Seniors with dementia in several long-term care homes and hospitals in Prince Edward Island could marvel at the celestial frescoes of the Sistine Chapel, explore the Amazon Rainforest or make contact with a herd of curious, tawny elk in the western United States. But most often, they’d prefer going down to the local post office, the farmhouses where they raised their families and the wharf where they used to fish.

These seniors are among a growing number of elderly people with dementia across Canada who are using virtual reality to escape the social isolation caused not only by their neurodegenerative disorders, but also by the lockdowns that have largely quashed communal life in long-term care (LTC) homes during the pandemic. Caregivers and researchers hope that LTC residents who visit lifelike simulations of meaningful places from their pasts will recall old memories not yet motheaten by dementia, causing them to feel a sense of wistful joy, a swell of pride and to open up to others.

Some LTC homes across Canada have rolled out or scaled up virtual-reality programming because of how COVID-19 led “everything (to) just shut down in long-term care drastically,” says Susan Zorz, director of operations at the Glebe Centre, a non-profit LTC home in Ottawa. The stringency of the restrictions has varied from one LTC home to another, but many have barred visitors and some in hard-hit cities like Toronto and Montreal have largely confined residents to their rooms for months. This intense isolation appears to have worsened symptoms of dementia, precipitating memory loss and provoking more agitated outbursts and other disruptive behaviours. Virtual reality has been “really important” because it has allowed residents to enjoy themselves while maintaining physical distancing, says Zorz.

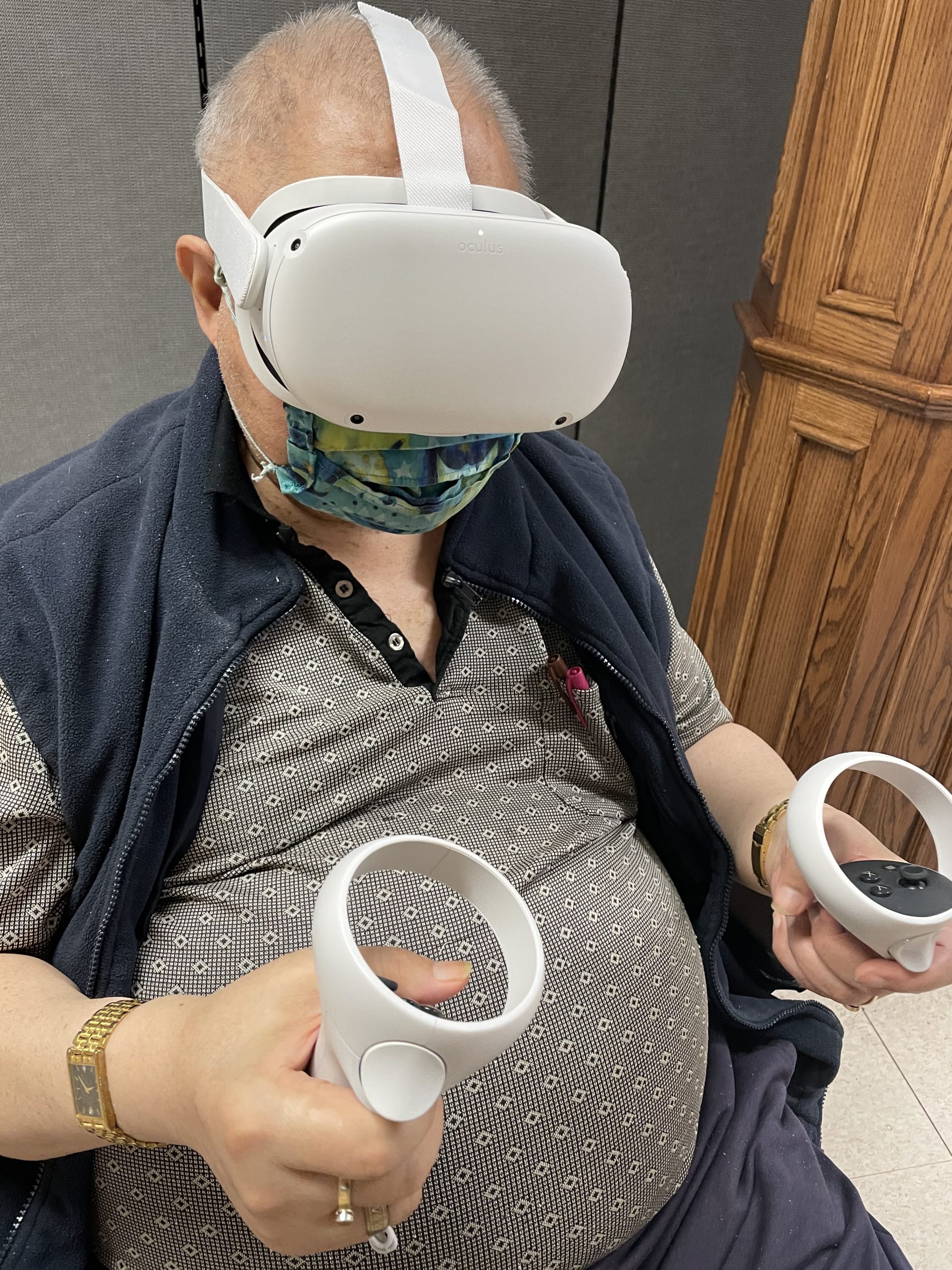

When using virtual reality, residents don headsets – goggle-like screens strapped around the head – that take them inside vivid, three-dimensional worlds. Depending on what platform an LTC home is using, residents will usually have access to a panoply of fun or relaxing experiences, including site-seeing tours, playing with frolicking puppies and guided meditation on a beach. Residents with dementia also undergo reminiscence therapy, in which caregivers use mnemonic prompts, traditionally photographs and music, to remind these seniors of their pasts. Using virtual reality for reminiscence therapy is quite novel, and it often entails using platforms like Google Earth VR to teleport people to three-dimensional reconstructions of places recorded on Google Street View.

Proponents of reminiscence therapy argue that it is beneficial in part because it gives seniors with dementia, who can be quite apathetic and withdrawn, “an experience to share, something to reflect on,” says Jennifer Campos, a psychologist and tier-two Canada Research Chair in Multisensory Integration and Aging at the University of Toronto. When reminded of old memories, residents will ideally speak about them with others, developing relationships that improve their quality of life. “The magic really happens when the headset is removed,” says Kyle Rand, the CEO and co-founder of Rendever, a Boston-based company that has sold its platform to more than 50 communities in Canada.

There has been barely any research into the effectiveness of using virtual reality to deliver reminiscence therapy, but the prospect of it is “promising,” says Lora Appel, a research scientist at University Health Network’s OpenLab in Toronto. Appel and Campos collaborated on a feasibility study published in January 2020 that concluded it was safe and practical to expose elderly adults with dementia to virtual reality for a range of therapeutic purposes, including administering reminiscence therapy. One Japanese study published in December 2020 suggested that using virtual reality for reminiscence therapy improved some dimensions of cognitive functioning and increased morale, “which may enhance patients’ well-being.”

A resident at a long-term care home in Toronto operated by the Rekai Centres wears a virtual-reality headset. (Photo courtesy of Kayla Johnston).

Since it is relatively easy to customize virtual-reality experiences, the technology also seems to align with a broader “paradigm shift” in the field of dementia care: health-care professionals are making more of an effort to involve people with early-stage dementia and their caregivers in creating their care plans, says Appel. This broader movement was part of the impetus for her and her research team to partner with the Toronto Public Library and launch a pilot project last year called the VRchive. The original plan had to be substantially reworked due to the pandemic, but it would have recruited adults with early-stage dementia to collaborate with family and friends on constructing individually tailored virtual-reality scenarios that they could later use as “a trigger for lucidity” when their dementia worsened. Rendever is also looking into making its virtual-reality programming more interactive and customizable through a program it is studying called “virtual family engagement.” During the study, people with dementia in LTC homes have been wearing virtual-reality headsets to meet with avatars representing their family members, who are at home using their own virtual-reality headsets. These avatars sit next to each other on a couch in a virtual living room and face a television that shows old photos and home videos that have been preselected by the family member. Ron Beleno, a prominent advocate of using innovative technology for dementia care, predicts that these sorts of shared experiences represent the field’s future.

In the meantime, staff at Canadian LTC homes are reporting that seniors with dementia are, for the most part, enjoying virtual reality. Two staff members at the Rekai Centres, a non-profit that operates two LTC homes in downtown Toronto, recounted how one man from Malaysia felt “proud” upon visiting his hometown, while another “amazed” resident from India pointed out the grocery store where he had gone shopping and the school his children had attended. Sometimes, the homecoming is bittersweet, however: One woman “broke down crying” when she came upon the front door of her former home in eastern Europe after not seeing it for 40 years, says Barbara Michalik, director of community and academic partnerships and programs at the Rekai Centres.

The Glebe Centre acquired the Rendever platform during the pandemic last year. Before then, it had been using BikeAround: Residents would mount a stationary bike and pedal down virtual streets projected from Google Street View onto a large, domed screen in front of them. Zorz recalls how one woman would bike through Arnprior, a town west of Ottawa, before her dementia became too severe. She would bike to her house and recall memories revolving around her husband – fishing with him along the Ottawa River, the times he shovelled their large driveway in the winter. “She got to go home in her own mind,” says Zorz.

For seniors with dementia, these sorts of experiences are “a validation of who they are as a person,” Zorz says. “Who are we but not for our memories? To be able to talk about and share our life story is really important, especially for our older adults here.”

For LTC residents who “feel trapped, either within the confines of the centre or within their minds,” reminiscing through virtual reality “brings them back and connects them to part of who they were,” says Paul Young, an administrator at Health PEI who brought virtual reality to LTC homes and hospitals on the Island. “There’s a tremendous amount of joy that comes from that.”

The comments section is closed.