Sharon Straus’s interest in caring for the elderly started when she was young.

Straus, geriatrician, clinical epidemiologist, physician-in-chief and director of the Knowledge Translation Program for St. Michael’s Hospital, recalls being first inspired by her great-grandfather, a veteran of the First World War.

She remembers visiting him in his residence when she was young, hearing his stories and his life experiences – and witnessing how he and other residents lived with chronic disease.

She says it was then that she became mindful of the quality and nature of elderly care.

“It had always kind of stuck with me from that age and so when I went into medicine … I did my subspecialty in geriatric medicine,” says Straus, who notes that she and her sister were the first in their family to go to university.

“What I really loved about geriatrics was the holistic approach to the individual,” she says. “That it looks at the entire individual from health status and the social situation to their family and caregiver situation. I really like that comprehensive and holistic look at an individual because I think it really reflects how we, as a society, really need to think about caring for people … And I think the pandemic has highlighted that even further.”

Part of what makes the current situation problematic is that these issues are long-standing, says Straus.

She notes the pandemic created an opportunity to address the “crisis” in care – an opportunity Straus wanted to seize upon as part of her latest role as a member of the Royal Society of Canada’s COVID-19 Task Force.

In June 2020, Straus, who is on the Royal Society of Canada COVID-19 Task Force, helped put together a 60-page report titled “COVID-19 and The Future of Long-Term Care” that included recommendations to redesign Canada’s long-term care sector.

“It wasn’t that we were identifying new issues. All the issues that we identified in that report were well known. There have been hundreds of reports that have been done, there have been many inquiries and commissions into long-term care in Canada … The pandemic, though, really shone a light on this even further, and identified where we had all this evidence,” says Straus.

“I just hope that it does lead to lasting change and that we do see the recommendations that we outlined getting implemented. Because I think there’s always a risk that attention shifts to other things … But I think that the pressure is on all of us, as a society, to maintain that pressure and to make sure that we don’t lose momentum.”

“It wasn’t that we were identifying new issues … there have been hundreds of reports that have been done.”

Straus notes that it has been a privilege to collaborate with experts in the Royal Society of Canada’s working groups. In addition to the working group on how the health-care system will recover, she is starting another group on post-pandemic recovery from a research perspective.

The theme of recovery is an important one, says Straus – it highlights the need for change and improvement.

“This is our opportunity to really push ahead and think about what long-term care should look like. What are the models of care that would adequately meet the residents’ needs? What are the needs for supporting the essential care partners?” says Straus. “I think this is an opportunity for us to really think about that and make sure that this has been a period of disruption. Good things can happen out of disruption.”

One of these “good things” is learning the importance of knowledge translation, or using evidence to inform action and protocol.

Straus, as physician-in-chief at St. Michael’s Hospital, led the group responsible for developing the physician-care model for the COVID-19 inpatient units. She says she was fortunate to have access to infectious disease specialists modeling COVID-19 information in a way that would inform the team’s approach to care.

“That was kind of one of our big lessons – always use evidence to inform everything that we do. Leverage everybody’s expertise … As long as you’ve got a plan for the worst-case scenario, then I think that’s when you feel prepared,” says Straus.

“I felt a lot of anger, a lot of frustration, a lot of sadness.”

Despite “planning for the worst and hoping for the best,” Straus notes that there were moments when she felt tired and frustrated.

“If anybody says that there were times when they weren’t frustrated over the past year, I think that they might not be speaking the truth,” says Straus with a laugh. “There were lots and lots of times of frustration for sure. Like right from the beginning, thinking about PPE access … or really thinking about frustration around what we were seeing happening in long-term care homes. That was a lot. I felt a lot of anger, a lot of frustration, a lot of sadness.”

More recently though, particularly with the vaccine rollout, she says she feels hopeful. As from the first day of the pandemic, Straus says she continues to be appreciative of the role of her co-workers.

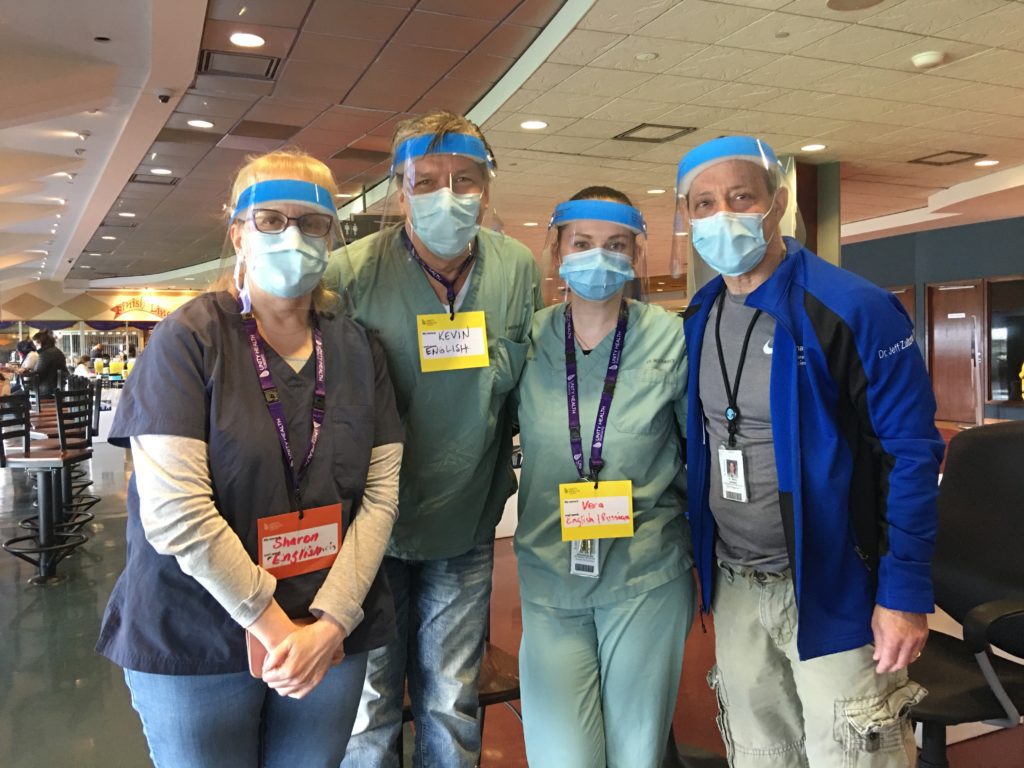

Provided by Dr. Sharon Straus. With colleagues from Unity Health Toronto at a pop-up vaccine clinic.

“I always tell everybody that I feel incredibly privileged. I honestly do believe I have the best job in the world … It’s been an interesting year. It’s been a challenging year, but the people that I get to work with every single day, and the fact that I can come to work every single day and interact with these individuals, and interact with patients, and interact on the research side with so many fantastic people, (it) has just been really a true, true privilege,” says Straus.

“So, it’s all of their work that should be recognized rather than mine. Because they are the ones that have been doing this fantastic work again and again and again.”

This is the first release in the Pillars of the Pandemic series – brought to you by the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and Closing the Gap Healthcare. We will release a new profiles in the coming weeks, with 13 people being honoured in total.

The comments section is closed.