Adrienne* started living with her (now ex-) husband at the age of 17. By 19, she had made her first big purchase – a new car. That’s when the abuse started. At the time, she was working two jobs but found that money always came up short when paying the bills. When she discovered that her husband had spent her earnings, he told her that her car would be ‘repossessed in a month’ if she left and that she would ‘never make it out there without him.’ She felt trapped.

Her ex-husband’s use of money to control her began to escalate in other ways. Despite spending money on himself, Adrienne’s husband would tell her ‘we can’t afford that’ when she wanted to make a personal purchase. Even for an inexpensive beauty product, he questioned her. ‘Why would you buy that? It’s not going to make you look better,’ she recalls him saying. In her words, “if someone is capable of financially abusing another person…they are capable of far worse things…he tore me down emotionally, mentally, and financially.”

Adrienne’s friend, who worked for an abuse hotline, recognized what was happening when she met Adrienne’s husband for the first time. She waited until Adrienne was alone and then offered her assistance. ‘When you’re ready, I’ll help you leave,’ Adrienne remembers her saying. But it was denial, fear, shame, and feeling like she “failed as a woman” if she got divorced, which stopped her. When the abuse worsened to the point where her husband sexually assaulted her at gunpoint, she knew she had to leave. Three weeks later, Adrienne left her husband. By then, “it was no longer about money, if I stayed he would have killed me,” she says.

Unfortunately, Adrienne’s situation is all too common. And it has a name. Financial abuse. When money is used to control a person’s ability to access, acquire, and maintain their own financial independence, it’s known as financial or economic abuse. Before an abuser escalates to other forms of abuse – emotional, verbal, physical, or sexual – financial abuse can be the first sign of domestic violence.

Financial abuse can be subtle, and so it is less commonly acknowledged in the public and medical communities. According to the 2018 National Poll on Domestic Violence and Financial Abuse, 78% of the American public has never heard of financial abuse in relationships. As the least recognized form of abuse, there is a need for greater awareness in the public and healthcare sectors to the same degree as other forms of abuse.

According to Lieran Docherty, program manager of the Woman Abuse Council of Toronto (WomanACT), there is limited Canadian data on financial abuse in intimate partner violence cases. Most research that exists focuses on elder financial abuse, despite its prevalence in up to 99% of domestic violence survivors.

Financial abuse is only recently entering the mainstream narrative. Celebrities including Serena Williams, Kerry Washington, and Suze Orman are raising public awareness of this under recognized form of abuse.

The Difficulty in Recognizing Financial Abuse

Although both men and women experience abuse, women are four times more likely to be affected than men, with transgender women and women with disabilities at higher risk. While we know abuse can happen in same-sex relationships, it is unclear what proportion includes financial abuse. Financial abuse also cuts across all races and income levels, affecting households with incomes ranging from $25,000 to $150,000.

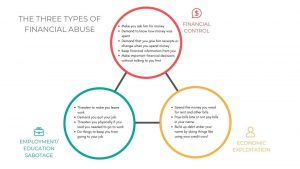

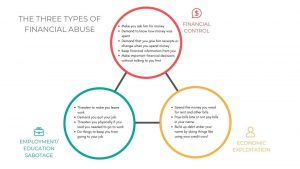

Financial abuse often begins subtly, perhaps appearing as considerate gestures to pay bills, casual requests to borrow money, or reassuring statements like “let me handle the finances since you’re under a lot of stress.” Slowly, it can escalate until the abuser controls every bank account, credit card, and pay cheque. With damaged credit, decreased income, and/or lacking recent work experience, victims face barriers being independent – like renting an apartment, affording childcare, or finding and maintaining employment.

These economic repercussions of financial abuse are the main reason why a victim might stay or return to an abusive partner. According to an anonymous survivor from Virginia, she stayed with her husband because she only had $50 to her name and couldn’t afford to leave. “I wanted to go home to visit my family and he wouldn’t allow it. He only transferred enough money for me to pay the bills,” she says, “I ended up doing small cash backs from groceries until I had enough to go back home.”

But abuse doesn’t only affect people of limited means. Career women and higher household earners can also find themselves exploited for financial gain – whether it was supporting a partner’s high spending habits or being coerced into funding a partner’s business. For Brittany*, a survivor from Oregon, she ended up over $10,000 in debt because she was made to feel guilty for earning an income. “I was in a verbally and mentally abusive relationship, which I later realized was financially abusive…I bought [everything]…all groceries, paid all utilities, electrical, cable, phone bills.”

According to Docherty, recognizing financial abuse is challenging in part due to traditional gender roles and societal norms around money. The patriarchal role of men as the breadwinner and women as caregiver for children can normalize and conceal financial abuse. Financially controlling tactics or arguments around family finances may be dismissed as “just the way things are.”

The Three Types of Financial Abuse: Adapted from the Scale of Economic Abuse (SEA-12)

Finances are often not talked about in daily conversation. “Because there’s such a taboo around speaking about finances and income with those outside your household, it’s difficult to identify what abusive behaviour is. We don’t talk about those behaviours with our friends and family outside the relationship,” Docherty adds.

Financial abuse shows up in a myriad of ways and is not as obvious as a bruise or insult, says Judy Postmus, associate dean of social work at Rutgers University. Some victims may not even recognize they have been financially abused until after experiencing other forms of abuse.

“The word ‘abuse’ is stigmatized in all cultures,” she says. “Nobody wants to think they’re a victim, nobody wants to think that a loved one is abusing me. It’s easier to recognize if there’s physical violence involved and people will say ‘but he never hit me, does that mean I’m a victim?’”

Postmus also points out that in her research on financial abuse, “women would say ‘I never knew he could abuse me in this way.’” She adds that often, it takes the intervention of an outsider or friend to show the victim what’s been going on.

Financial abuse can also extend to children within the relationship. Child support, or tax benefits intended to support a child, may also be withheld by the abuser even if they no longer have custody, adds Docherty.

“I started working at a grocery store and any money I made from there (and before), my dad would keep,” says Ada*, who was victimized by her father as a teenager. “He didn’t set up bank accounts for us and instead ‘invested’ [our earnings] into his business.”

Why do providers not routinely screen for financial abuse?

Education and public awareness about financial abuse in domestic relationships is another reason why healthcare providers might underestimate its prevalence, says Dave Wheler, assistant professor at the University of Toronto Department of Family Medicine, “I don’t think I’ve come across many CME [Continuing Medical Education] or articles on it. You don’t see headlines of financial abuse situations.”

Wheler also teaches the medical school curriculum on domestic violence, which consists of a single seminar where financial abuse is covered, but “it’s difficult to teach the specifics of that form of abuse” he says. “It almost gets lost in other forms of abuse.” For healthcare providers who graduated earlier, they had even less teaching on domestic violence, let alone financial abuse.

Financial abuse is also underreported by patients. “I’ve never had a patient come in specifically for financial abuse,” Wheler says, “and if they do, it’s for more visceral types of abuse – physical, sexual…” For this reason, it’s difficult for researchers to collect data on it, he adds. In the emergency room, screening tools also focus on the visceral forms of abuse. Victims who present to the ER with signs of distress may not be screened for abuse if there are no physical or overt markers, but may be experiencing financial abuse.

“For a lot of survivors, they will tell their family and friends first and healthcare professions, they tell last – unless they’re directly asked,” says Postmus. She emphasizes that providers don’t always ask, but it is important to do so.

When asked why she did not talk to her healthcare provider about financial abuse, Adrienne says, “I’ve never been asked by a provider if money is an issue,” says Adrienne. “But I think money is how a lot of abusers control their victims.”

In the privacy of a clinic, saying “I routinely ask all my patients this question,” then asking “do you have trouble making ends meet?” and “do you have access to your own money?” might make a difference, Postmus suggests. Providers can also put infographics and pamphlets in their waiting room to increase awareness of financial abuse and open the conversation of what a healthy relationship looks like before offering resources.

Comfort with managing financial abuse may be another reason why providers are hesitant to screen for it. “As a practicing family doctor, what can we do about it?” Wheler asks. “Anytime we do any screening, unless you can change the outcome, we don’t feel comfortable dealing with it.”

He adds that previously, doctors weren’t taught to screen for abuse in part due to the lack of interventions. However, “now screening is becoming more appropriate because there are more effective resources.”

According to Docherty, educating victims about the Domestic and Sexual Violence Leave is one way healthcare providers can help. Depending on the province, victims are allowed up to five days of job-protected paid leave that is independent from other types of leaves, such as for sickness. Providers can assist by notifying employers if a victim is uncomfortable asking for this leave herself. Furthermore, providers can support victims in accessing dental care, hygiene products, and prescriptions, areas directly impacted by financial abuse.

In the United States, the Security and Financial Empowerment (SAFE) Act is a similar policy but not all states have leaves for domestic violence victims.

What do you do if you or someone you know is at risk?

If you or someone you know is experiencing financial abuse, the first step is to be connected with resources to help navigate and understand this form of coercive control, says Postmus. She recommends calling the National Domestic Violence Hotline in the US. In Canada the Assaulted Women’s Helpline can connect people affected by financial abuse to local resources that can help them learn how to protect themselves financially.

Postmus also suggests having a financial safety plan. This might include knowing how to safely save enough money, setting up direct deposit of your pay cheque, keeping records of financial documents, passwords and PINs, knowing your credit score, and what assets you have access to or not.

There are programs and organizations that empower women through financial education. Postmus says that the Purple Purse financial curriculum is a good place to start. “It takes a standard financial literacy curriculum and adds in a layer of how to protect yourself financially and what to do in a safety plan.”

Docherty adds that “when a woman is at greatest risk, it’s when she’s planning to leave.” Victims can evade detection by placing copies of financial documents or cash in a separate location. Taking photos or writing down your possessions along with the age of the item can assist the courts in appraising the value of an item or giving the victim access to her property, should she leave the home, says Postmus.

“There’s still a lot to be done,” says Docherty, “starting with financial literacy education at an early age, learning about healthy relationships, policies around increasing [governmental] emergency funds, recognizing that poor credit rating or debt is as a result of the abusive relationship, and offer credit repair alternatives to help her rebuild her economic security much quicker.”

For Adrienne, Instagram has become a community that motivates her as she documents her journey out of debt. She follows the #debtfreecommunity (over 765 000 posts), and it helped educate and motivate her to achieve financial independence.

Having left the abusive relationship 13 years ago, she acknowledges that “not everyone has a story like mine.” With the help of her friend, she was empowered to confront her abuser and move out. Unfortunately, she recognizes that doesn’t happen for all women or intimate partners.

“I do believe if you can identify someone being abused in one way, there are [probably] other ways they are being abused,” she says

She would like to acknowledge Adrienne (@life.after.bankruptcy), Ada (@adafern), Brittany (@budget_thislife), and the numerous anonymous survivors who shared their stories with her.

*The last names have been removed to maintain anonymity of the survivors featured in this story.

The comments section is closed.