With advertisements plastered everywhere from public transport vehicles to large billboards over highways and a proliferation of messages over social media, the buzz about GLP-1 receptor agonists is practically unavoidable. The catchy slogan “I just asked” may seem ambitious, but a recent surge of online platforms have streamlined the process of getting the drug to be akin to answering a survey.

The popularity of semaglutide, more commonly known as Ozempic, as a weight-loss drug rather than its original purpose of helping to manage Type 2 diabetes has created shortages for patients and raised ethical questions about its use.

While some of the blame for shortages should be placed on companies for controversial business tactics, most of it lies with a system and society rooted in weight bias.

A go-bus seen with an ad for Ozempic on the side within the GTA (credit: CBC)

A go-bus seen with an ad for Ozempic on the side within the GTA (credit: CBC)

The surge in demand has left diabetic patients who depend on it for control in a scramble. While the shortages are frustrating for individuals who rely on it for diabetes management, it’s crucial to acknowledge that this medication can be beneficial in addressing obesity, especially given the lack of other treatment options.

Guidelines suggest that those who have a BMI of 30+ or BMI between 27-30 with a weight-related condition such as high blood pressure qualify for Ozempic prescription. The criticism that those with obesity are “stealing” the medication from diabetics is flawed as it places societal value on which chronic non-communicable diseases are most important.

Rather, the issue is with online health-care platforms that exploit vulnerable patients who are eager to conform to societal weight biases but do not qualify for the drug or receive proper counselling.

A Toronto Star investigation outlined how easy it is to obtain Ozempic. With just a form submission, uploading a full-body photo and a few exchanges with a nurse practitioner, a reporter was quickly approved. What’s particularly alarming is that even after providing inaccurate weight information that didn’t align with the photo, approval was granted within minutes. After paying and receiving the medication by mail, the reporter did not hear from the company regarding follow-up, demonstrating the lack of thorough investigations and consultations for these medications, with the goal being financial gain, not patient care. This lack of accountability and regulatory oversight raises ethical concerns, especially when catering to individuals navigating complex health conditions requiring longitudinal comprehensive care, such as obesity and diabetes.

This ease of access must be carefully balanced with the quality of care being provided by these services. Inadequate comprehensive assessments and lack of discussion prior to initiating these medications increases the risk of poor outcomes. The nature of companies that offer these services as their main treatment modality introduces potential conflicts of interest. Financial conflicts of interest exist in many spheres of medicine today, but nonetheless should be considered.

Autonomy is a fundamental principle in medicine, encapsulating patient rights to make decisions about their health informed by their values, preferences and goals. However, it is not uncommon for patients to experience weight-related stigma and dismissal within health-care settings, resulting in loss of autonomy and barriers in obtaining appropriate treatments. The online platforms offering access to medications like Ozempic can empower patients to choose treatments aligned with their goals.

There are, however, valid concerns about the completeness of information and the level of informed decision-making facilitated by these platforms. Informed decision-making requires a thorough discussion of treatment options, including alternatives and potential risks, which may not be adequately addressed in the online consultation process. This raises doubts about the true extent of patient understanding when making the decision to start Ozempic via one of these platforms. If a decision is not made when fully informed, it is not autonomy but rather manipulation.

Many of these issues can be boiled down to living in a weight-biased society where stigma surrounding obesity is commonplace. As Yoni Freedhoff, an associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa and founder and medical director of the Bariatric Medical Institute, explained, these companies would not exist if our medical landscape effectively cared for patients with obesity. If doctors were appropriately trained and willing to learn how to properly manage these patients, these ethical issues would dissipate. These health-care platforms fill a much-needed niche and gap in care for patients who want treatment but cannot access it through traditional means. Freedhoff says it begins with problematic practices from doctors who are not willing or interested in learning how to prescribe and care for patients with obesity.

Online Ozempic prescription services are praised by some for dismantling diet culture and addressing the dangerous cycle of yo-yo dieting by diminishing food cravings. Those endorsing this view believe that Ozempic is a solution to obesity, even though individuals must remain on the weekly injection long-term.

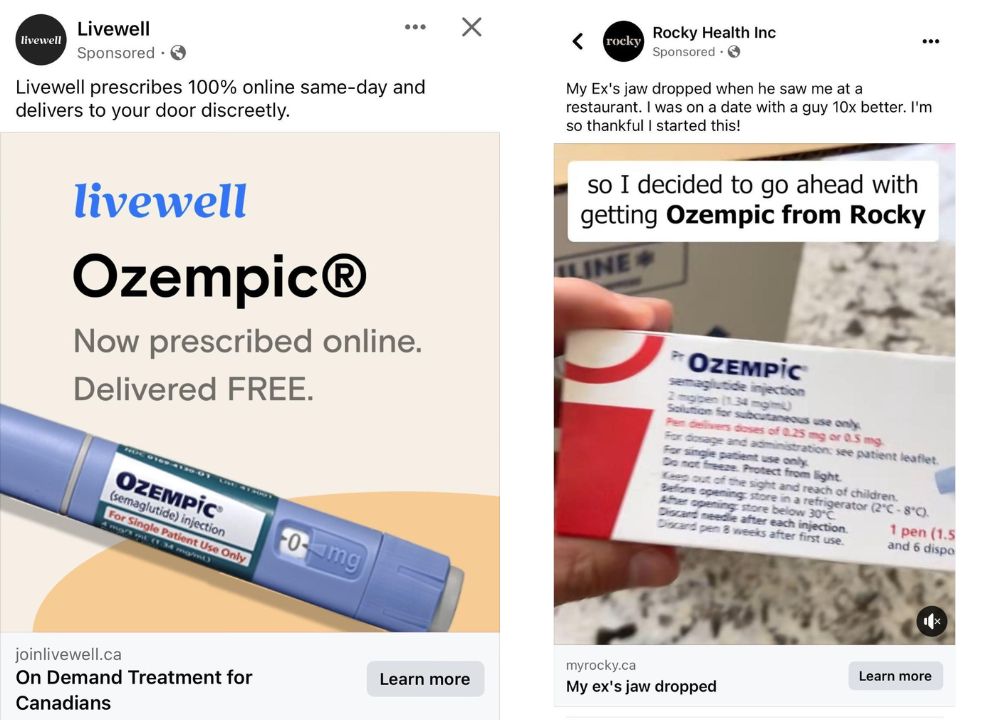

But there are also concerns that these services promote a weight-bias culture, where achieving a slim physique and weight loss is the primary goal, further perpetuating diet culture and weight stigma. This goal is evident through marketing that boasts quick and easy Ozempic access and often explicitly shames obesity. In addition, the absence of guidance on lifestyle modifications demonstrates that the primary focus is on weight reduction rather than promoting overall well-being.

Advertisements from popular online healthcare companies, Livewell and Rocky Health, promoting online same-day Ozempic prescription and delivery.

Advertisements from popular online healthcare companies, Livewell and Rocky Health, promoting online same-day Ozempic prescription and delivery.

Thus, patients with obesity are caught in the middle of two ethical issues rooted in weight bias – the reason the online services exist and the online services themselves. We have physicians who do not wish to prescribe Ozempic or shame obese patients and we have online companies who use marketing rooted in fat-shaming and exploit the weight stigma that is pervasive in our society. Furthermore, patients who do access Ozempic for obesity management are shamed by our society for “stealing” GLP-1 agonist medications from diabetic patients.

Moving forward, instead of blaming patients, we must work on dismantling a system that is deeply rooted in weight-bias to resolve these ethical concerns.