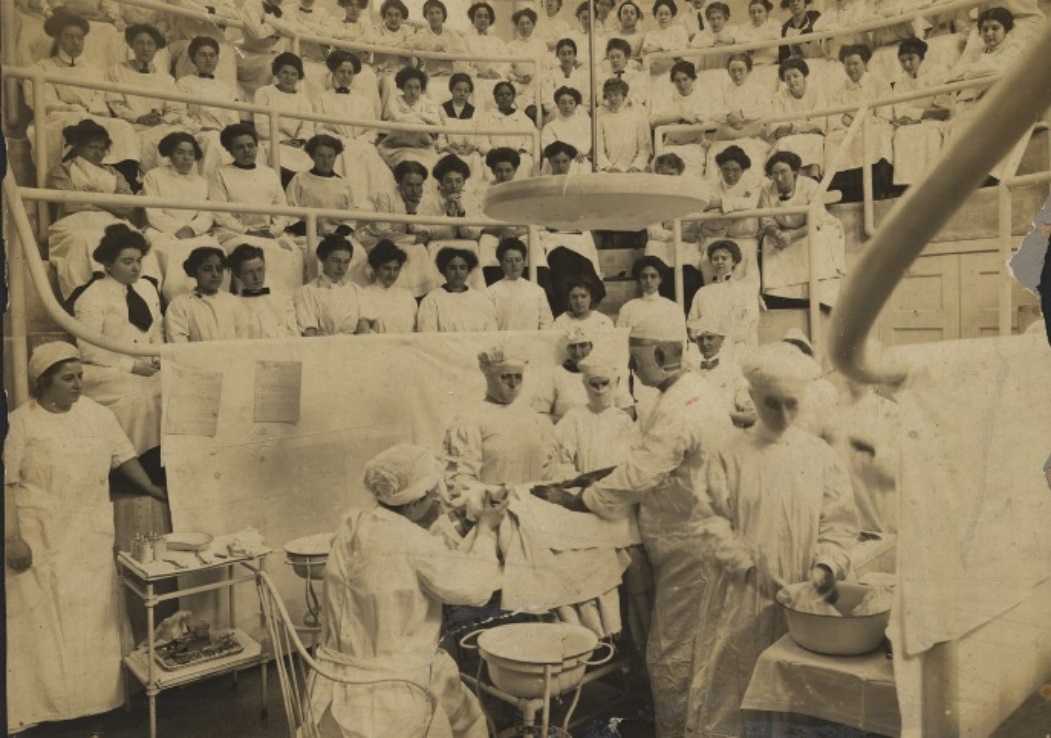

Students at Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1895

“The doors of the University are not open to women, and I trust they never will be,” said the Vice-Principal of the Toronto School of Medicine in 1865 to Emily Stowe. She replied, “Then I will make it the business of my life to see that they will be opened, that women will have the same opportunities as men.”

Stowe earned her medical degree in the United States two years after this rejection and returned to Canada in 1867 to become its first female physician, although she worked out of her Toronto clinic without a formal medical licence until 1880.

In 1871, Stowe and her younger contemporary Jennie Trout were granted permission to attend one year of classes at the Toronto School of Medicine. Male students and professors heaped abuse on them, leaving body parts and garbage on their seats, painting misogynistic graffiti on the walls of the lecture hall and jeering openly at them during class.

Both women persisted, but only Trout sat for the qualifying exam in 1872. She passed but no Canadian medical school would admit her for further training, so she left to earn her medical degree in the United States. Upon returning home three years later, Trout was certified by the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario, becoming the first woman officially licenced to practice in Canada. The date of her licensure, March 11, 1875, is commemorated by Canadian Women Physicians Day, a date fortuitously close to March 8, International Women’s Day.

The story of Trout’s life and career illustrates much about the history of medicine, not only its foundational misogyny but its evolution through the social changes of the 19th century into the modern era. So can the life of one of Trout’s contemporaries, Sophia B. Jones, who couldn’t find a place within the sexism and racism of Victorian-era Canadian medicine.

Through them we can glean much about the underlying culture of the profession that echoes through to today, when women still lag in terms of leadership roles and income equality but soon will dominate in numbers.

Jennie Trout

Jennie Trout was born in Scotland in 1841 and moved with her family to Stratford, Ont., at age 6. She worked as a teacher before marrying in 1865 and moving to Toronto. Shortly afterward, she fell sick with a mysterious condition labelled “nervous disorder,” a catch-all phrase often applied to illnesses affecting women. Women’s health was of little importance to the 19th century medical establishment, so fringe or “irregular” therapies were common.

Trout learned from a friend about electrotherapy, which used the newly developed technology of electricity to stimulate muscles. She found some relief through galvanic bath therapy, which placed the patient’s extremities in water basins and applied mild electrical currents. This inspired Trout to seek a medical degree so she could offer galvanic therapy to other women, seeking to correct the misogynistic systemic inequity she had identified through her own experience with chronic illness.

Galvanic bath therapy

Many Canadian female physicians of the 19th century earned their degrees at American medical schools, often at institutions that emphasized “irregular” therapies because they were generally less competitive and had a greater willingness to explore new-fangled ideas like educating women. So it was that Stowe received her medical degree from the homeopathic New York Medical College for Women in 1867, and Trout’s medical education took place at Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, which offered courses in electrotherapy.

Students at Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1915

Trout’s work was deeply tied to her identity as a Christian in the Restoration Movement, and this was a throughline from her medical school days into the later stages of her life which focused on missionary work and temperance activism.

Medical education for women in this period was often associated with Christian missionary work, since a medical career as a “calling from God” provided moral justification for the gender deviance of pursuing an academic profession. As well, some of the only opportunities for female physicians were through missionary work abroad or in the less settler-occupied regions of North America.

Female missionary-doctors found they could be more authoritative in “uncivilized” settings and flourish professionally when away from male gatekeeping. They leveraged their positions within a colonialist and white supremacist framework to gain access to medical power.

American missionary physician in India, 1906

Sophia B. Jones is another 19th century woman who left Canada for an education in the United States, illustrating the climate of the time. Born in Chatham, Ont., in 1857 and raised by Black abolitionists who valued higher learning, Jones gained admission to the University of Toronto in 1879 as an undergraduate. However, no medical school in Canada would admit her, so the following year, Jones entered the University of Michigan’s medical school (which had an attached homeopathic school, although Jones didn’t attend it), becoming its first Black female medical graduate in 1885. Jones never returned to Canada, the combination of her Blackness and femaleness proving too great a barrier to practicing in the country of her birth. And while Canada’s first Black physician, a man named Anderson Abbott, graduated from the Toronto School of Medicine in 1861, enrollment of racialized minorities would be restricted by both official and unofficial quotas in Canadian medical schools until the 1990s.

Sophia B. Jones

Though leaving Canada to seek medical education in the U.S. was common for female doctors in the late 19th century, it’s worth noting who was able to return to practice medicine and who wasn’t. Physicians like Stowe and Trout are celebrated figures in Canadian history, lauded for their contributions to medical education and women’s liberation, while Jones is little known, despite having had her own remarkable career in medical education as well as public health. As the first Black faculty member at Spelman College in Atlanta, Jones taught at the school’s nursing college, establishing educational standards for a role with a long tradition in health care but which had not yet been professionalized.

We love our stories of Canadians who achieve American success, yet in Jones’ case, she is barely a blip in our histories, especially compared to her white contemporaries.

Spelman College nurses, 1897

Jones was a pioneer in public health, particularly regarding the African American community. She became one of the first Black women to publish a medical research article in 1913, entitled Fifty Years of Negro Public Health, which countered the prevailing view of inherent biological inferiority and called for improvements in education to counter disparities in health outcomes. Indeed, we see the relevance of her words today, over a century later: “Now another battle cry is sounding louder and more insistent: it is the battle cry of physiological teaching directed towards the prolongation of life and the diminution of human suffering, for without sound health, the finest classical education and the most useful industrial training avail nothing. The battle is being fought with united armies on a territory where all may operate – the field of public health.”

The nascent discipline of public health at the turn of the 20th century was another career path that provided opportunities for women that the more traditional structures of health care lacked. Many nurses enjoyed the autonomy of public health work and found it an escape from the more rigid, gendered role of doctor’s helper in the hospital setting. And much like with missionary work, female physicians saw a professional opening in a field that was less popular among their male colleagues.

The philosophy of public health dovetailed two major concerns of the late 19th century: the unhealthy environment of poverty-stricken slums and the push for women to have greater involvement in public life. The older tradition of wealthy women doing charity work for impoverished communities evolved into educated Victorian women at the forefront of social and health reform movements like child labour, sanitation, unionizing, maternal and infant health, vaccination and contraception.

Women’s liberation at the time centred on the ideology of maternalism, the notion that women had unique skills and feminine traits that could improve society by balancing the harms caused by men. This is why many of the earliest public health pioneers were women – their work was seen as a natural extension of the innate maternal drive to care for society’s most vulnerable.

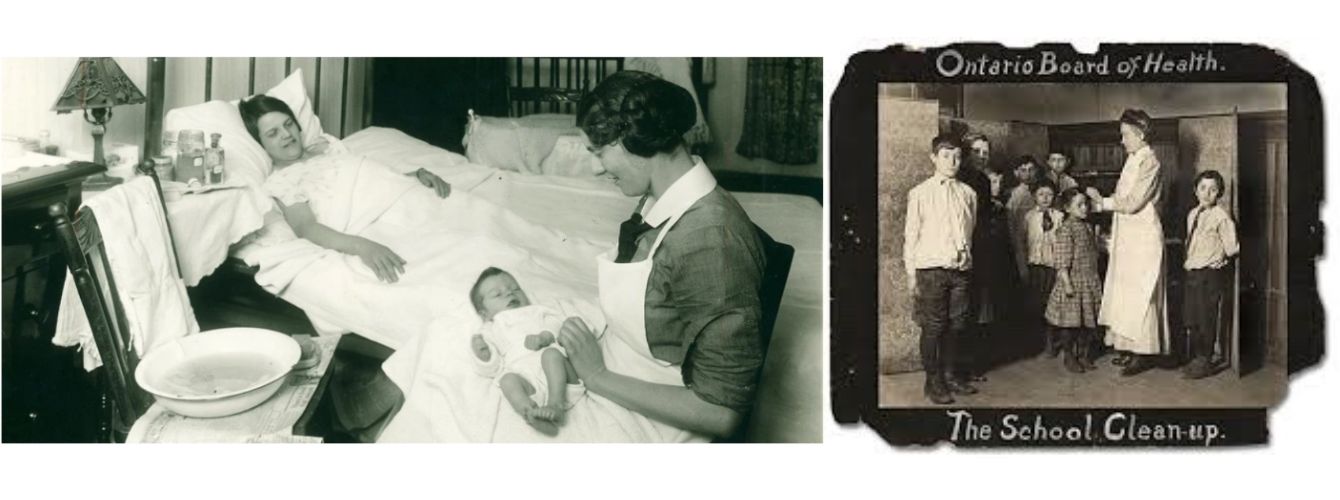

Turn of the century Canadian public health nurses, in the home and at school

Turn of the century Canadian public health nurses, in the home and at school

Trout was a staunch advocate for women’s medical education, playing a key role after her illness forced her to retire from practicing at age 41. “I hope to live to see the day when each larger town (at least) in Ont. will have one good true lady physician working in His name,” she wrote in 1881, demonstrating both the maternalistic philosophy and Christian missionary views that defined her time. During her short career as a practicing physician in the 1870s, she opened a free dispensary in Toronto, a departure from Victorian-era attitudes towards poverty but an act that would presage the development of Canadian Medicare nearly a century later.

For her part, Jones advanced the emerging understanding of social determinants of health, writing in 1913 that “between the columns of figures setting forth a large death rate from tuberculosis, one may detect the tragedy of human tribute paid for the maintenance of city slums and alleys, for ignorance and poverty.”

The careers of these remarkable physicians hit many relevant themes in modern Canadian medicine: inequitable care for women, the push for inclusion, limited paths for female physicians and the racial and colonial dynamics underlying it all. Women no longer face the struggles Trout and Jones did in gaining admission to medical school, but gendered ideas about the type of medical work women should do persist, as does racist discrimination at all levels of the health-care system.

By studying the history of this profession, we can better direct its future evolution, aiming for greater equity and opportunity as well as better health outcomes for all.