“When we came to Canada as refugees, I was nine and my sister was three.”

“I remember going through the airports and my parents talking to border officials. No one was explaining anything to us. But children observe. I remember witnessing my parents, who didn’t know the system, trying to navigate it. They spoke English with an accent. I remember seeing somebody being unkind to my father, seeing people’s judgements and prejudices. I remember the effect that had on me, the effect on my sibling, the effect on us as a family for the rest of the day. And sometimes I would see the exact opposite, the incredible kindness in how someone treated us.”

“Those experiences I had contributed to my decision to go to medical school.”

I wanted to be one of those people that a child might be witnessing, being kind to their parent.

“I was born in Bangladesh. My mother was a university professor in social welfare. My father was a civil servant but for most of my life, he wasn’t able to work. He suffered from schizophrenia and PTSD related to the war of independence for Bangladesh in 1971. At that time, he was working with the government, and somebody from the opposing military came and rounded everybody up in the place where he worked. They were going to shoot everyone by firing squad. And then one of his friends called someone. He knew somebody who knew somebody, so they were able to escape. But only my father and a few folks were spared. He never talked about it. I don’t know what he witnessed.”

“On the trip here, my dad wasn’t doing well, he was weak. But we got a family doctor very soon after arriving. They found colon cancer and he had the surgery and he recovered well and we never thought about it again. Had we remained in Bangladesh, he could have died, not from any political turmoil but from his colon cancer.”

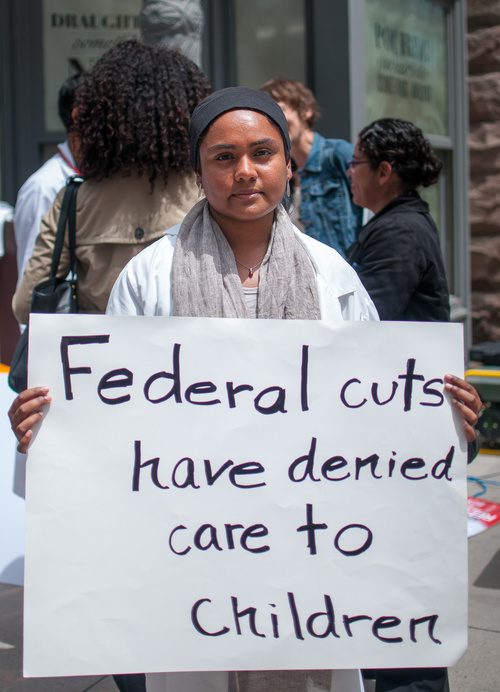

It’s really upsetting to think that the people who are arriving now are not being given that same chance that we were.

“Some refugees aren’t covered for health care at all. I advocate for access to health care for refugees, in demonstrations and through letters to politicians and in any way I can.”

“My patients are here at the clinic for half an hour in a month. After they leave this clinic, they have to go buy groceries. They have to figure out how to pay rent, or if they can afford these medications or not. They have to prioritize if their children are getting fruits and vegetables. There are so many things going on in the rest of the 30 days. We’re just a blip in people’s lives.”

“If we focus all our attention on that half hour blip and forget about the rest of it, we’re not going to improve outcomes for people.”

“It really bothers me when health providers say ‘My patient won’t adhere to their medication and I’ve said everything I can, and they just don’t do it.'”

I think, if your goal is to improve this patient’s health, then you have to work harder.

“You have to figure out what’s going on with them.”

“But I’ve also had times where I’ve been frustrated, and I made it about myself. I once had a client who had a really severe respiratory illness and we needed her to see a specialist and get some tests. But she didn’t have social supports and she was dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder from her childhood. She had severe social phobia and agoraphobia and she wasn’t able to sit through an appointment with someone she didn’t trust. It’s always hard to watch someone really struggle and to feel kind of useless. Finally, after much convincing, she was on board and ready to go. When I saw her the week after, I had gotten a no-show slip from the specialist. I couldn’t stop myself. The first thing I said to her, I think even before hello, is ‘How come you didn’t go to your appointment?’ It was painful for her to hear that accusatory tone from me. She felt so much pressure as it was. She had to walk out. That stayed with me for months. We eventually worked things out and she’s doing better now. But I still feel bad that I did what I tell other providers not to do when it comes to my patients.”

“When I write a letter for a patient, I will explain ‘This person is a survivor of a residential school.’ Or, ‘This person is experiencing trauma from war in their country of origin.’ I try to translate their story, because I don’t want others to make judgements, or to make everything the patient’s fault and forget about the other factors.”

I don’t think western medicine takes into account culture very well.

“There are patterns that I pick up in particular cultural groups that don’t fit medical labels. I have a patient of Portuguese descent and every time we meet, he has this melancholy kind of nostalgia for a time that was and it’s a big part of every encounter that we have. I am about to travel to Portugal and I read a travel book and found out this entity actually has a name. This sad nostalgia is a very common Portuguese way of expressing the human experience and connecting with someone. People who are not aware might label it as depression or adjustment disorder after immigration. In medicine, we learn to categorize things. But somewhere along the way, the human being that we’re interacting with can get lost.”

The comments section is closed.