“Safe supply!” “Or we die!” “Safe supply!” “Or we die!”

Eris Nyx leads a call and response at the final stop in a protest march through Vancouver’s downtown eastside. Behind her, volunteers fire up barbecue grills outside a venue where a local band begins to set up – an almost celebratory end to a demonstration weighted with grief.

The group of about 150 people, including several peer advocacy groups, wound through the neighbourhood on April 14, marking six years since the B.C. government first declared the overdose crisis a public health emergency.

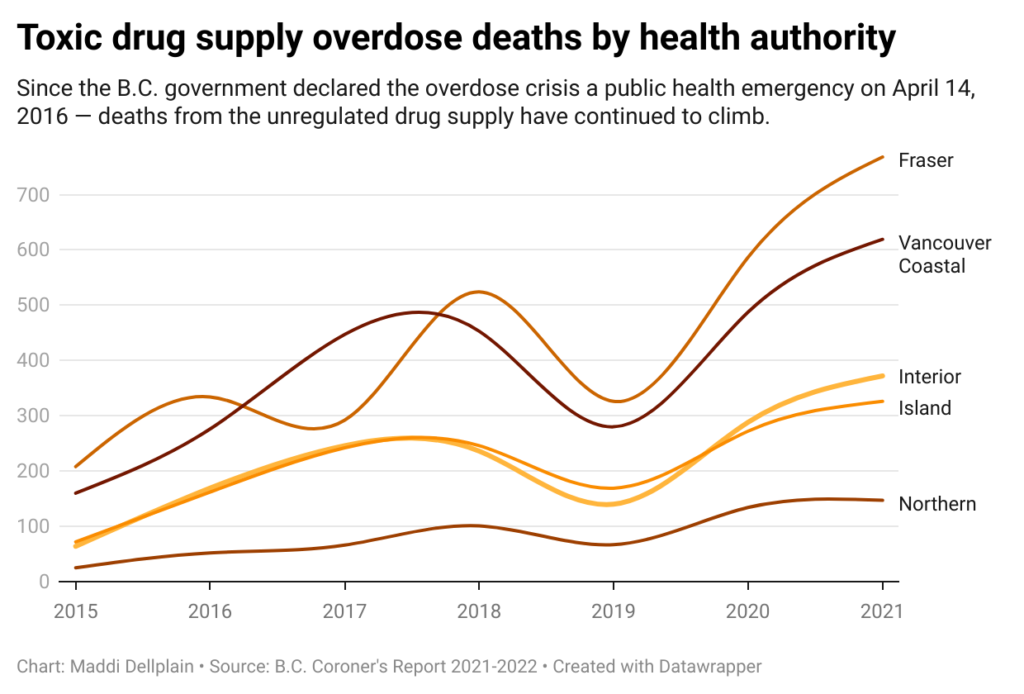

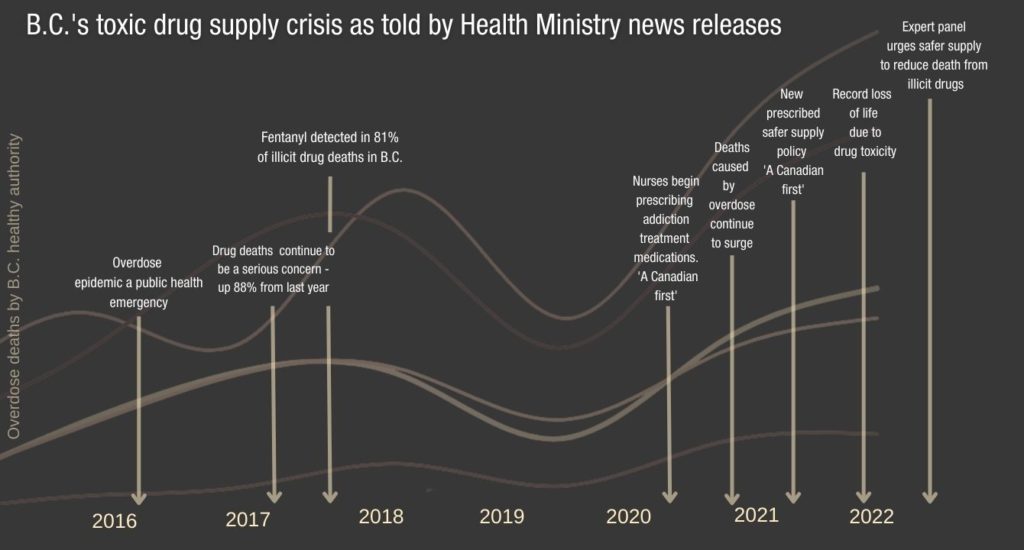

Over the past year, the province has touted several policy changes aimed at addressing the crisis, such as additional funding for existing federal safe supply projects and authorizing nurses to prescribe addiction treatment medications. But deaths from drug-related poisoning continue to surge.

Organizers say that prescription-based safe supply options aren’t reaching enough people and the model isn’t able to address the magnitude of the crisis. “All I can tell you is that as someone who uses drugs, we are no further ahead now than we were at the start of the declaration of the public health emergency,” says Nyx, who is the co-founder of the Drug User Liberation Front (DULF), a peer-led group leading the charge for a more accessible safe supply model.

“The term safe supply has gotten so muddled. When you say ‘safe supply,’ people think prescriber-based solutions to the crisis. What we need at the end of the day is the regulation of the drug market,” says Nyx.

Over the past year, DULF has been fighting for federal sanctioning to run something they call the DULF Fulfilment Centre and Compassion Club.

If DULF is able to run a small pilot compassion club, it would be the first peer-led organization of its kind for currently illegal substances. But compassion clubs as a form of civil disobedience are not new.

In the 1990’s, marijuana compassion clubs operated illegally, providing medicines to AIDS patients. Their earliest iterations, like the B.C. Compassion Club Society, began (and still operate) as community-driven nonprofits. “The parallels are very similar in the sense that they’re both health-focused initiatives with the ancillary benefits of building community and educating communities about how to take care of themselves,” says Donald MacPherson, executive director of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition.

A B.C. Centre on Substance Use (BCCSU) report describes heroin compassion clubs as a cooperative model that provides safe access to medicines and connects members to other health services. It posits that compassion clubs could help reduce overdose-related deaths and decrease drug-related crime.

Eris Nyx speaks to the crowd gathered for the sixth anniversary of the declaration of the overdose crisis as a public health emergency. The event was organized by the Coalition of Peers Dismantling the Drug War in partnership with peer groups, DULF and the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU).

Last April, DULF gave away free half-gram boxes of clearly-labeled heroin, methamphetamine and cocaine to people who use drugs in Vancouver’s downtown eastside in the first of three protest events that year. This month, DULF expanded its action by sending 14 grams of tested drugs to other peer groups across the province to distribute in their respective communities.

DULF doesn’t profit off any of their giveaways and so far no charges have been filed against the group. “I think we’d have to be substantially bigger than what we are now for (law enforcement) to care,” Nyx says “At the point that they would care, I’m hoping we would have enough evidence that it becomes legal, and then it would be a non-issue.”

But for now, without certain protections, DULF could still come under legal penalty for violating the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA). DULF applied for a federal exemption to the CDSA in August 2021, a legal shield often granted to other harm reduction services, like overdose prevention sites. But it still hasn’t received a response from Health Canada. DULF says it will continue to push ahead despite being at risk.

The giveaways are designed to demonstrate a simple principle: When people know exactly what they’re taking, they don’t die of accidental overdose.

Conservative estimates indicate that 83,000 people in the province are at risk for opioid overdose. This figure does not include those who use other drugs, like stimulants, or who would not meet the criteria for an opioid use disorder, like those who use drugs recreationally. It is unclear how many people are at risk across the country, but from 2016 to September 2021, nearly 27,000 people died from drug toxicity in Canada.

Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Sheila Malcolmson has said that 12,000 B.C. residents have been prescribed “safe supply.” But other reports suggest that this figure doesn’t distinguish between medications designed mainly for those who wish taper or stop use (like opioid agonist therapies) and pharmaceutical alternatives to illicit drugs. This figure likely represents those given short-term prescriptions for withdrawal management under the Risk Mitigation Guidelines (RMG) at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Other public health experts say true pharmaceutical alternatives – like slow-release morphine, fentanyl and sufentanil – are primarily available through existing federally funded safe supply projects, and that only about 500 residents have been able to access them. When asked about the discrepancies in numbers, Malcolmson did not reply directly, but said in a statement to The Tyee, “I have heard from prescribers, care providers and people with lived experience, and I agree – expanding safer supply is a vital step to reduce deaths from toxic drugs. That’s why we have expanded our program.”

However, because B.C.’s safe supply policies stem primarily from the RMG and operate within a prescriber-based framework, those wishing to access still encounter a number of other barriers. Many prescribers aren’t willing to prescribe safe supply, and without the express support of regulatory bodies like the B.C. College of Physicians and Surgeons, physicians may rightfully feel at-risk for doing so. For those who are able to find a willing prescriber, they may lose their prescription if they also access street drugs.

The prescription alternatives on offer also may not meet the needs of many drug users. A survey released by the SAFER Victoria Initiative found that participants would be more likely to access safe supply if the right dose and drug were available, with options that reflect what they’re taking on the street and are “easily accessible without a lot of hoops to jump through.”

SAFER is a flexible, prescriber-based program that currently supports about 110 people through active case management and is one of several federally funded projects across the country. “People need to be able to go to a medical clinic sometimes and that’s OK,” SAFER clinical nurse educator Corey Ranger said at a safer supply panel earlier this month. “But people also need to be able to access drugs at a dispensary and make their own decisions.”

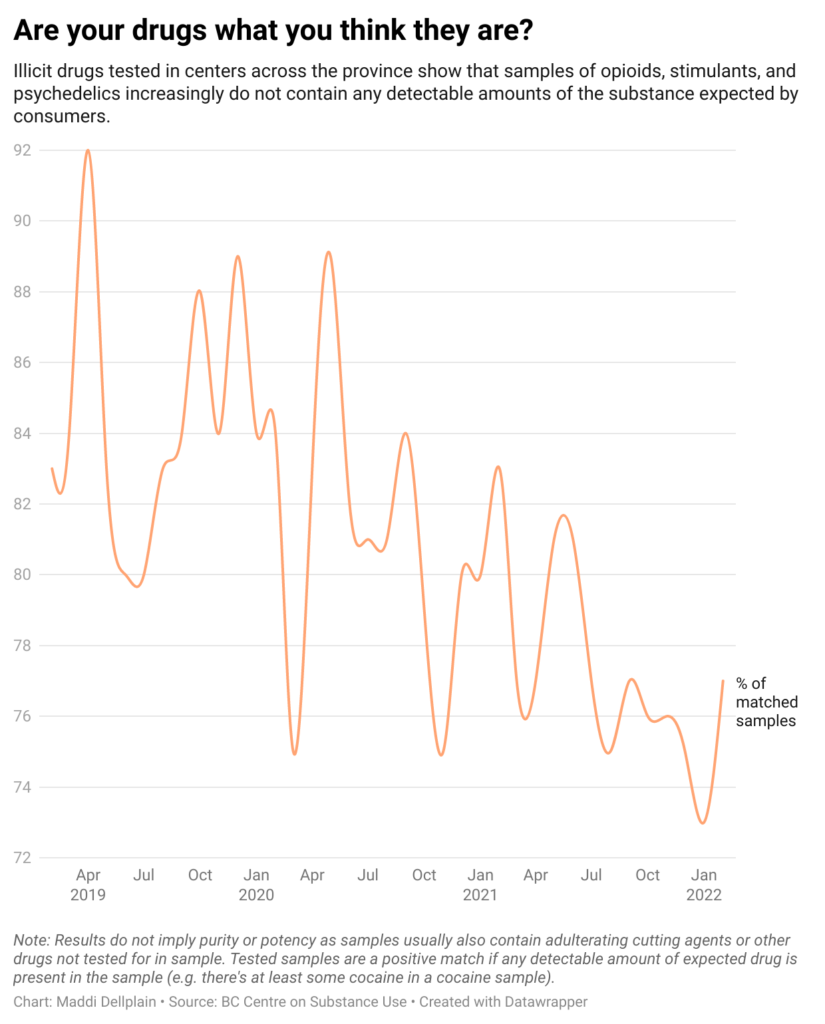

Over the past three years, drugs obtained from the illicit market have become increasingly unpredictable. One BCCSU report shows that only 73 per cent of the drugs tested in January actually contained the drug that the client expected in any detectable amount.

What has been found in the drug supply is also concerning. “The main issues in the opioid supply (is the presence of) carfentanil, benzos and quantifying fentanyl,” says DULF co-founder Jeremy Kalicum.

In February, 38 per cent of the opioids tested contained benzodiazepines, but BCCSU drug checking reports say that this is likely an underestimate. Etizolam, the most common benzodiazepine found in the unregulated opioid supply, is often missed by current drug-checking technologies.

The presence of benzodiazepines in the opioid supply, or benzo-dope, makes it more lethal by complicating overdose response.

Illicit opioids are also becoming much more potent. As of 2022, 91 per cent of illicit opioid samples contain fentanyl – the ultra-potent synthetic opioid that has been the primary driver of fatal overdoses. But Nyx says it’s not necessarily fentanyl itself that’s the issue, it’s that people don’t know how much of it they’re using.

DULF tests its drugs through Substance at the University of Victoria using a testing technology called paper spray mass spectrometry, a method that can more accurately quantify the amount of fentanyl in a sample than most widely available options like FTIR testing and immunoassay strips.

Kalicum says that generally speaking, the most accurate drug-testing technologies available like mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) are designed for laboratory settings. This means they are very expensive and require a high-level of expertise to operate. Right now, he says that chemists at Substance are developing their own technologies to try to make these higher-level testing services more affordable for community drug-checking purposes.

For now, the more widely available FTIR testing can only measure fentanyl within a 5 per cent margin. This could mean up to a 50 per cent difference in potency. “That’s huge,” Kalicum says, “The government (has been using drug checking) to pass the buck to say ‘we’re doing something,’ but it’s not scalable.”

Nyx adds that it can take up to a day to get results back from most walk-in drug testing services at clinics, non-profits or mail-in services – longer than many people are willing to wait. She says that compassion clubs could increase capacity by checking drugs in bulk, shifting the responsibility of testing away from the individual. The model would work a bit like a consumer protection initiative “like the (Food and Drugs Act) for narcotics.”

Other smaller long-term safe supply studies like NAOMI and SALOME have shown that when participants were given a dependable supply of safe drugs, they reported improved mental and physical health and a decrease in criminal activity related to drug-seeking. SAFER Victoria has likewise found improvements in the lives of its participants and a decrease in harms linked to the unregulated supply.

Nyx expects compassion clubs will also have a positive impact on people’s lives, but first it has to be tested.

“At the giveaways, we can’t yield long-term data.” She says she hopes to do a longer-term evaluation soon, with the goal of supporting 10 to 15 participants’ entire drug supply. But running even a small project will be difficult without federal support. Without a Section 56 exemption, DULF will still be at legal risk and companies that could readily provide DULF with a supply of clean, pharmaceutical-grade drugs will be reluctant to do so, leaving DULF confined to the illicit market.

MacPherson says DULF’s work is reminiscent of the early days of Insite, North America’s first safe injection site based out of Vancouver; and a possible projection of the long road ahead. “Just getting one injection site was six years of advocacy work, and it’s a tiny intervention. That’s constantly the problem with any innovation, getting it to scale,” says MacPherson, “But that’s not to argue against doing it – this is absolutely what we have to do.”

Ranger says that though there is no one “silver bullet” that will end the overdose crisis, he urges the government to take a “less myopic” approach to harm reduction.

“They’re focusing on 10 per cent, the medical pilot studies – and we’re figuring some things out. But the majority of people who use drugs don’t need to see a doctor. What they need is the right to choose and to know what they’re getting when they get it.”

The comments section is closed.

Most opioid addicts were addicts before they started using opioids. My friend has been using marijuana and other drugs since she was 14. She was prescribed opioids for carpal tunnel syndrome though she has never touched a computer. She and a couple of her friends with the same problem are patients of the same doctor who has a couple of clinics catering to drug addicts. Yes addiction is a problem but most people by now know drugs are addictive.