As the oncology grand rounds audience settled, I handed envelopes to attendees with instructions not to open them until the end of the lecture. The contents of the envelopes would seal their fates – among them, three would be cured, three would be hurt, one would die, and many others would be subjected to invasive follow-up procedures and long-term worries. Such are the benefits, and risks, of low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) lung-cancer screening.

Globally, lung cancer is the No. 1 killer among cancers. In 2022, an estimated 30,000 Canadians were diagnosed with the disease, and 20,700 were expected to die from it. Based on data from 2015 to 2017, only 19 per cent of men and 26 per cent of women diagnosed with lung cancer survived beyond five years.

However, the earlier that lung cancer is diagnosed, the better the chance of survival. Five-year survival rates range from 66 per cent for lung cancer that has not spread (Stage I) and drops precipitously to about 3 per cent for lung cancer that has spread to other parts of the body (Stage 4).

Unfortunately, most lung cancers – about 70 per cent – are diagnosed when the cancer has already spread. It is sobering that this percentage has only marginally improved over the last few decades. It was reported to be 79 per cent in a 1998 Alberta study. For comparison, only 18 per cent of breast cancers are diagnosed when the cancer has spread beyond a few lymph nodes.

A number of lung-cancer screening strategies have been tried, and failed, including chest X-ray and sputum cytology (looking for lung-cancer cells in spit).

Screening high-risk patients with LDCT has shown promise. The first of a series of reports linked to the landmark American multi-centre National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) was published in 2011 and demonstrated reduced lung-cancer death rates in those screened using LDCT.

The NLST enrolled more than 50,000 participants aged 55 to 74 who had smoked the equivalent of at least a pack a day for 30 years and were either current smokers or had quit within the last 15 years. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either conventional care plus a chest X-ray or three annual LDCT screens. The LDCT group experienced a 20 per cent relative risk reduction in lung-cancer deaths and a 6.7 per cent reduction in deaths of any cause. A 20 per cent reduction sounds impressive but it needs to be considered alongside the absolute risk reduction. Accounting for variable follow-up times among the more than 50,000 participants, there were only 62 fewer cancer deaths in the LDCT group after three years of screening.

In 2016, the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care put the NLST results into perspective.

Based on the NLST protocol, the estimated that out of 1,000 people screened, three fewer will die of lung cancer; three others will have major complications from invasive testing such as lung biopsies; one will die of such complications. In addition, 351 people will have a positive LDCT scan and will be subjected to additional invasive procedures or serial follow-up imaging only to find out, ultimately, that they do not have lung cancer (false positive results).

In other words, out of 1,000 people screened, you save three, you hurt three, you kill one and 351, or 35 per cent, will suffer anxiety as they await a final “you don’t have lung cancer” diagnosis.

Out of 1,000 people screened, you save three, you hurt three, you kill one and 35 per cent will suffer anxiety as they await a final “you don’t have lung cancer” diagnosis.

Based on this mix of benefits and risks, the task force only weakly recommends LDCT lung-cancer screening for those at higher risk based on age and smoking history and strongly recommends against screening individuals who are not at higher risk.

“Being screened is an individual preference. Because of the small chance of benefit, and the risk of possible harms, you should discuss your decision with your primary-care provider,” the task force advises.

The 2021 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force LDCT recommendations were more supportive: “There is high certainty [grade B] that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial. … The USPSTF recommends annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) in adults aged 50 to 80 years who have a 20 pack-year smoking history (smoking the equivalent of one pack a day for 20 years) and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years.”

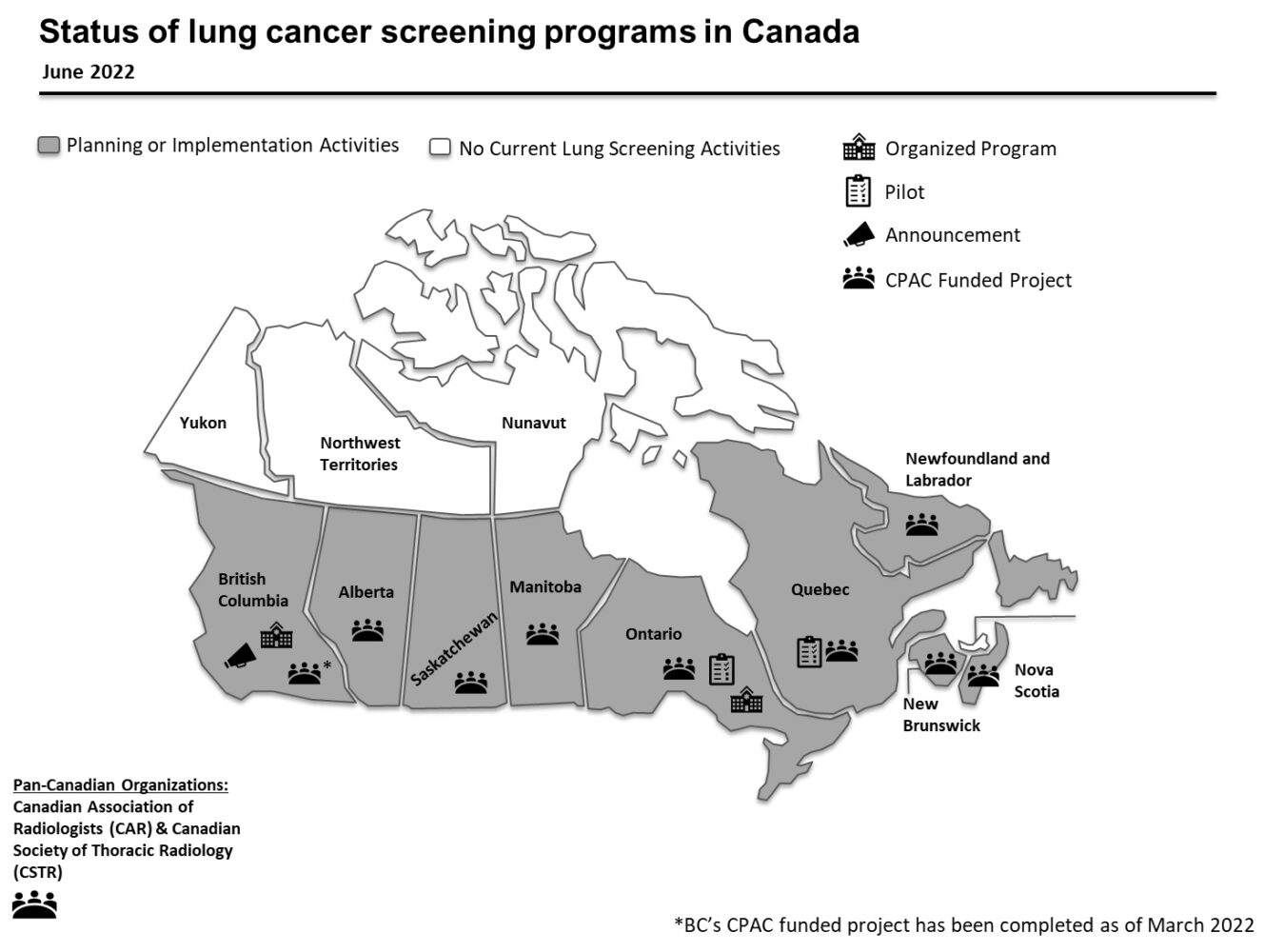

The figure below demonstrates LDCT lung-cancer screening activities across Canada as of 2022.

Unfortunately, Canadian LDCT lung-cancer screening programs are being rolled out as “opportunistic” screening programs lacking the structure and organization of established screening programs for breast, colon and cervical cancers.

“Opportunistic screening – where screening occurs in an uncontrolled and unmonitored environment – is already happening. Opportunistic screening is known to result in increased costs and negative impacts to individuals than would occur with organized screening designed to ensure the right people get the right screening test and follow-up at the right time,” according to the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer.

What is missing from this dialogue is: “About 86 per cent of lung-cancer cases are due to modifiable risk factors, making it one of the most preventable cancers in Canada,” says the Canadian Cancer Society. Smoking, second-hand smoke and radon gas account for most lung cancers.

With this in mind, continued strategies to reduce already declining smoking rates and ramping up radon surveillance mitigation measures in residential settings should be top priorities.

The benefits of preventive programs are borne out over long periods of time, decades in the case of smoking cessation. This makes them a less attractive policy option as they evolve over multiple election cycles, meaning politicians can’t cut a ribbon celebrating less lung cancer – but they can cut a ribbon on a new LDCT screening program, which is less effective. Go figure.

Back to my grand rounds audience. Those with green dots please stand up. Congratulations, because of the LDCT screening program, you have survived your lung cancer. Brown dots: Sorry, you are hospitalized due to complications of your lung biopsy procedure. Blue dots: Your LDCT scan was positive, but you will have to wait to find out that there is nothing to worry about. Ah, yes. Who has the black dot? My condolences, sir. You died from the complications of your lung biopsy, and not from lung cancer.

With odds like these, the decision to screen, or not, requires transparent, informed consent.

Source: Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, Power Point slide 5 – used with permission.

The comments section is closed.

Succinct and informative piece!

Can the editors f/u with perspectives on colon cancer screening and breast cancer screening?