On any given day, I can convince people to do some rather bizarre things. I’ve persuaded a teacher to take a nausea-inducing pill, encouraged a construction worker to miss several paycheques, and even swayed a lawyer to cancel a bucket-list trip mere weeks before departure. This influence comes down to two letters stamped after my surname; letters that separately hold no meaning but together, confer a staggering amount of authority to their bearer:

M.D. Medical doctor.

From the days of the ancient Egyptian physician Imhotep, worshipped as a demigod for his clinical prowess, doctors have enjoyed a unique level of power. Most physicians wield this perception carefully, using their influence to inform and treat patients, but what happens when this authority bleeds out from hospitals and into social media?

Enter the physician influencer. Scrolling through the #medicine tag online reveals countless Canadian doctors and medical students providing a behind-the-scenes peek into life in medicine. Some physicians use their accounts to disseminate medical knowledge. Others raise awareness of inequity in medicine. There are even those who share their non-medical passions for things like stand-up comedy and painting.

Still others, however, have leaned into the niche of lifestyle influencing, sharing carefully curated highlight reel of their fascinating medical careers inside the hospital and their fabulous lives outside it. It is aspirational lifestyle content geared toward members of the public who are eager to get an inside scoop into this previously secrecy-shrouded profession.

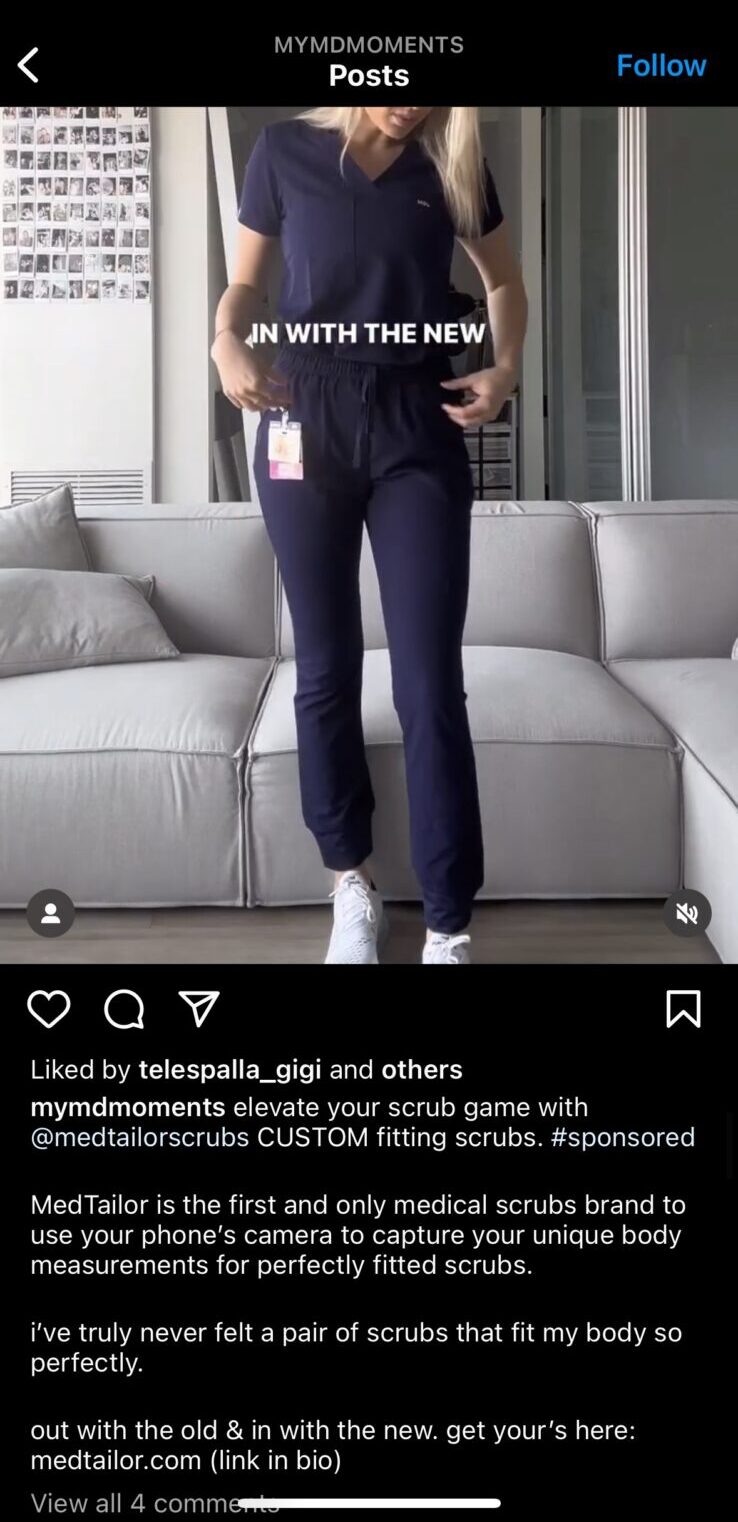

Justina Melkis, known online as @mymdmoments, is one such med-fluencer who has documented her experience through medical school and gained an enraptured audience. A soon-to-be graduate from the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Medicine, she started her account “to provide supports and insights into the world of medicine,” as she describes in a recent video posted on Instagram.

She uses her platform to help aspiring doctors by discussing strategies for writing medical college admissions tests and interview preparation tips. She works hard, with many videos documenting gruelling days in hospital and laboriously long study sessions. But she also plays hard, demonstrated by the intense gym sessions, fashion content and international travels interspersed between medical content.

This formula has paid off, with Melkis garnering 60,000 followers on TikTok and almost 9,000 on Instagram. Once an audience of this size is established, the next step is to monetize the account through sponsored content. Her account shared promoted content for companies like DiagnosUs and Pyrls, clinical study apps targeted towards health profession students.

But her sponsorships also include products that appeal to her non-medical followers. The collaborations section of her Instagram account shows partnerships with CBD gummy companies, Women’s Best vegan protein powder, SmartSweets, WakeWater caffeinated sparkling water and a variety of skincare companies. It seems just like the fitness Instagrammer or the TikTok makeup artist who promotes products to their followers.

There is one crucial difference, though. People take a doctor’s recommendation a lot more seriously.

It is one of the benefits that comes after years of schooling and the conferring of a medical degree. A study published in Social Science & Medicine found that even today, the public views doctors as “godlike” due to their perceived intelligence and capacity, much like our ancient Egyptian colleagues. It is reasonable to utilize that perception to advise patients on the topics we are experts in, but is it right to use it to make money?

I interviewed Melkis about her start on social media and her experience with brand collaborations, but for medical students like Melkis, there are no official guidelines for posting sponsored content, and some use it to raise funds during their student years

For physicians, however, it is an entirely different story.

The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO), the regulatory board for the province’s doctors, has a clear stance on the matter. When asked for a comment on the ethics of physicians using their influence to promote products online, the CPSO directed me to its advertising policy, which states that “physicians must not permit their name or likeness to be used in or associated with advertising for any commercial product or service other than their own medical services.” The college did not elaborate on the specific applications of the policy to physician social media influencers, though it must be as evident to the college as it is to me that there is a stark difference between a fitness influencer promoting a protein supplement versus a doctor doing so.

It is reasonable to utilize that perception to advise patients on the topics we are experts in, but is it right to use it to make money?

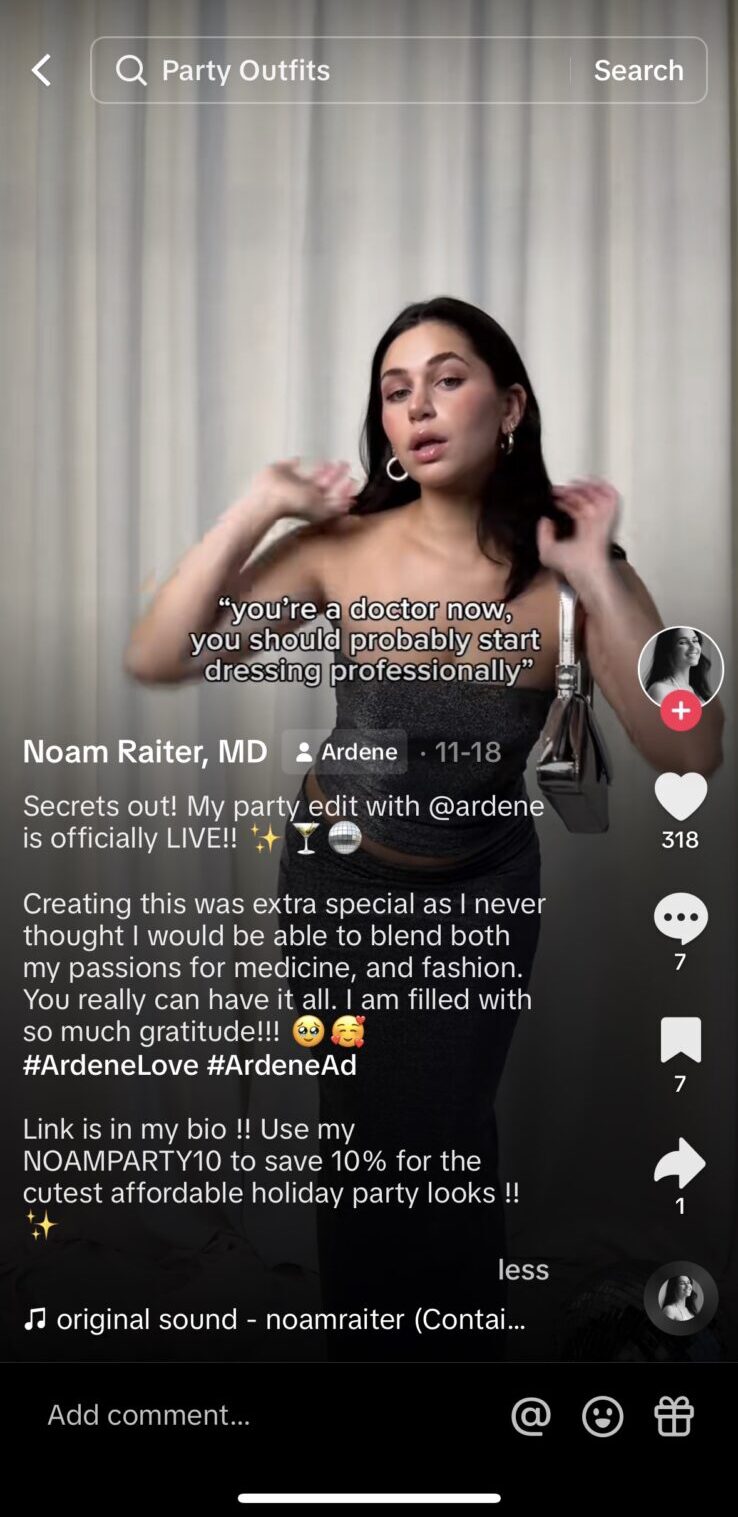

The policy seems to forbid any form of income from social media advertisements, but it has not stopped doctors from proceeding with sponsored collaborations. Noam Raiter, a Toronto family medicine resident doctor with more than 100,000 Instagram followers, is one such physician.

It is hard to distinguish where the physician ends and the influencer begins in Raiter’s content. She leverages her identity as a physician while promoting a collaboration with Canadian fast-fashion company Ardene, modelling clothing under the tongue-in-cheek caption “you’re a doctor now, you should probably start dressing professionally.” Similarly, she has shared a promotional video in which she attributes her productivity and success to the use of various Samsung Galaxy devices.

In a more dubious sponsored video, Raiter shares that she focuses on her gut health by consuming Activia probiotic yogurt products. The nebulous term “gut health” could be interpreted in any number of ways, from benign conditions like bloating to serious diseases such as ulcerative colitis that cannot be managed by eating yogurt. There is no mention that research on the efficacy of probiotics is equivocal, with no evidence that Activia helps with irregularity, bloating or gas symptoms. She does not explain why she promotes Activia specifically instead of several other probiotic brands available on the market.

Industry standards suggest that accounts with similar audience sizes to Raiter’s rake in six figures annually. This can be a massive financial conflict of interest, arguably on par with that of Big Pharma paying doctors to prescribe their brand of medication, a practice that is taught as unethical to all doctors. I spoke with Raiter for this story; she ended the interview when I asked about her collaboration with Activia.

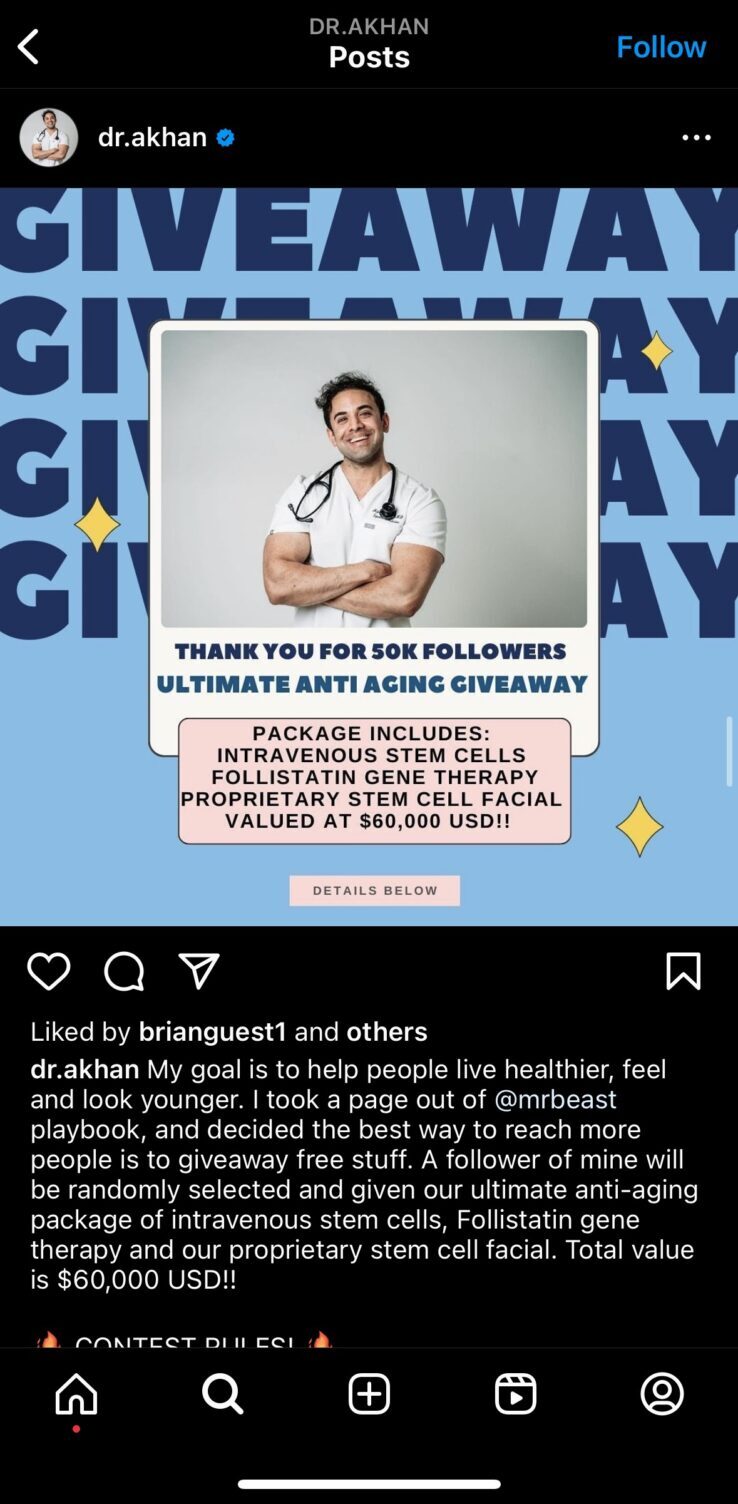

The CPSO does permit physicians to advertise their own medical services, but there are equally questionable practices within this category of social media influencing. Adeel Khan is a Toronto family physician with 75,000 Instagram followers who describes himself as a “regenerative medicine doc” in his biography, a medical specialty that is not recognized by any medical governing board in Canada.

He does not share sponsored content, but rather promotes his use of stem cells for the treatment of everything from musculoskeletal conditions to chronic pain, kidney disease, psychiatric conditions and even penis enlargement. There is no obvious acknowledgement on his account that there is minimal evidence supporting stem cell use for any of these conditions.

He has posted a giveaway for a stem cell anti-aging package to celebrate reaching 50,000 followers, directly violating the CPSO guideline to avoid “offering medical treatments as prizes in contests.” He shares extraordinary before-and-after photos of stem cells promising copious hair growth and bodybuilder-level muscle gain. He even posts his own anti-aging regime, comprised of treatments he provides, that he claims should help him live to 150 years old.

These procedures are not covered by OHIP, and a prospective patient would need to pay out-of-pocket. Furthermore, the treatments he advertises are not approved by Health Canada; his clinic circumvents this by offering luxury medical vacation packages in Dubai, Mexico and Japan. I could not find an estimate of the cost of these packages anywhere online, although I assume the provision of experimental treatments at international five-star resorts does not come cheap. Khan was unavailable for comment for this article as he was treating patients in Los Cabos at the time.

Khan is certainly not alone when it comes to dubious self-promotion on social media. It is a trend that seems to have been started by cosmetic doctors, another group of physicians that rely on convincing patients to spend money on their services. A notorious example is that of Martin Jugenburg, a Toronto cosmetic plastic surgeon who was suspended by the CPSO in part for sharing inappropriate social media posts to his 140,000 Instagram followers.

There are ways for physicians to make money online that do not rely on lending medical authority to experimental interventions or commercial products. Violin MD, also known as Siobhan Deshauer, is a Canadian rheumatologist and Youtuber with almost one million subscribers, posting educational videos about rare medical cases and patient experience interviews. It is an arduous process that requires intensive research and fact checking before posting content online.

Her account generates income through advertisements that play before her videos. She has no control over what adverts are shown; rather, they are selected by a Google algorithm that personalizes the ads to the individual viewer based on demographics and previously viewed videos. “I’m grateful to get some ad revenue to help offset the costs of editing,” she says.

Deshauer has collaborated with two organizations during her time on YouTube, the Canadian Blood Services and the Doobay-Gafoor Medical & Research Centre Inc., a clinic in Guyana that relies on the volunteer services of Canadian physicians. She chose to work with them to bring awareness to the important services they provide. She receives countless emails every day with offers to advertise both medical and non-medical products, offers that she has not taken up as “maintaining trust with the public is very important,” she says.

It is important to note that high-profile, high-income physician social media accounts are few and far between in Canada. Most doctors on my feed use social media to democratize access to health information or to amplify causes that they are passionate about and make no money in the process.

Stephanie Zhou is an Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto Temerty Faculty of Medicine and creator of the financial literacy curriculum. She taught herself personal finance to pay for medical school and found that her knowledge was invaluable to students from low-income households who wanted to keep their debt burden down.

Under the handle @breakingbaddebt on Instagram and YouTube, she describes herself as a “knowledge translator” who makes complex topics simple, with subjects ranging from budgeting to mortgages to the First Home Savings Account. What initially started as an account for medical students has now ballooned to viewers from across the world and specifically, new immigrants to Canada who often struggle with navigating the jargon of the Canada Revenue Agency website.

“I don’t try to sell people stuff,” she says, even though she has had ample opportunity to monetize her account. Fundamentally, she says, her online role as a financial educator is an extension of her work as a doctor. “A lot of what I see in clinic is not always medical, a lot of it is financial,” she says. “They’re coming to me for advocacy.”

Another physician using social media as a platform is Naheed Dosani, a palliative care doctor and self-described “health justice advocate” with 90,000 followers on X, the website formerly known as Twitter. He is a fierce advocate for patients who are often overlooked by the health-care system, such as those experiencing poverty and homelessness. His followers are not only medical professionals, but “people with lived experiences of poverty and homelessness, who follow me, who are curious about what I say, as I’m often advocating for them as a group,” he says. “When I first created my accounts, the real focus was to bring light to the immense suffering that occurs when people do not have homes.”

This online advocacy has had real life effects through the creation of the Palliative Education and Care for the Homeless (PEACH) program, an innovative mobile care team that provides end-of-life care to patients “in the community, on the streets and in shelters.” The program has an immense amount of public support that he says “is a reflection of the public-facing advocacy that many of our PEACH team members engage in.”

Clearly there are different ways for doctors to use social media, all of which hinge on the additional authority that a medical degree provides. I contacted several physician ethicists to hear their thoughts on the phenomenon, but I received no responses. I wonder if, in a field that still relies on fax machines as a primary mode of communication, our ethicists have not yet considered the concerns surrounding physician social media use.

What I do know is that the amount of authority my medical degree gives me can be overwhelming. This authority is what I rely on when recommending a patient spend $250 on a meningitis vaccine, or shell out three grand for an ADHD assessment. These are massive sums of money for most people that they spend anyway because of the trust placed in my suggestions. Physicians must balance on this precarious line, teetering between recommending a valuable medical intervention and placing a significant financial burden on a patient.

It is evident that many Canadian physicians apply this same clinical rigorousness to their online presence and, in doing so, are bringing our profession into the modern world. It is also evident that we need to regulate how we present ourselves online, particularly in the sphere of sponsored content. We could turn to our regulatory bodies for clearer guidance or to our workplaces for better policies. My suggestion? Perhaps we should remind ourselves of the most fundamental principles of our profession: first, do no harm.

I don’t trust any doctor who is enforcing products online or those who insist you keep taking a medication that has side effects. I nearly had kidney failure from certain cholesterol pills. I no longer have that Doctor.