They were in the trauma room when the picture was taken: Jennifer Wilson, outgoing president of Uxbridge Health Centre, standing with her hand on the shoulder of colleague Carlye Jensen, chief of the Uxbridge site of Markham-Stouffville Hospital.

Wilson admits they looked really tired, really serious, really concerned. Still, though, it is one of her favourite pictures.

Taken at the start of the pandemic, it serves as a reminder to both Wilson and Jensen of just how much they have already accomplished in leading their small community of Uxbridge, Ont., through a major crisis.

“I remember thinking when we took that picture, ‘We can do this. We are going to get through this. And we are going to do everything we can to protect this community,’” says Wilson. “I always say I’m braver when Carlye and I tackle something together.”

Provided by Dr. Wilson and Dr. Jensen and depicted in the painting featured in this story.

As skilled doctors cross-trained in family and emergency medicine and with established family, personal lives and commitments to the town, Wilson and Jensen became reliable and valued founts of information about COVID-19 in a period marked by uncertainty, mistrust and misinformation.

“Public health, when they speak to our people without that level of trust, there’s only so much buy-in, especially when you’re dealing with a pandemic where everything’s changing every day,” says Wilson.

“What we quickly realized is our patients wanted to know what we thought because of that level of trust. They know us. We’ve spent our whole careers here. We’ve raised our families here. Our community members see us in the emergency room and in the office, but they also see us at the park and in the hockey arena and everywhere else in town.”

Their roles of providing information to their community started with parents reaching out for advice, connecting with families through local Facebook groups.

“People would personally message me (asking), ‘Well, what are you doing with your kids?’ Or ‘How are you handling this?’” says Jensen. “And so, I would just (respond), here’s what I am seeing and here’s what I’m doing, not as a doctor but as a community member, as a parent, as a wife, as someone who’s trying to live through this pandemic … And then it became clear that everybody seems to want this practical information.”

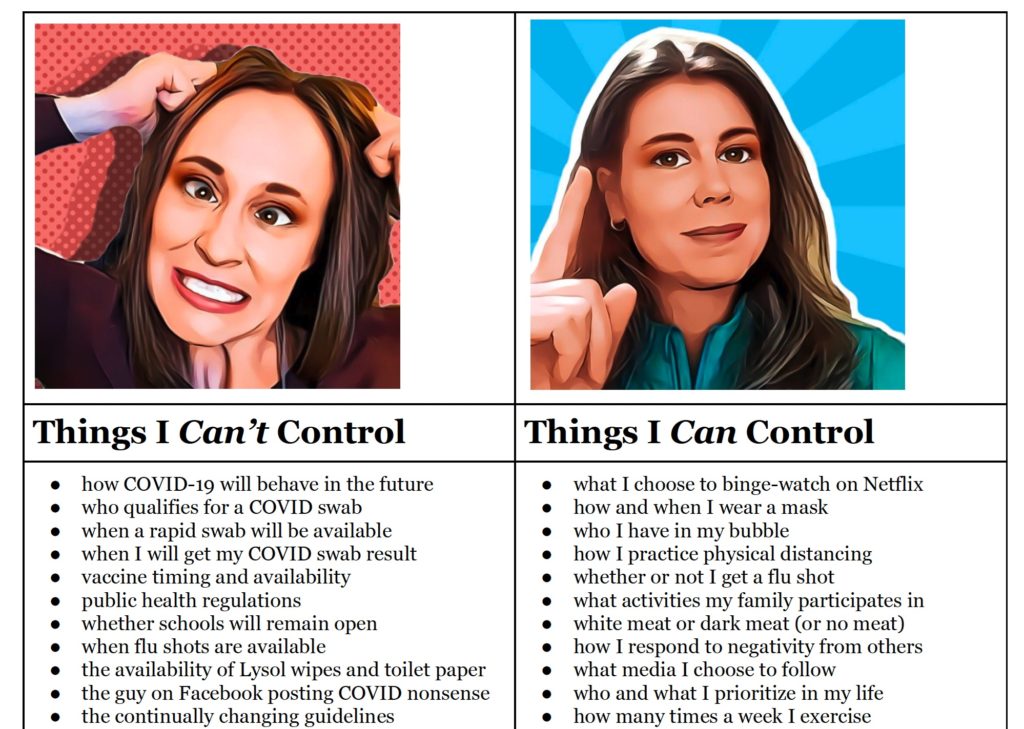

To help guide their community through “muddy water,” they launched a newsletter on March 9, 2020. Since then, they have produced 22 newsletters, with their circulation spreading rapidly, picked up and distributed by their local Canadian Tire, minor hockey association, grocery stores and retirement homes.

Wilson says that part of what made their newsletter appealing is the way in which both physicians were in tune with the community’s needs, deploying a conversational, personal tone in their writing – something that allowed them to highlight a range of complex issues.

Some of their topics have included “Top 10 Tips to ‘flatten the curve’ of COVID-19 in Our Community”; “Tips for Making the Most of an Extended March Break”; “When and How to Get Care”; “Learning to Dance in the Rain”; “5 Pillars to Guide our Re-entry”; “COVID-19 Myth Busters”; and “Why We Got the COVID-19 Vaccine (And Why We think You Should, Too)” – all showered with a range of personal anecdotes along with science, data and professional perspectives.

“It was exactly what our town seemed to need at that moment in time,” says Wilson. “Carlye and I fell into this role. I don’t even remember Carlye and I talking about it. I don’t remember us sitting down and saying, ‘This is how we’re going to handle the pandemic’… It just sort of happened because I was being asked, Carlye was being asked, and we quickly recognized the need for a trusted voice, even though we might not be experts in all things.”

That is part of small-town medicine, notes Jensen. Rural doctors become generalists who are focused on a unique style of care – one that follows patients from “cradle to grave.”

“It allows for this type of care that is so cohesive and seamless between the different environments. And that’s why I love doing rural practice,” says Jensen. “You get this great ability to do comprehensive care … When I’m in my office, looking after someone, I know what probably happened while they were in hospital because I do that work as well.”

While Wilson grew up in Uxbridge, moving back permanently 21 years ago, Jensen relocated to the town of 21,000 in 2007, a move she says required some adjustment.

Part of the challenge, particularly for those who are not from small towns, is the issue of boundaries, explains Wilson. She notes that when you live and work in the same community, it can sometimes lead to tough situations in which doctors often feel they are “on duty all the time.”

Rural doctors become generalists who are focused on a unique style of care – one that follows patients from “cradle to grave.”

“It’s not for everyone. We’ve had great doctors who just can’t do it,” says Wilson. “But I have to say our community … for the most part, when they see us in the supermarket, or they see us at church, or they see us outside of the medical setting, our community is quite protective of us and they let us be moms and spouses and just people. Because otherwise it’s pretty hard to sustain.”

She says that while the boundary issue has been exacerbated by the pandemic – it now being more difficult to “turn off” work – they say small-town living has also given them the benefit of community support.

“We’re in a privileged position from a burnout standpoint,” says Jensen. “Not to say that I wasn’t also fearful and that I wasn’t also feeling stressed (with) everything going on, but I found the process a bit energizing, if anything … People offered to drop off food on my doorstep, quite literally, to help me through this. Family members tried to help offload my child-care situation to open me up to help in the way that I was trained to do in the medical sphere.”

Wilson agrees that the community really stepped up. She notes that it is still shocking to think about how their medical advice had an impact on so many people and their decision-making.

Just recently at a vaccine clinic at their office, Wilson was talking with a few people who were expressing their excitement over the town’s high vaccination rates.

“Then three of them said, ‘Well, you and Carlye told us to go out and get our vaccinations and when you tell us what to do, we listen,’” says Wilson. “I mean, I don’t know who they were, where they lived in town, but somehow the message was getting out.”

Both doctors say that Uxbridge can serve an example of the power of the local health professional and how they can play important roles as facilitators.

“Family practice does indeed have a lot to offer in these scenarios,” says Jensen, who says that their small newsletter even reached beyond their region, with their insights appearing in local papers.

“I hope public health pays attention to this, to the power of the family physician, especially in a small town. When things like this happen, we are uniquely positioned to help communities because we have relationships, we have trust,” says Wilson.

“Turning to the family physician in times of public health crisis like this is very, very natural and yet it’s not always appreciated or utilized in the way it could be.”

This is a part of the Pillars of the Pandemic series – brought to you by the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and Closing the Gap Healthcare. We will release new profiles in the coming weeks, with 13 people being honoured in total.

The comments section is closed.