The COVID vaccine rollout is a litmus test for the learning health system. It requires speed, well-working collaborations with community members and the ability to adjust on the fly as supplies and eligibility requirements change.

Overall, the rollout has had its flaws. We failed to prioritize people in hotspots and essential workers until late April and early May, despite Ontario’s Science Table calling for this strategy in February. The booking process has been time-consuming and difficult, punctuated by confusing eligibility requirements that vary between vaccination centres. We didn’t prioritize pharmacies and other sites in neighbourhoods with high COVID rates. But many of these problems speak to supply and distribution issues and decisions made at the government level.

At the more local level, there have been pockets of excellence: learning health systems in action. In a learning health system, community members and health providers collaborate with researchers on ways to improve the system, the changes are implemented in a way that ensures buy-in, and the interventions are tested and adjusted along the way.

Building trust around vaccines for Indigenous people

One success has been the rollout of Auduzhe Mino Nesewinong – a Place of Healthy Breathing in Anishinaabemowin. The vaccine clinic is the collaboration of four partners – Na-Me-Res, Seventh Generation Midwives Toronto, Well Living House and the Women’s College Hospital Centre for Wise Practices In Indigenous Health – all Toronto-based organizations focused on supporting Indigenous health. The clinic started as a testing and contact-tracing site after health and community workers realized that their Indigenous patients weren’t going to centralized testing centres.

“We were planning on working with institutions to make them safer places,” says Suzanne Shoush, a family physician with St. Michael’s Hospital who helped launch the clinic. “And we thought that with enough support, enough training and partnerships, that everyone would be able to just go into the existing infrastructure.”

But early in the pandemic, many Indigenous people told community workers that they didn’t want to go to a mass COVID centre.

“They were expressing being unable to overcome the mistrust and the fear of losing their dignity when they’re in hospital spaces,” says Shoush. “People who had gone to the testing sites were reporting that they didn’t feel good about their experience, and they wouldn’t go back.”

That doesn’t mean there was overt racist treatment at the testing centre. Simply: you can’t make people feel safe and welcome overnight in a setting where they have been ignored, harmed or otherwise discriminated against.

So the groups pivoted – learning health system-style – and set up their own clinic. Throughout the pandemic, the Auduzhe testing and vaccine clinic provided same-day or next-day contact tracing and testing for all close contacts of a COVID-positive patient – beating the city’s average. As of press time, the clinic had vaccinated thousands of Indigenous adults in Toronto, many who might not otherwise book their shots. It has provided Indigenous-led knowledge circles with the community to build vaccine confidence. In conversations with Indigenous patients, Shoush and others explain the effectiveness and safety of vaccines and quell fears that the vaccines have been fast-tracked.

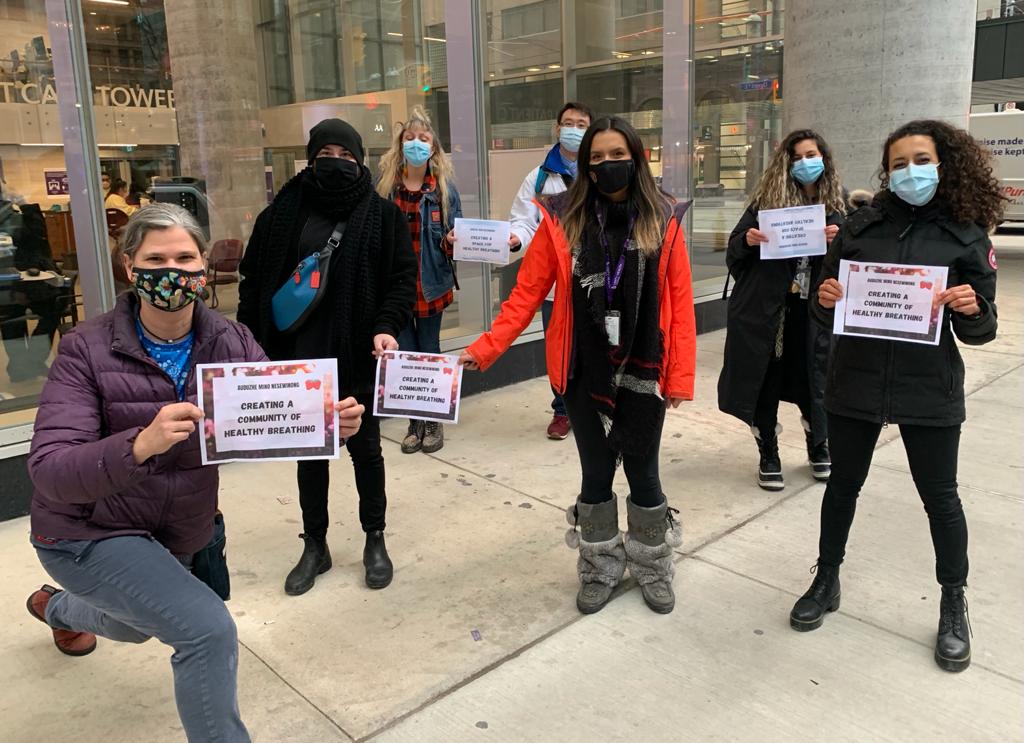

The Auduzhe Mino Nesewinong – a Place of Healthy Breathing - team. Provided.

“I explain (that) Moderna was founded from a grant from Barack Obama during his presidency,” she says. “There’s been research going into mRNA vaccines for decades.”

Building vaccine confidence isn’t just about what is said – people trust the Indigenous health organizations because of their well-established services to the community. Seventh Generation Midwives, for example, has been running a weekly drop-in primary health-care clinic for years.

“We have medicines, we have smudging, we have food, everybody gets a meal, there’s always transportation, there’s always any support that someone needs,” explains Shoush, who works in partnership with Indigenous midwives to provide care.

Meanwhile, the community workers at the Indigenous organizations keep the health providers accountable.

“There are people who give you feedback and keep you in line,” says Shoush. “For instance, they’ll say ‘You’re trying to do too much and it’s causing harm’ or ‘Someone who needed to get a call back didn’t get a call.’”

While informal feedback can be key to a rapidly learning health system, it requires an organizational culture where people feel that expressing concerns will lead to positive change.

Learning on the fly: Pop-up vaccine clinics

Pop-up sites throughout the city have been another shining example of a fast-learning health system.

The seeds for the success of East Toronto’s vaccine pop ups were planted in January, when Michael Garron Hospital collaborated with community organizations, including The Neighbourhood Organization in Thorncliffe and the Flemingdon Health Centre, on virtual town halls. Community leaders and members were invited to ask questions about the vaccines, from safety in pregnancy to side-effect risks. Then, they were encouraged to share what they learned with their networks after the town hall.

“The information was coming from trusted community ambassadors and trusted community physicians, not just Phil from the hospital who they don’t know,” explains Philip Anthony, a registered nurse at Michael Garron who has been so successful at leading pop-up vaccine clinic efforts in East Toronto that he’s been invited to help run pop-ups throughout the city.

The hospital and community organizations have now run pop-up clinics at more than 100 locations, including plazas, residential buildings and mosque parking lots. They’ve been reiterating as they go along. The first day, after seeing people line up for hours, Anthony went home and printed numbered vaccine cards, with an hour-long time slot, that workers handed out in the morning so that people could return at their time slot instead of waiting in line.

Vaccination clinic in the Thorncliffe neighbourhood. Source: Canadian Council of Muslim Women.

“It’s long established … that to reach these vulnerable communities, we need to remove barriers,” explains Wolf Klassen, vice president of program support at Michael Garron Hospital. “People for whom English is not their first language, or who don’t have access to the internet at home, could find it quite challenging to book an appointment.”

As with Auduzhe Mino Nesewinong, the people running the pop-up sites were able to be responsive and adaptable because of deep connections with communities, whose members not only relayed information about needs – which buildings to target, what safety questions to address – but also helped with implementing programs.

Esel Panlaqui, manager of community development and special projects at The Neighbourhood Organization worked with the organization’s 23 community ambassadors to get the word out about the pop-ups. For pop-ups in residential buildings, community ambassadors pre-registered residents and had them sign consent forms in the days before the clinic to speed vaccination when the time came.

Community ambassadors don’t just encourage their neighbours to get vaccines – for the past year, they’ve been helping people get access to laptops for virtual school, food programs and more.

“That building of trust was made even outside COVID,” said Panlaqui.

The relationships allow for on-the-fly creative solutions. At the end of the third day of a pop-up outside of a South Asian grocery store, the line had dwindled but a few hundred vaccines were left. Panlaqui contacted the property manager of nearby high-rises, who had the vaccine pop-up location announced on public address systems, encouraging residents to get their vaccine that afternoon.

There have been, however, some hiccups. Catherine Yu, a family physician and interim board chair of East Toronto Family Practice Network, was part of the team that coordinated the East Toronto pop-ups. She says that shortly after a high-rise building for a vaccine clinic was selected, the team heard about angry social media messages. “My WhatsApp was dinging. There was huge outrage.”

People complained that the building was chosen because of personal connections and that the decision was racist since other buildings with higher percentages of racialized people weren’t chosen. The team had selected the site because data showed that its residents had the highest rates of COVID. (Yu notes that could be because the residents were more likely to go for testing). After the backlash, the team set up some clinics in additional buildings. However, the building that had been chosen based on high COVID rates ran out of supply while there were leftover vaccines at other buildings.

“It was a painful experience,” says Yu. She notes that putting a clinic in the parking lot of the selected residence but opening it to all community members would have been better.

In learning health systems, mistakes are expected – they inform future decisions.

“You have to learn to not be paralyzed … the risk that the reputations of myself or some of the community leaders will be hurt, that’s a small risk compared to the risks of making a slow decision where hundreds or thousands of lives are actually affected because we’ve hummed and hawed and had not had the courage to just make that decision,” says Yu.

Learning health systems are about trying things and recognizing something that community organizers and leaders have known for years, that “speed is more important than perfection,” says Yu. Often, improvements only happen through that trial-and-error process.

As Shoush says, the reason the Call Auntie hotline and Auduzhe Mino Nesewinong testing and vaccine clinic have been so successful comes down to the driven community leaders, health providers and social workers behind it.

“It’s people who get shit done, and I don’t know how to say that without a swear word in it.”

The comments section is closed.