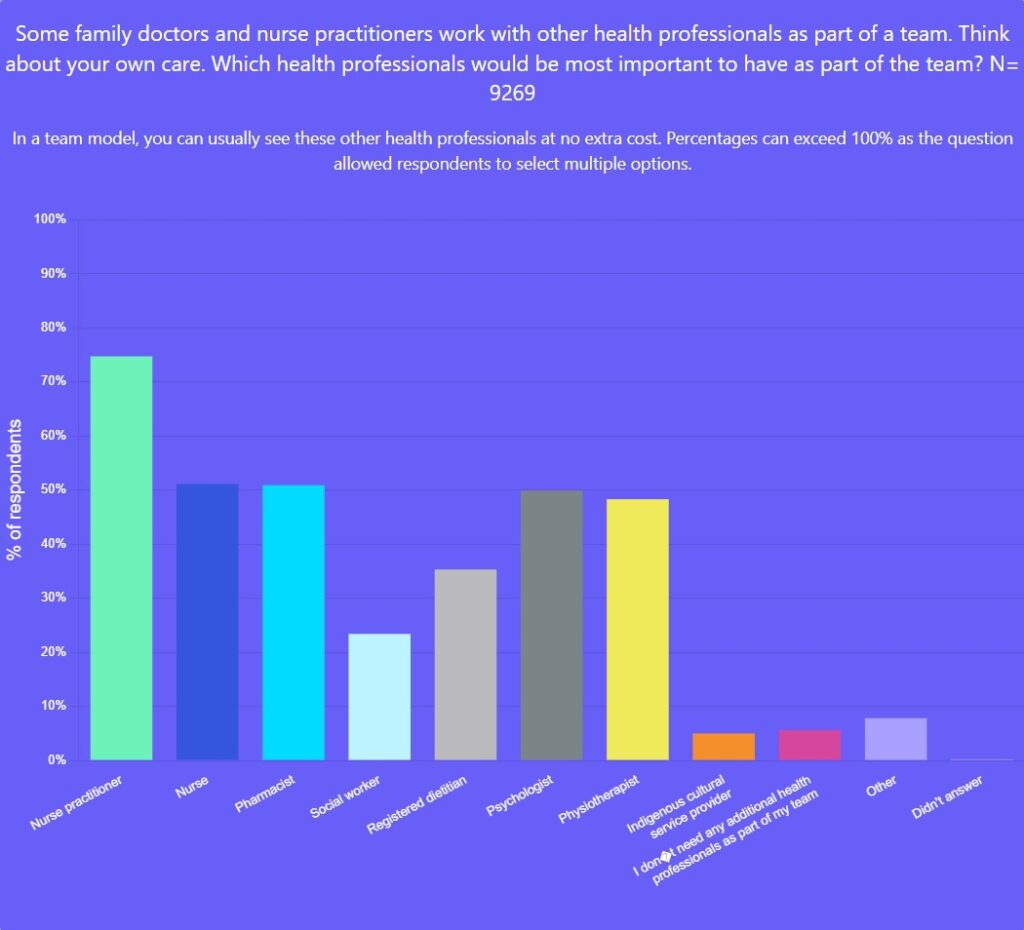

When asked who should be part of a primary-care team in addition to a family doctor, survey respondents most commonly identified the following professions:

- 75 per cent – Nurse Practitioner

- 51 per cent – Nurse

- 51 per cent – Pharmacist

- 50 per cent – Psychologist

- 48 per cent – Physiotherapist

Interprofessional teams are considered a foundational building block of primary care and are endorsed as part of the vision for the Patient’s Medical Home model put forth by the College of Family Physicians Canada. Likewise, the Canadian Nurses Association views interprofessional collaboration as critical to improving access to patient-centered health-care delivery.

Yet, despite this recognition, expansion of team-based care across Canada has been heterogenous, staggered and slow. Ontario is one province that made early progress but even so, less than 30 per cent of Ontarians have access to a primary-care team. Ontario introduced the Family Health Team model in 2005 but paused expansion in 2012, ostensibly due to cost. Ontario’s Community Health Centres have been around for decades but provide family medicine services to less than 2 per cent of the population.

Unfortunately, the population potential of team-based care has not been fully realized in Ontario. The average number of patients cared for per doctor is currently lower in these models than in non-team models. Teams were not initially implemented with the goal of increasing the capacity of family doctors to take on more patients – they need to be re-oriented toward this objective in ways that we know work. And sadly, research has demonstrated that areas with the highest primary care need have the lowest access to team-based care – we need to reverse that.

In the next phase of OurCare, we are conducting in-depth dialogues with everyday people in five provinces across Canada about their priorities and recommendations for primary care. This week, we released the recommendations from the Ontario Priorities Panel. A key recommendation is to move away from solo providers and expand team-based care for all residents of the province.

The three of us, at some point in our careers, have each experienced the joy of practicing primary care as part of a dynamic, supportive team. We’ve reaped the benefits professionally of learning from our colleagues and tackling complex issues with the help of many minds put together. We’ve seen patients reap the benefits of diverse expertise and wrap-around care.

It’s time for all clinicians and patients to reap the same rewards; the OurCare survey tells us people are ready to embrace change. Let’s expand team-based care with the objectives of closing equity gaps and improving clinician capacity to ensure every person in Canada has access to primary care.

Explore the data yourself at data.ourcare.ca. For more information about OurCare, visit OurCare.ca.

The comments section is closed.

Such a well written article that shines a light on the current shortfalls in Primary Health Care while offering solutions that are viable and make sense!

Team-based care works !

I have just released a new book covering this topic . It is called: Dying to be Seen: The Race to Save Medicare in Canada . It is written by a NS nurse.

In my mind the crux of the issue, practically, is this:

1) Simply having a mix of MDs, NPs, and BNs in clinics does not mean that they are a team. Too often these professions prefer to create their fiefdoms and not figure out how to actually SHARE work. There is little incentive to produce the work of functional teams in most healthcare environments: no payment model, no staffing model, no physical structure, and little understanding in patients about what “team” actually means. Even our College hierarchies do not support the concept: in the end, medicolegally, the burden of responsibility for outcomes always stops at the physician. This hierarchy of responsibility is real and supported in our core infrastructure.

2) Teamwork takes collaboration time. In this day of supply and demand imbalance, there is simply none of this without adding hours onto the work day. And collaborative time needs to be structured and focused. It rarely is. We do not have project management plans for our patient care issues as businesses do for customers. We should think differently here.

3) Sadly, going deeper into individual issues usually creates more work. The more you ask the more you learn, and then the more you may feel responsible to fix (if fixing is even possible). Teams, in my experience, create more work per patient, not less. One can certainly argue that this is important and valuable work, but still, it is simply more. Division of responsibility is usually not well planned in healthcare teams.

4) Team-based care also requires tremendous administrative support. Admin staff also need to feel personally responsible for outcomes, not be simple “employees”. In most clinics, in order to save money and maximize revenue for the physician group (often the only source of income for the team), we scrimp on hiring and staff retention. Thus healthcare professionals end up doing more and more admin work/paperwork, and soon reach the point of burnout. Support staff require funding and should be seen as necessary parts of the team, not a cost centre.

5) Patients are rarely included in the team model. And I don’t mean a PFAC, but rather each individual patient. In a perfect team, each patient would have a defined pod of a physician, NP, nurse, social worker, pharmacist, MOA and care navigator. Not all of these would be needed all the time. But overall the team should be accessible and stable in its makeup. Patients derive trust from human relationships and knowing who their caregivers are, building bonds over time. A constantly rotating set of “providers” does them little service, It commoditizes care and keeps it transactional, which leads to more visits, more testing, more repetition and a feeling of being “a cog in the wheel” — for all of us.

6) We must remember that the majority of care to Canadians does not happen in organized and funded FHTs or academic family medicine centres. Team-based care required adaptation for the general community, with solutions created for the 75% (in Ontario; even more in other provinces) of care provision that is not in one of those environments. The solutions for team-based care have to come from that community for them to be relevant. Outside of some very functional FHOs in the community, not funded as teams, this has not been the norm. We need to look further, dig deeper and be more creative.

In my mind, it comes down to this: we have to redefine “team” to be practical and real. We must fund it appropriately beyond provincial health insurance plans. And we have to support providers in all their forms to build solid relationships. Only after we have all this can we get down to being able to look after more people on our rostered lists. Providers, governments, health policy experts and professional associations must work closely together to get this right. We have to start now.

Team based care is being put forth as the panacea for all that ills primary care provision to Ontarians and Canadians. Family physician colleges, medical associations and the media have taken this cause up with little knowledge of how the community based business of primary care works. A large part of why family physicians are leaving community based practice, students are avoiding family practice residencies and graduating family practice residents are not starting family practices is the poor value proposition of being a family physician. A large part of that is poor pay/cuts and sub inflationary increases in pay in the face of business overhead paid by family physicians to run the business.

The team-based panacea does not touch on this. Who pays the overhead and how do physicians get paid in these team-based structures? Current teams have physicians being paid per patient per year while everyone else is on salary with benefits. In addition, only the family physicians pay business overhead while the rest of the team does not (with the exception of community health centres). Current teams are also much more expensive while caring for less patients than traditional community based family practices.

Until these three issues are addressed and the playing field is levelled with regards to method of payment and payment of overhead, any team based models are doomed to be more expensive and utter failures.

I’d love to have a discussion about team-based care some time.

I suspect most family physicians are incorporated and enjoy the opportunities associated with running a business, which does indeed include the burden of overhead. I suggest Family Health Team team clinicians and supports add to the value of the business of primary care, offering FREE assistance to physicians who are paid to see (or not see) their patients. Overhead costs seldom increase and, to my understanding, actually decrease for physicians working as part of a care team. I can’t imagine another business where the government funds free help to serve the existing customer base (patients in this case) and compensates for costs associated with this free help.

I don’t begrudge this free help; In fact I believe it’s the right move and laud it. More tools in the toolbelt if you will. Nurse practitioners, dietitians, mental health professionals, nurses, pharmacists and others added to existing primary care practices represent a strategy to support an aging population, dramatic increases in chronic disease and increased patient demand for accurate information.

I would welcome data to support any position that the cost of family practice has increased because of team-based care as I suspect the opposite to be overwhelmingly true.

Disappointed, again, but not surprised, again, to see the low percentage of respondents who said they’d be comfortable getting care from a social worker if that was recommended by their *physical* health provider.

Some of the care available from a credentialed clinical social worker might be provided by a psychologist, but not all.

I am a retired BSW Hons, trained clinically, but practiced in systems and structures, in substance misuse, for over 20 years. The health care, comprehensive health care, available to people with substance use issues has been, is, and will likely continue to be appalling. The last time I checked, about 10 years ago, there was not a single medical school in Ontario that had a mandatory, core, course in substance use & misuse. Yet we know that the first round of fentanyl addiction was clearly an immediate result of physicians’ lack of knowledge. Addictions workers were instantly aware of the problem–in my community, a substance misuse committee, in cooperation with the local police, formed a Patch-for-Patch program: to receive a renewal on your prescription, you had to return all your used patches in a specific form. Physicians were over-prescribing, renewing too frequently, not monitoring their patients’ use, not educating patients on safe use, or even safe disposal. They had taken information guiding their prescribing practices from drug company reps, not from evidence-based research. The program became law in Ontario–with, of course, physicians having the option of ignoring it. It worked quite well, until Chinese powder fentanyl flooded the country.

Many community-based addictions programs are staffed by social workers–ideally, by experienced graduate BSWs or MSWs. They have moment by moment exposure to the situations of people with substance use problems–which are largely ignored by the larger society, and, appallingly, often by physicians and other physical health care providers.

That knowledge, training, experience, expertise ought to be a mandatory component in every medical practice in the country. The stigma against substance misuse, and therefore of its care providers, continues. And we all experience the damage and death that results.

When does this become unacceptable enough for the health professions to take steps to rectify it?

Well said. I agree entirely.