Kate Mulligan is no stranger to trying to balance her work and home lives.

With her three young daughters thrown into a world of online schooling during the pandemic, working as an assistant professor at the University of Toronto and a member of the Toronto Board of Health looked much different for Mulligan, who traded in the lecture hall for the living room and board meetings for Zoom meetings.

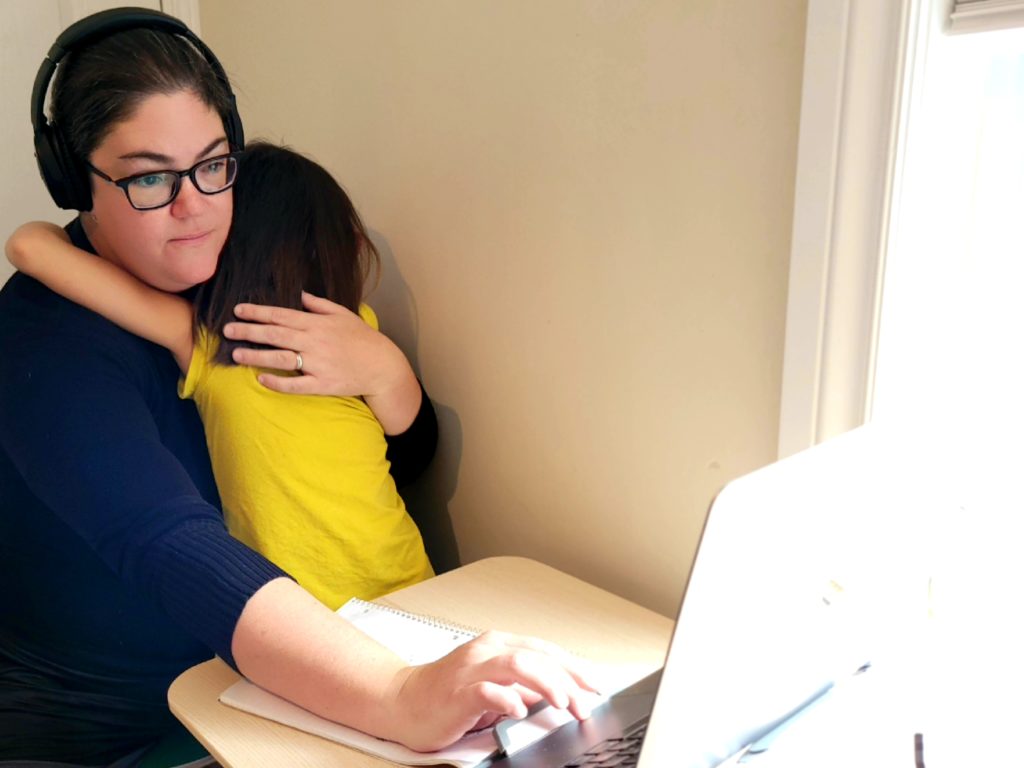

“It was hard on my three girls to be home in one of the longest lockdowns in the entire world, to have my eldest in virtual school, and for my husband to be sitting between our six-year-olds trying to help them do Grade 1 French immersion,” says Mulligan. “I’d say every 15 to 20 minutes, I would be holding a crying child (from) a little conflict or stubbed toe or something.”

Initially trained in geography, Mulligan says she has always been interested in “why we have differences in health outcomes” across varying parts of the world. Working as an intern in Queen’s Park, she was exposed to reports that concluded Ontarians living in the north were expected to live shorter lives than those in the south. Mulligan says she “couldn’t believe that there were such differences in our own province.”

This motivated her to return to school for a doctorate in health geography, which she says was unexpected since she “didn’t think I had an interest in health.”

But, “Poverty By Postal Code’ by United Way came out at that same time and I was just really captivated by that,” says Mulligan.

As for her involvement with Toronto’s board of health, Mulligan says she wanted to bring a voice from the public to board meetings and use the knowledge she had acquired as a health geographer and professor to raise issues she says are vital to Toronto, such as race-based data.

Mulligan says the province didn’t collect this type of data early in the pandemic because it believed everyone should be cared for equally. However, she says this wasn’t an appropriate public health approach.

“One size doesn’t fit all,” says Mulligan. “We do need to have different approaches for different people and different populations, which is sometimes called targeted universalism. We have a broad approach, but we need to target the communities and people who need it most.”

With marginalized communities taking a significant hit from COVID-19, Mulligan says tracking race-based data was one of the most important topics she discussed, and she worked closely with Pillars of the Pandemic winners Cheryl Prescod and Angela Robertson.

“Those are the people I needed to listen to,” says Mulligan. “The leaders coming from communities with significant expertise, trust … knowledge, building relationships, but not enough resources to do what they needed to do and not enough autonomy to do what they needed to do, especially early on.”

She adds that her main role with community leaders was to be an icebreaker – “to help remove the barriers so that they can do what they do so well.”

“They tell me what the barriers are, then I go off and try to help take some of them down , and then they can go off and do the work,” says Mulligan. “I wouldn’t be able to do any of what I do without strong leadership in the community.”

Mulligan posts items from the board’s COVID-19 debates and discussions online because it’s vital to make information more accessible to the public, she says.

“It can be kind of arcane to understand the procedures and how to get involved, so this is just making it accessible, making it something that’s for all of us,” she says. “Without it, we really cannot have a public health system that will weather the next storm.”

One size doesn’t fit all.

Mulligan says it’s also important to be transparent about workplace COVID-19 outbreaks and works closely with board chair Joe Cressy to do so.

With a child or two – and sometimes all three – by her side during her time working at home, Mulligan says being on the board hasn’t been easy. She says she often felt torn as someone who loves being both a parent and an advocate.

“I had that feeling for a little while that was like, if I wasn’t the one doing it, it wouldn’t happen, which isn’t true,” she says. “I urge all advocates to remember that we’re doing this together.”

She adds that toward September, she started feeling the “moral injury” of trying to make work happen and witnessing decisions that she didn’t believe were the right ones. However, as a self-proclaimed optimist, she says she tried to remember that even the smallest step can lead to a larger one if advocates stick together.

Provided by Kate Mulligan.

But she still had her doubts at times. “I thought if I’m feeling that I’m neglecting my children, (then) I’m not having an impact,” she says. “And (if) my trust in institutions, which is never super strong, is weakened even more, I might need to step back.”

So she did.

Mulligan took a brief hiatus from her work to refocus and has since returned, feeling better than ever about being an advocate, she says. The main thing she’s learned, she adds, is that although larger structures and organizations are “capable of changing faster than we think, it doesn’t mean they always will.” It’s the communities, she says, that need to be heard more often.

“Communities know what’s right for communities. Given the right set of resources and infrastructures and supports, they can and should be taking leadership.”

This profile was published as part of the Pillars of the Pandemic series – brought to you by the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and Closing the Gap Healthcare. We will release new profiles in the coming weeks, with 13 people being honoured in total.

The comments section is closed.